Section Branding

Header Content

Incarcerated teens find escape in music and poems composed with artists

Primary Content

Jaylene is about to turn 16. But it's no Sweet Sixteen. She's among the tens of thousands of kids who wake up each morning incarcerated across the United States.

One thing's clear for Jaylene: she wants to break a cycle that she says also landed her uncles and her physically-abusive, alcoholic father in jail. She's due to get out in September after being booked for a drug-fueled, high-speed car chase and two hit-and-runs. It was her first time behind the wheel, she says.

Music, she says, gives her hope for a better life. "At the time of my arrest, I was very heavy on percs [percocet] and fentanyl. And my withdrawals would make me become a person that I'm not, make the evil come out of me," Jaylene tells NPR's Morning Edition host Michel Martin. "Music is my escape, you know? That's my therapy right there."

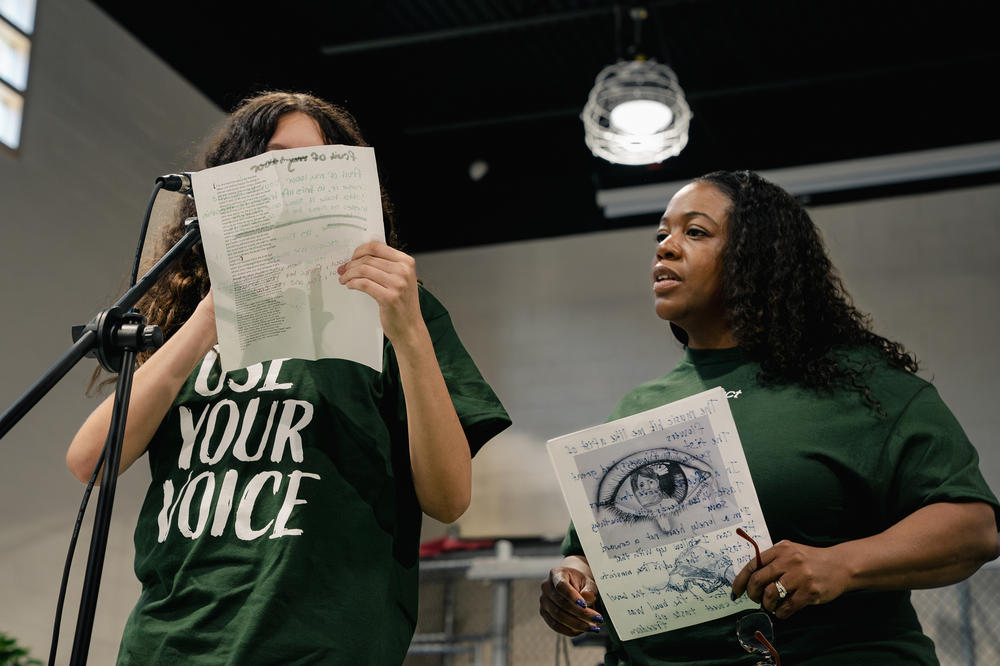

She performed spoken word as part of a group of 12 kids at the Northern Virginia Juvenile Detention Center for a recent three-day workshop to write poems, compose melodies and play with six musicians from the Sound Impact collective. A larger group of 30 teens listened to concerts on the first day. NPR is only using their first names for privacy and security reasons.

"The system looks at us as animals," Jaylene says. "But I appreciate people taking the time to come in and work with us because they know we got potential. At the end of the day, we're still kids, you know, and a kid is going to be a kid forever, no matter what."

Jaylene, who says she loves rap and cites J. Cole, Nas and Lil Baby as inspirations, read the following original text: "Fruit of my labor, about to go and chase it. / In this life there's no escaping / about to take it slow and patient. / There's no need to go and waste it. / It's basic, just face it. / There's no escaping the matrix."

Joint performances saw the young detainees read spoken word and poetry or play simple melodies accompanied by the musicians on a makeshift stage of artificial turf. Sometimes, the musicians would stand or crouch near the kids wherever they sit or lay on cushions, surrounded by potted plants.

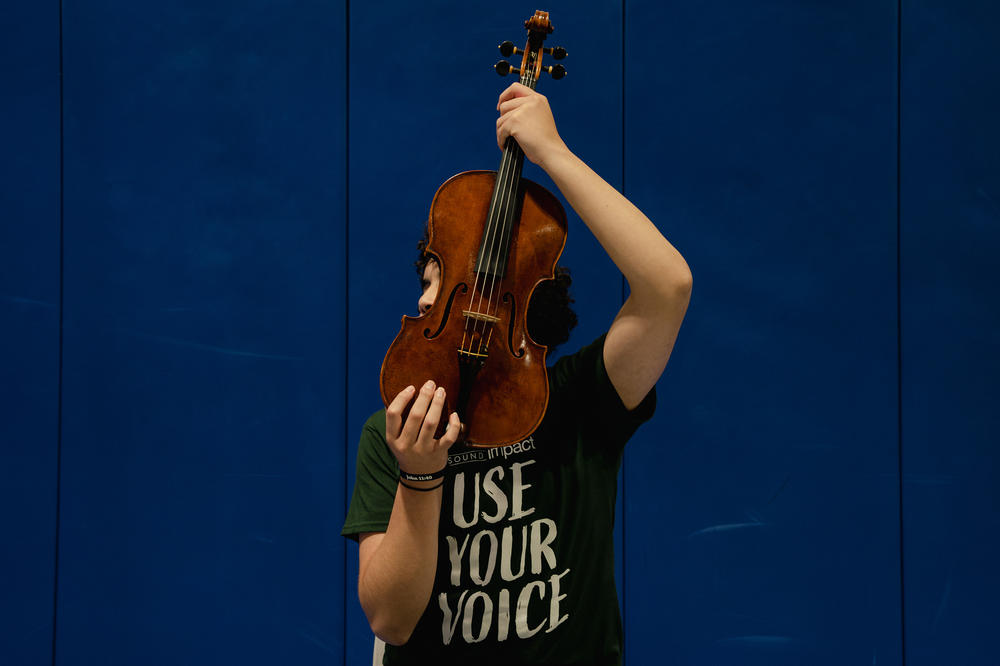

Large posters of colorful, bucolic scenes - bursting with waterfalls and blooming rhododendrons - hung around the gym with plastic tile flooring. In a final performance, the musicians — a violist, cellist, flutist, trumpeter and two violinists — performed "Turn-Around." Composer James M. Stephenson stitched together the piece based on short melodies the youths wrote on the first day of the residency.

"Music makes you okay to feel whatever way you're feeling," says Keisha Johnstone, a member of Sound Impact's board who advocates for at-risk youth. She says interacting with the musicians and participating in the creating process helps these kids build self-confidence and self-worth to work through and overcome their past missteps and trauma.

"When they wrote that song and our musicians came behind them and started playing, they were like, I can write, I can produce," Johnstone adds. "All you got to do is start planting the seed... and eventually they start to see."

Another incarcerated young person, Aunner, shares a poem that begins with: "Awake, awake / cast away the darkness / which fills deep within / you are light, you shine the void."

He says his poem is about finding light during a "very dark" time after he used drugs and got kicked out of his home by his mother. "As a young man, society tells you don't cry and stuff like that. But it's okay to let those emotions go. It's better to let it out."

Aunner's grandfather was a fiddler, a connection to music that has endured. "When the song is right, you get goosebumps and all that stuff is very beautiful, very beautiful music," he says.

Now, Aunner says he's aiming to share his experiences with drug use because "I don't want nobody to go through what I had to go through... it's just not worth it."

Jail is a hard place to grow up. Federal data estimates the number of jailed young people at around 25,000, while the American Civil Liberties Union says there could be as many as 60,000.

"I just want to enjoy being a kid," Jaylene says. "Yeah, we're locked up. But also we're building family, we're building strength and we're building a child in here as well."

The radio version of this story was produced by Ben Abrams. The digital version was edited by Phil Harrell.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.