Section Branding

Header Content

'Forever chemicals' could be in nearly half of U.S. tap water, a federal study finds

Primary Content

At least 45% of the nation's tap water could be contaminated with at least one form of PFAS known as "forever chemicals," according to a newly released study by the U.S. Geological Survey.

The man-made chemicals — of which there are thousands — are found in all sorts of places, from nonstick cookware to stain-resistant carpets to contaminated sources of food and water. They break down very slowly, building up in people, animals and the environment over time.

Research has linked exposure to certain PFAS to adverse health effects in humans, from an increased risk of certain cancers, increased obesity and high cholesterol risk, decreased fertility and developmental effects like low birth weight in children.

"This USGS study can help members of the public to understand their risk of exposure and inform policy and management decisions regarding testing and treatment options for drinking water," Kelly Smalling, a USGS research chemist who is the lead author of the new study released Wednesday, told NPR over email.

This study is the first to compare PFAS in tap water from both public and private supplies on a broad scale throughout the country, Smalling said.

It involved testing water samples from more than 700 locations across the country during a five-year period, and using that data to model and estimate PFAS contamination nationwide.

And it comes as the federal government is looking to create new regulations for toxins in drinking water.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued drinking water health advisories for two of the most prevalent compounds — PFOA and PFOS — in June 2022, warning that they pose health risks even at levels so low that the government can't detect them.

USGS tested for 32 individual PFAS compounds, and said in a release that the EPA's recent advisories for PFOS and PFOA "were exceeded in every sample in which they were detected in this study."

While the USGS — which describes itself as an unbiased and impartial science organization — doesn't offer policy recommendations in its report, Smalling points to several key takeaways.

For one, she said, it highlights the importance of collecting PFAS data from private wells, which are monitored at homeowners' discretion and not regulated by the EPA the way that public sources are.

It also has implications for the general population.

What the study found

Most state and federal monitoring programs typically measure exposure to PFAS and other pollutants at the water treatment plants or groundwater wells that supply them, Smalling said. Her team took a different approach.

"The USGS study specifically focused on collecting water directly from a homeowners tap where exposure actually occurs," she explained.

Between 2016 and 2021, scientists collected samples from 716 residences, businesses and drinking-water treatment plants from a range of protected, rural and urban areas across the U.S.

Of those, 447 rely on public supplies and 269 on private wells. The researchers found that PFAS concentrations were similar between the two.

Smalling said they observed the chemicals more frequently in samples collected near urban areas and potential PFAS sources like airports and wastewater treatment plants, which is in line with previous research.

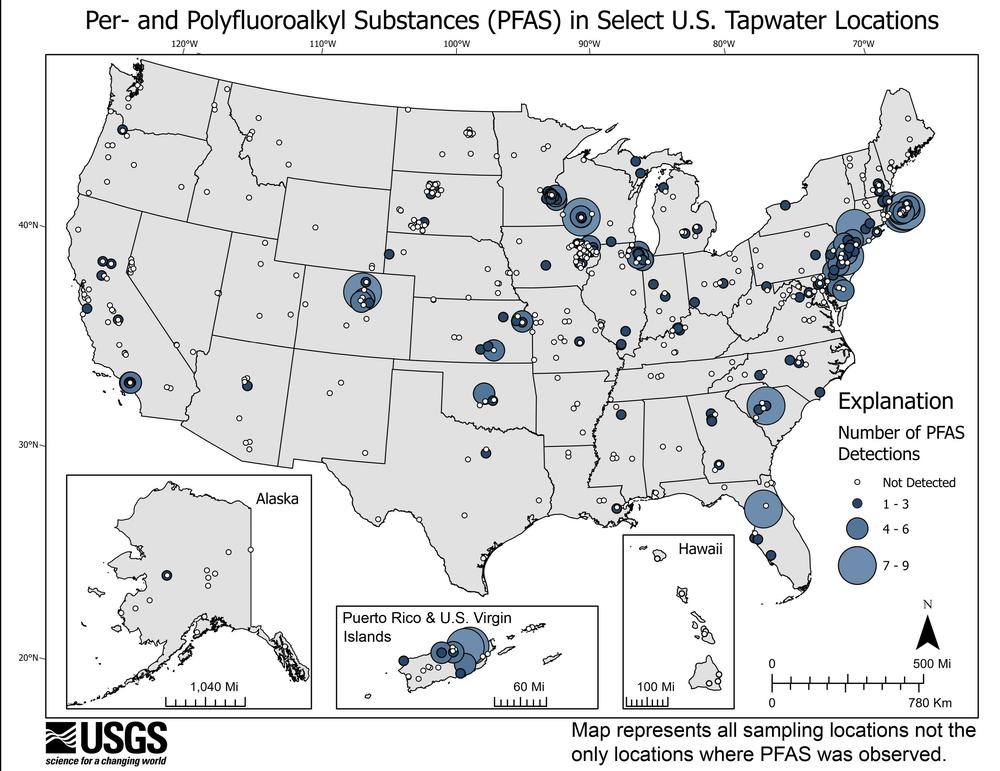

USGS scientists estimate there's a 75% chance that PFAS will be found in urban areas and a 25% chance in rural areas. And the study suggests that exposure may be more common in certain geographical regions.

"Results from this study indicate potential hotspots include the Great Plains, Great Lakes, Eastern Seaboard, and Central/Southern California regions," Smalling said.

The study says its findings support the need for further assessments of the health risks of PFAS both as a class and in combination with other contaminants, "particularly in unmonitored private-wells where information is limited or not available."

What can be done

Smalling says that USGS tap water research is continuing, with an emphasis on private well users and rural communities.

"If the average American is worried about the quality of their drinking water, they can use this and other studies to get informed, evaluate their own [personal] risk and reach out to their local health officials about testing or treatment," she added.

The EPA recommends finding out whether PFAS chemicals are in your drinking water, either by calling your local water utility or conducting regular well testing, depending on your source. Then you can compare those numbers to your state's standards for safe levels of PFAS in drinking water (or those in the EPA advisories).

If you're concerned, the EPA recommends contacting your state environmental protection agency or health department and your local water utility to find out what actions they suggest.

You could also install specific kinds of water filters that are certified to lower the levels of PFAS in water, using technologies like activated carbon treatment and reverse osmosis.

Meanwhile, there are federal efforts underway to limit forever chemicals in drinking water.

In March, the EPA proposed the first federal drinking water limits on six forms of PFAS, which it estimates could reduce PFAS exposure for nearly 100 million Americans.

The proposed regulations would require water systems to do costly testing and mitigation work and be transparent with their results, as WBUR's Gabrielle Emanuel told NPR at the time.

And they don't cover the 1 in 8 Americans who get their water from private wells and would generally be responsible for their own testing and filtration, she added.

Plus, many activists and scientists would like to see regulations that cover more types of PFAS and limit them at the source, rather than clean it them up after the fact.

The agency can make changes to its proposal based on public comments before issuing a final rule, which it aims to do by the end of the year.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.