Section Branding

Header Content

When temps rise, so do medical risks. Should doctors and nurses talk more about heat?

Primary Content

Earlier this summer, an important email popped up in the inboxes of a small group of health care workers north of Boston. The email warned them that local temperatures were rising into the 80s.

An 80-plus degree day is not sizzling by Phoenix standards. It wasn't even high enough to trigger an official heat warning for the wider public.

But research has shown that those temperatures, coming so early in June, would drive up the number of heat-related hospital visits and deaths across the Boston region.

The health risks of heat don't fall equally across the populace. But most patients at this particular clinic, Cambridge Health Alliance in Somerville, MA could be vulnerable.

And the health impacts of heat don't occur consistently throughout the summer. A sudden heat surge, especially if it happens early in what scientists call the heat season, can be especially dangerous.

"People are quite vulnerable because their bodies haven't yet adjusted to heat," said Dr. Rebecca Rogers, a primary care physician at the clinic.

The targeted email alert that the doctors and nurses got that day are part of a pilot project run by the non-profit Climate Central and Harvard University's Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, or C-CHANGE.

Medical clinicians who are receiving the alerts are based at 12 community-based clinics in seven states: California, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin.

For each location, the first email alert of the season was triggered when local temperatures reached the 90th percentile. In a suburb of Portland, Oregon, that happened on May 14th during a springtime heat wave. In Houston, that occurred in early June.

A second email alert went out when forecasts indicated the thermometer would reach the 95th percentile. For Rogers, that email arrived on July 6th, when the high hit 87 degrees.

The emails help remind Rogers and other clinicians to focus on patients who are particularly vulnerable to heat. That includes outdoor workers, individuals who are older, or patients with heart disease, diabetes or kidney disease.

Other at-risk groups include youth athletes and people who can't afford air conditioning, or who don't have stable housing. Heat has been linked to complications during a pregnancy as well.

"Heat can be dangerous to all of us," said Dr. Caleb Dresser, the director of health care solutions at C-CHANGE. "But the impacts are incredibly uneven based on who you are, where you live and what type of resources you have."

"This is not your grandmother's heat"

The pilot aims to remind clinicians to start talking to their patients about how to protect themselves on dangerously hot days, which are happening more frequently because of climate change. Heat is already the leading cause of death in the U.S. from natural hazards, Dresser said.

"What we're trying to say is 'you really need to go into heat mode now,'" said Andrew Pershing, the vice president for science at Climate Central, with a recognition that "it's going to be more dangerous for folks in your community who are more stressed."

"This is not your grandmother's heat," said Ashley Ward, who directs the Heat Policy Innovation Hub at Duke University. "The heat regime that we are seeing now is not what we experienced 10 or 20 years ago. So we have to accept that our environment has changed. This might very well be the coolest summer for the rest of our lives."

Candid talk about heat risks in the exam room

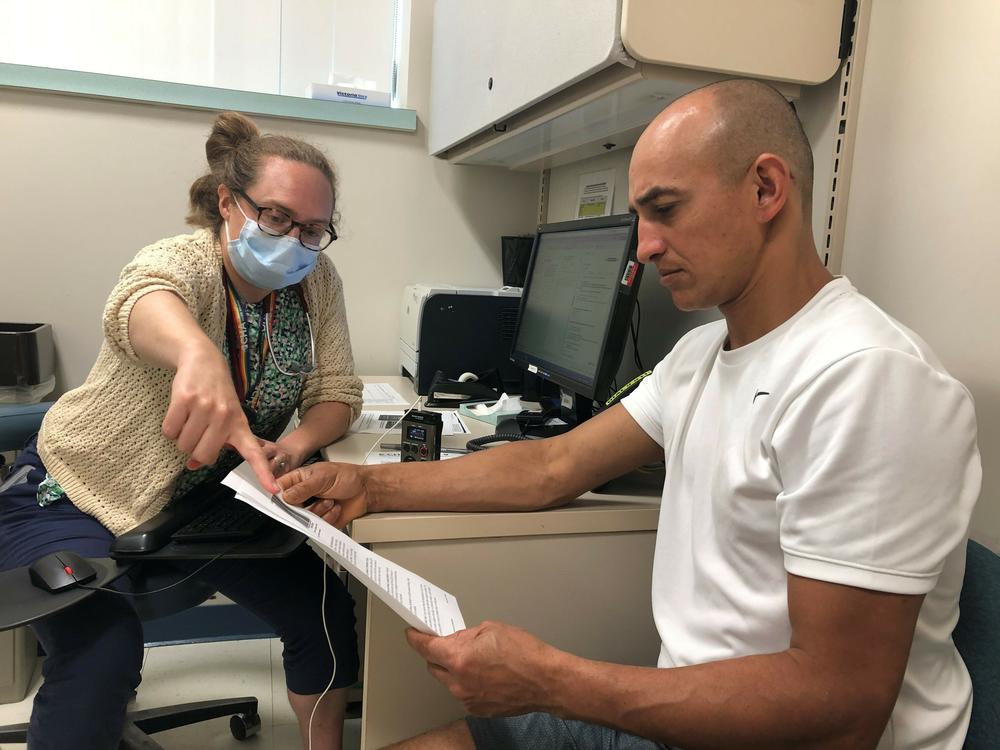

The alerts bumped heat to the forefront of Dr. Rogers' conversations with patients. She makes time to ask each person whether they can cool off at home and at work.

That's how she learned that one of her patients, Luciano Gomes, works in construction.

"If you were getting too hot at work and maybe starting to feel sick, do you know some things to look out for?" Rogers asked Gomes.

"No," said Gomes slowly, shaking his head.

Rogers told Gomes about early signs of heat exhaustion: dizziness, weakness, or profuse sweating. She handed Gomes some tip sheets that arrived along with the email alerts.

They included information about how to avoid heat exhaustion and dehydration, as well as specific guidance for patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and mental health concerns.

Rogers pointed out a color chart that ranges from pale yellow to dark gold. It's a sort of hydration barometer, based on the color of one's urine.

"So if your pee is dark like this during the day when you're at work," she told Gomes, "it probably means you need to drink more water."

Gomes nodded. "This is more than you were expecting to talk about when you came to the doctor today, I think," she said with a laugh.

During this visit, an interpreter translated the visit and information into Portuguese for Gomes, who is from Brazil. He's quite familiar with heat. But for Dr. Rogers, he now had questions about the best ways to stay hydrated.

"Because here I've been addicted to soda," Gomes told Rogers through the interpreter. "I'm trying to watch out for that and change to sparkling water. But I don't have much knowledge on how much I can take of it?"

"As long as it doesn't have sugar it's totally good," Rogers said.

Now Rogers creates heat mitigation plans with each of her high-risk patients.

But she still has medical questions that the research can't yet address. For example: If patients take medications that make them urinate more often, could that lead to dehydration when it's hot? So should she reduce their doses during the warmest weeks or months? And if so, how much? But research has yielded no firm answers to those questions.

Dealing with heat at home and outside, day or night

Deidre Alessio, a nurse at Cambridge Health Alliance, also receives the email alerts. She has a number of patients who sleep on the streets or in tents, and search for places to cool off during the day.

Alessio recently looked for an online directory of cooling centers in communities around Greater Boston, and couldn't find one.

"Getting these alerts make me realize that I need to do more homework on the cities and towns where my patients live," she said, "and help them find transportation to a cooling center."

Some heat-related health problems can set in overnight if the body can't cool down. That's why clinicians may recommend putting an air conditioner in the bedroom, if a patient can only afford one unit. But for patients who can't afford any air conditioning at all, finding resources can be hard.

Alessio and Rogers pay special attention to patients who live in neighborhoods that are heat islands, with little to no shade or natural surfaces. Heat islands can experience day and nighttime temperatures that are significantly warmer, compared to the general Boston area on which the alerts are based.

Dr. Gaurab Basu, another colleague who is getting the alerts, talks to patients about issues that may not seem related to cooling and hydration. He routinely asks patients about their social connections and whether they live alone.

"I'm really concerned about folks who are lonely or isolated," said Basu, mentioning research findings from a deadly heat wave in Chicago in 1995. "One of the major variables in whether people survived was whether they had other people they could turn to."

An intervention limited to the "heat season"

For now, Basu, Rogers and Alessio are only addressing heat risks with the patients they see during what's become known as the "heat season," which begins in late spring and can extend beyond the official months of summer.

They realize they may be missing high risk patients with appointments at cooler times of year.

Most clinics and hospitals don't have heat alerts built into electronic medical records, don't filter patients based on heat vulnerability, and don't have systems in place to send heat warnings to some or all of their patients.

"I would love to see health care institutions get the resources to staff the appropriate outreach," said Basu, who also co-directs the Center for Health Equity, Advocacy and Education at Cambridge Health Alliance.

"But hospital systems are still really strained by COVID and staffing issues."

This pilot program is an excellent start, and could benefit by including pharmacists as well, says Kristie Ebi, who leads the Center for Global Health and the Environment at the University of Washington.

Ebi has studied early heat warning systems for 25 years. She says one problem is that too many people don't take heat warnings seriously. In a survey of Americans who experienced heat waves in four cities, only about half of residents took precautions to avoid harm to their health.

"We need more behavioral health research," she said, "to really understand how to motivate people who don't perceive themselves to be at risk, to take action."

For Ebi and other researchers, the call to action is not just to protect individual health, but to address the root cause of rising temperatures: climate change.

"We'll be dealing with increased exposure to heat for the rest of our lives," said Dresser. "To address the factors that put people at risk during heat waves we have to move away from fossil fuels so that climate change doesn't get as bad as it could."

Copyright 2023 WBUR. To see more, visit WBUR.