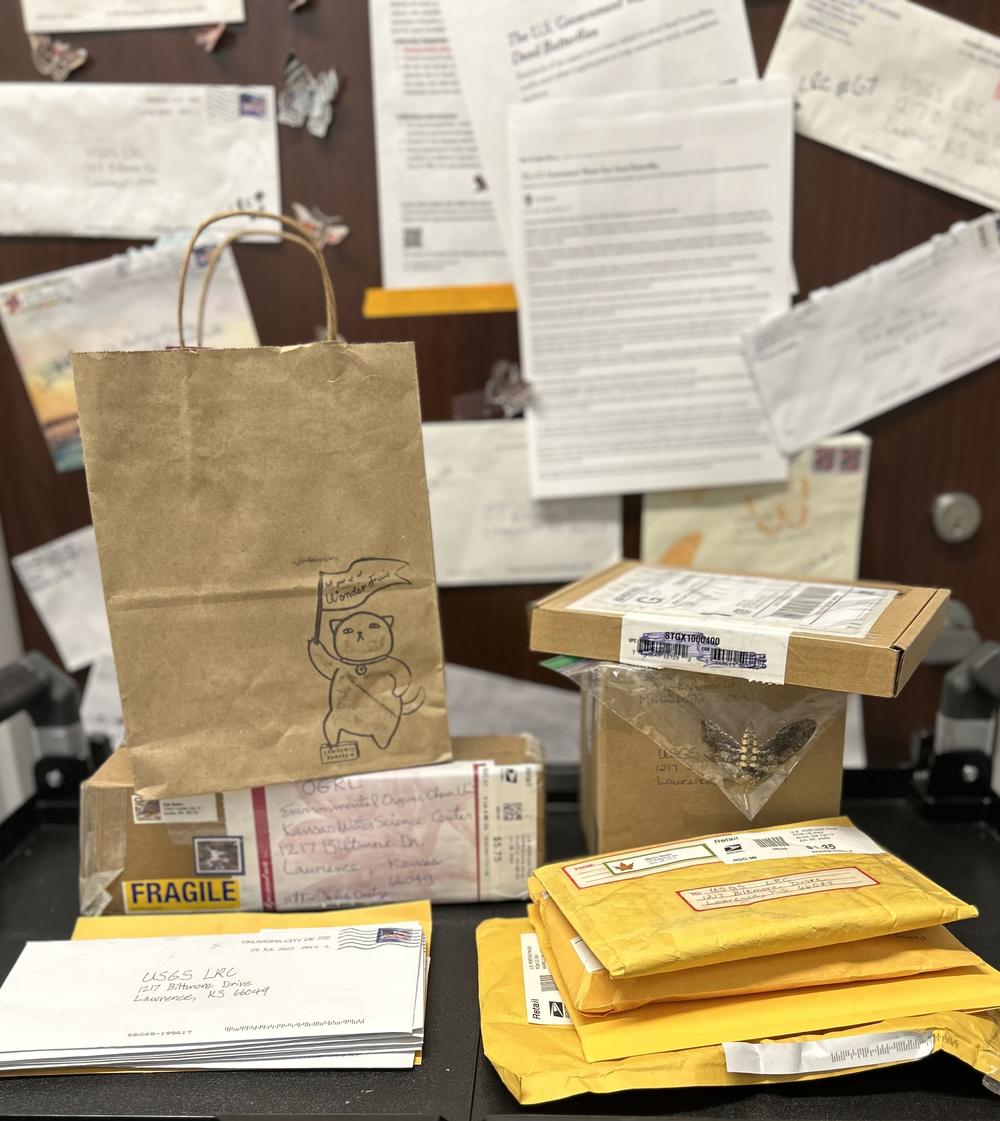

Caption

A Sphinx moth mailed from Texas to the USGS Lepidoptera Research Collection in Kansas is seen. Six states, including Georgia, constitute the area from which the scientists request butterfly and moth bodies for study.

Credit: Julie Dietze / USGS