Caption

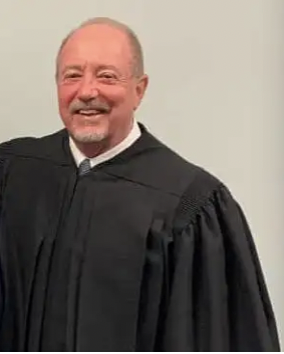

James T. Cassada (center), a former Glynn County Police drug investigator, was allowed to end his probation six years early, after he pleaded guilty in 2019 to having sexual relationships with informants.

Credit: Facebook / Edited