Section Branding

Header Content

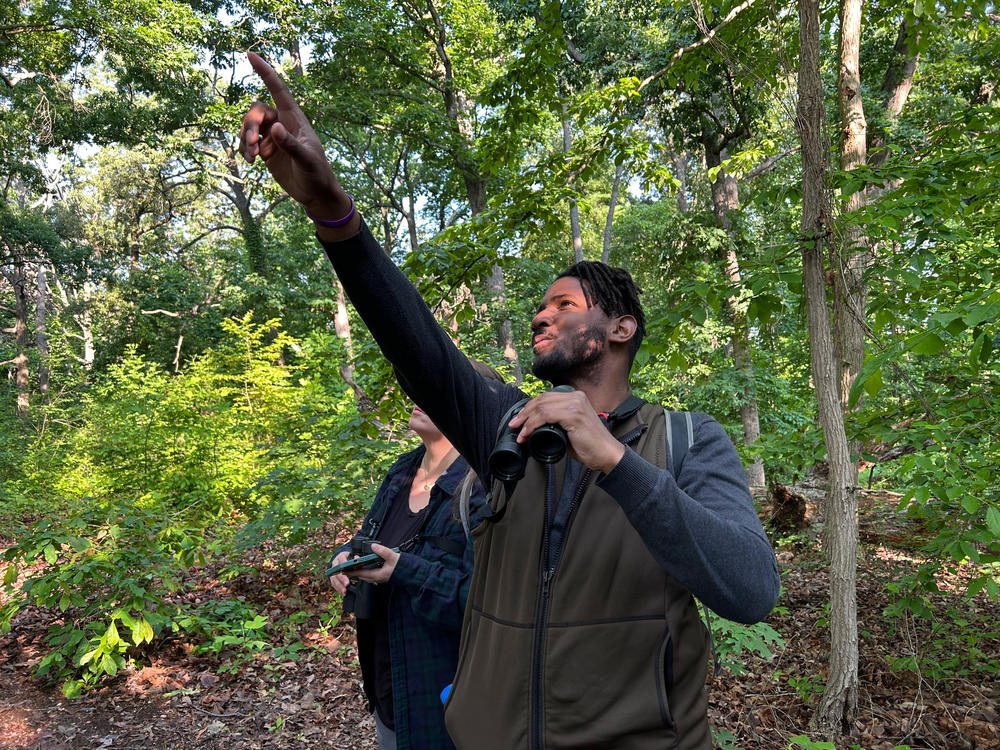

Heads up! Stunning birds are all around us, even in dense cities

Primary Content

This time of year, there are a lot of seasonal visitors to our nation's capital — the avian kind, that is. Washington, D.C., is rated as having the nation's best city park system, and migratory birds flock here on their journey north, many of them having traveled thousands of miles to nest and breed.

Early on a Sunday morning, I meet up with a few fellow birders to catch the tail end of spring migration. We gather in Fort Slocum Park, which formed part of the city's defenses in the Civil War. Just a few blocks long, it's set among brick rowhouses in the heart of D.C. But step into the park, up a slight hill, and the city quickly vanishes; you find yourself under a thick canopy of towering oaks and elms.

Tykee James, the president of the DC Audubon Society, comes here often. "Pros and cons of being in here," James says, "it's very dense, so it's really great migratory stopover habitat. But –"

He pauses, detecting the high sweet song of an eastern wood-pewee. "Oh! 'peweeeeee,' " he sings along. "Nice. But yeah, you're going to hear more than you see."

That little eastern wood-pewee has likely migrated all the way up from South America to breed.

"'Peweeeeee!' Once you hear it, you can't unhear it," says our fellow birder, Emmie Bhagratti, who works for a federal agency and is a bird guide for DC Audubon. "People think when you're birding in a big city, you can't get to places like this," she says, gazing up at the dense green canopy. "But honestly, with the exception of some ambient noise, I mean, would you know that you're in D.C. right now? This is just a beautiful, beautiful spot."

In the early morning sun, the birds are stirring into song. We hear the buzz of a blue-gray gnatcatcher, the burbly "cheerio" of red-eyed vireos, and the insistent "teakettle, teakettle" song of the Carolina wren. "One of the smallest birds, but also one of the loudest!" Bhagratti says with a laugh. "It's a loud bird, singing with all of its might!"

Pretty soon, we hear the raucous rasp of a great crested flycatcher, and we find the bird perched on a nearby branch: It has a sporty grey crest and a pale yellow belly.

Erin Connelly, an environmental educator for a local nonprofit, has joined us with her 10-month-old son, Louis, strapped to her front. She spots two male eastern towhees deep in the underbrush. "Really beautiful bird," she says. The male towhee is black on top, with a white belly, burnt-orange sides and white patches along the wings and tail. Their trilling song sounds like a polite command: "Drink your teaaaaa!"

Suddenly, we hear an excited "Oh! oh! oh!" from our birding companion Jo Stiles. As luck would have it, she's spotted one of my all-time favorite birds: a spectacular male American redstart. He's jet black, with stunning, bright orange patches on his sides, wings and tail that flash in the sun. Despite the redstart's name, "it's not red to me at all," says Bhagratti. "It's very much like a Halloween orange and black palette."

Birders will often talk about their "spark" bird — the one that first got them hooked. For James, it was a belted kingfisher: specifically, a female he saw flying across a creek, displaying the chestnut-colored "belt" across her belly and calling out with the bird's trademark noisy rattle. "That call is in my head! It's very loud," he says approvingly. "Has a nice mohawk crest situation, pretty sizeable beak."

Stiles, who works on Capitol Hill for her hometown congressman, is especially fond of loons. She grew up hearing loons on summer trips to Lake George in New York's Adirondacks, and she and her sisters learned how to imitate the loon call from their mother and grandmother. "It's a very melancholy call, which is very beautiful," she says. To demonstrate, she cups her hands to her mouth, and a convincingly mournful loon call echoes through the woods.

So convincing, in fact, that it fools the Merlin bird app, which identifies the audio of bird songs and calls. Merlin "hears" Stiles's call and reports that there's a loon nearby.

James looks at the app on his phone and laughs: "It came up as a loon!"

"No way!" Stiles says. "That's awesome!"

In the end, after about an hour and a half in the park, we've seen or heard 23 species in all, loon excluded. Not bad for a morning's amble in the heart of Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.