Section Branding

Header Content

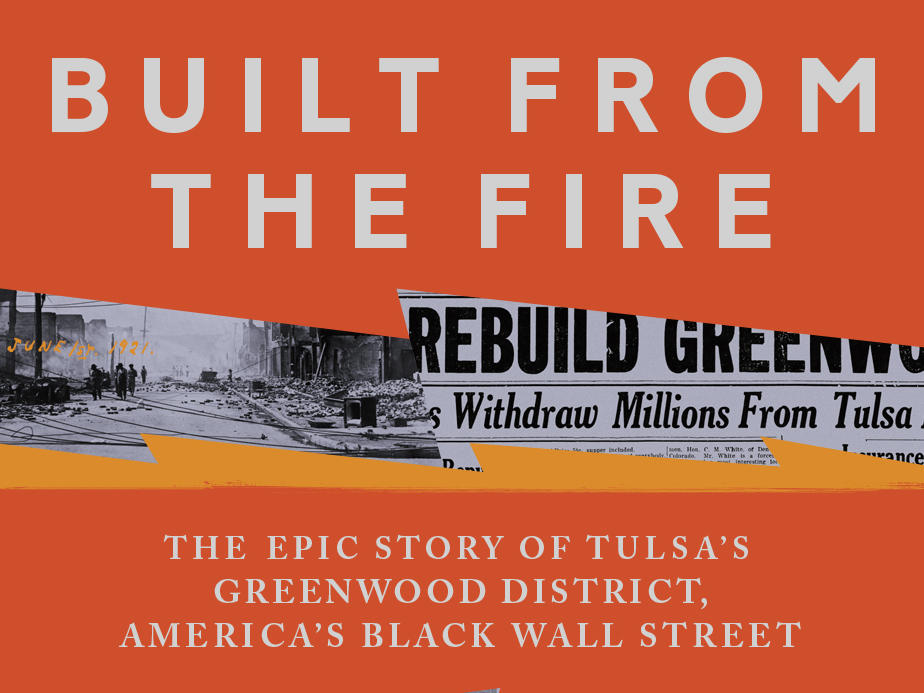

The Tulsa Race Massacre is recounted through family memories in 'Built from the Fire'

Primary Content

One of the most horrifying episodes in American history spanned just two days in 1921, when at least 300 people were killed on May 31 and June 1.

The attack by a white mob on African Americans in Greenwood became known as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

While documentaries have told the story of what transpired, a new book by the journalist and author Victor Luckerson focuses on the descendants of survivors.

"Too often, the Tulsa Race Massacre is reduced to statistics: 1,256 homes destroyed, 35 square blocks burned," Luckerson told NPR. "But this is really a story about people."

One person hid in the bathtub, another waved away rioters on the porch

In "Built from the Fire," Luckerson tells the story of Greenwood largely through the eyes of the Goodwin family.

Regina Goodwin currently represents the Greenwood district in Oklahoma's statehouse. Her ties to Tulsa go back generations, and her family was shaken by fear when the mob attacked what was often called the "Black Wall Street" more than 100 years ago.

Her grandfather and aunt were graduating from high school, Goodwin told NPR's Michel Martin.

"And they were in a play that night of the massacre," she said. "They heard that trouble was coming. They were able to leave that site and get to safety."

Her grandfather hid in a bathtub in their house.

Her great-grandfather went outside to save his family, his home and himself.

"He looked like a white man. He stood on the porch of his own house and waved the mob away," she said. "And they thought he was a white man. They weren't burning down white homes. They were just burning down Black folks' stuff."

'We don't know what Greenwood would have become'

Goodwin's great-grandfather was self-made businessman James Henri Goodwin, who had moved his family from Jim Crow Mississippi to Tulsa in 1914 and who went by "J.H.".

Despite racial segregation, opportunities in Greenwood appeared limitless, and J.H.owned a real estate office, a funeral home and a grocery store. He expected his offspring to continue his entrepreneurship, and after the massacring mob destroyed businesses and burned down houses his family sought restitution.

"We don't know what Greenwood would have become if not for the massacre," Luckerson said. "We don't know what would have become of the Stradford Hotel, the Dreamland Theatre, the Tulsa Star. But it is a blessing that we had families like the Goodwins who stayed and did rebuild."

Regina Goodwin's grandfather purchased the Oklahoma Eagle in 1936, and used it to ensure Tulsa acknowledged its true history. His children, grandchildren and great grandchildren worked at the Eagle in various roles.

Goodwin has continued the fight, seeking reparations for descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre by introducing legislation. Earlier this year, she filed a bill that would appropriate $300 million for "damages to persons and property." She filed similar legislation in previous years. None became reality.

Seeking more for the people of Greenwood while grappling with gentrification

Goodwin is also working on current civil rights issues like highways and gentrification.

One of her ongoing fights is to move the crosstown expressway that cuts through the heart of Greenwood. Much of the land in the area was razed in 1967 for the building of the highway.

Now, Goodwin is encouraged by President Joe Biden's infrastructure plan that sets aside $1 billion for reconnecting neighborhoods that were destroyed by federal highways.

Luckerson said the term "blight" was often used by government officials to "in some ways, demonize properties in Black communities."

"If a property was deemed blighted, that meant the city, the state or the federal government had the right to remove it, destroy it," he told NPR. "In the Greenwood case, it's kind of a tragedy."

Urban renewal is a movement with deep roots in Tulsa, and it was based on the idea that "the community might end up being rebuilt even bigger and better," Luckerson said.

But the local authority carrying out that goal owns hundreds of acres of land in Greenwood and north Tulsa that haven't been put to any use, he said.

Kian Kamas, Executive Director of PartnerTulsa, which oversees economic development in Tulsa, says far less land remains vacant — 56 acres — and the group is working with community stakeholders on its redevelopment.

Goodwin, meanwhile, still worries about the impact of gentrification in Greenwood.

"What I would like to see is the historic residents, particularly Black folks, owning and living again in that Greenwood district, having more rooftops, having more small businesses," she said.

The digital version of this story was edited by Lisa Lambert.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.