Section Branding

Header Content

‘The Enslaved People Project’: Historic Macon-Bibb courthouse records on view at the Tubman Museum

Primary Content

A new exhibit at the Tubman Museum in Macon showcases research for The Enslaved People Project, an ongoing effort to digitize slavery transaction records found in the Bibb County clerk’s office. The records will be uploaded to a searchable database available to the public, allowing many people to have access to their family genealogy for the first time.

Discovery in the mezzanine

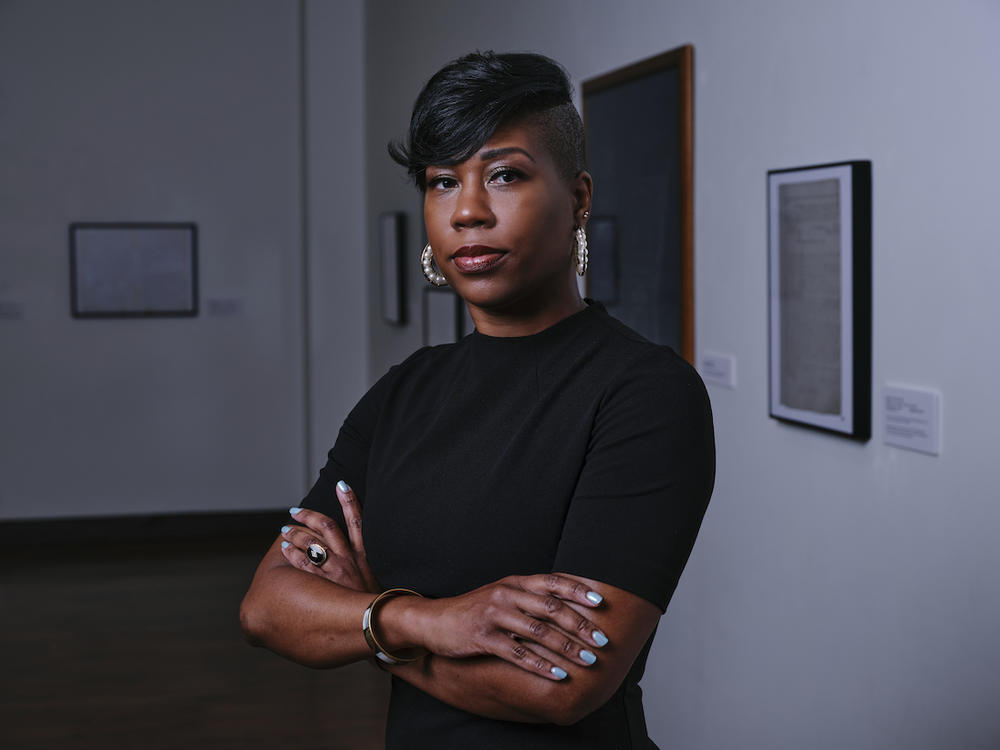

The idea for the project began in early 2013, during Erica Woodford’s first term as Bibb County Superior Court Clerk. One day she was looking through the mezzanine level of records storage and happened to open a deed book from the year 1823. There, in a handwritten list of items being sold, she found slavery transaction records. What she read was startling:

Harriet, age 11, fair complexion, long straight hair. Warranted to be sound and well for $225.

“It gave me chills. I mean, I had goosebumps on my arms,” Woodford remembered. “It was a pretty astonishing discovery.”

Old deed books contain property records, recorded transactions that convey ownership, such as selling houses or livestock. It was shocking to see human names on that list.

“I'm from Macon; I went to Mercer University and studied Africana studies,” Woodford said. “I never knew that we had those records right here in Bibb County.”

After further examination, Woodford concluded there were a total of 17 volumes containing 6,000 pages of written records from 1823 to 1865. The deed books were massive in size and heavy, with yellowed pages and small, difficult-to-read calligraphic cursive. For 200-year-old volumes, they were remarkably well-preserved.

Building a team

Woodford knew her discovery was significant. She immediately showed the records to Chief Deputy Clerk, Stephanie Woods Miller.

“It was very chilling to see them at first,” Miller remembered. “Then we began our effort to figure out how we let the world see these and what can they be used for.”

They decided they wanted to put the records into a searchable database made available for the public.

“It's about sharing the wealth, the treasure that we have right here,” Woodford explained. “Not every county has the information, because their courthouse may have been destroyed by flood or fire or some other natural disaster.”

According to Miller, many projects that deal with records during the period of slavery only focus around the slave owner. She said it was incredibly significant that their project would trace the history of a person with no name who was treated as property all the way to living people today.

“I felt very passionately that it was important that people, especially African Americans, be able to use these records to put names on their family, because that’s one of the hardest challenges for African-American family research and genealogy,” Miller explained.

Woodford met with Dr. Chester Fontenot Jr, Director of Africana Studies Program at Mercer University. Fontenot agreed to help catalogue the documents with a team of Mercer students. He was already working on a separate project called Digitizing Black Life in Middle Georgia by constructing a public database containing artifacts such as newspaper clippings and oral history recordings.

Cataloging the deeds

In 2018, Mercer received a grant called Research that Reaches Out to fund internships over two summers for Mercer students to catalog deed book information. Every day the students carefully deciphered and recorded transactions, paying special attention to each time a human being was conveyed as property. When the grant money ran out, Erica Woodford was able to find funding to continue the project.

The research entailed hours of meticulously reading thousands of pages of small, calligraphic records. Fontenot said this work was both physically and mentally demanding. Especially for people of African descent, the research took a significant emotional and spiritual toll on participants. They were not just reading statistics in a book; they were reading about real people.

“After a while you do this work and you can almost hear the cries of people being torn away from their loved ones on an auction block,” Fontenot said.

As the researchers gained a better sense of the data, they came to understand that Macon-Bibb used to be a major center for slave transactions in the Southeast. Slaveholders controlled the majority of property and were legislators in Georgia's political system.

“Slavery was not only legal; it was part of the fabric of life. It was part of the government where these deeds are in the courthouse,” Fontenot explained.

While a number of books have been written about the history of Macon-Bibb, few people before now have acknowledged the extensive role slavery played in the county’s story, Fontenot expressed. The family names of wealthy slave owners found in the deed books are still prominent on streets and buildings in Macon today. Fontenot said there shouldn’t be a need for this research project because topics like this should already be widely understood. The documents should never have been tucked away; they should already be in the public record.

Putting flesh and bones on the ancestors

Because of the disruption caused by slavery, most African Americans are not able to trace their genealogies. This is why having access to primary documents is so significant, especially for families trying to understand their history. “This whole genealogy thing is extremely important to be able to construct identity,” Fontenot said, “to be at peace, at least with your own family history, kind of put that back together, and put flesh and bones on your ancestors.”

Stephanie Miller experienced this first hand. While Miller is originally from Florida and graduated from Florida A&M for her undergrad, she discovered she had deeper ties to Macon than she expected. She was able to trace the genealogy of her husband’s third great-grandfather to a specific plantation in Macon.

“Macon was a real hub for slave trading,” Miller said. “A lot of people outside of Macon will find that they may have Macon ancestors.” The transaction records in the courthouse led her to his full name and even a photograph. Now, Miller says she’s able to tell her children where they came from.

This discovery also impacted her sister, Yvette Miller, who was the first African-American woman to serve on the Georgia Court of Appeals. Yvette told Stephanie: “Nobody understood where my drive came from. And now I can say that I know that I’m the descendant of someone who survived and thrived during slavery.”

Images of the documents are already available for public viewing on the county clerk’s E-Search website, under the historic tab. According to Woodford and Miller, the full searchable database from The Enslaved Project will be open to the public around September. The Clerk’s office is verifying each document before undergoing beta testing and publishing it to a database called Record Room. As of July, 300 documents out of 1,000 are ready for public release.

Julie Grimm is the court’s historic preservation clerk who is helping with the verification process under Stephanie Miller. “This project was here, and I just kind of stumbled upon it,” Grimm said. “I don't know, it just pulled me in and I didn't want it to continue to be forgotten.” She said the documents speak for themselves and they cannot be ignored or glossed over.

Many others in the community feel the same way. In May of this year, the Enslaved People Project received a Historic Preservation and Revitalization Award from Historic Macon Foundation.

At the Tubman Museum

The exhibit at the Tubman Museum opened on July 1. It is titled “The Enslaved People Project, 1823-1865 Selected Records from Bibb County Superior Court Clerk Erica L. Woodford, Esq., Clerk.” It features photos from the original team, copies of deeds, historical maps of Macon, and an original deed book on display from the Clerk’s office. The exhibit will be open through Aug. 14.

“It’s really exciting to have an exhibit of this sort at the museum because it's not necessarily artistic in nature, but it's definitely educational, informative, and really inspiring for me because I feel like this can inspire other counties to do the same,” Woodford reflected. “I think this is a great way to dialogue about our shared history so that we can have a better future.”

According to Fontenot, this future begins with education. We often think change can only be legislative, but “true lasting change has to occur on an individual level.” If schools can use primary source texts as educational tools, young people will grow up knowing the full, complex history of their nation. They’ll start to consider who they vote for, and what changes can be made in their communities.

Miller said the documents from ‘The Enslaved People Project’ can help spark these conversations.

“I would love for there to be more open conversations around racial disparities,” Miller said. “If a community can get past those things then they can get past almost anything.”

The Enslaved People Project will be on exhibit at the Tubman Museum through Aug. 14, 2023. To view the records online, visit bibbclerkindexsearch.com/external.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Macon Magazine.