Section Branding

Header Content

The front page of UNC's Daily Tar Heel was a gut punch. Here's the story behind it

Primary Content

Editor's note: This story includes an image displaying language that some readers may find objectionable.

The last few days have been grueling, emotional and depleting for Emmy Martin.

The Daily Tar Heel editor-in-chief helmed an edition of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's newspaper dedicated to the fatal shooting and terror that gripped the campus on Monday.

"Once we got out of lockdown, we immediately started rethinking what our Wednesday paper would look like," Martin told NPR.

The plan had been to run a football preview but after a faculty member was shot and killed, allegedly by a graduate student, Martin said it was clear that angle "was not the right tone."

Shoving aside anxiety, fear and grief, Martin said she and her team of reporters, editors and photographers worked late into the night trying to come up with a front page that would encapsulate the communal trauma of the event.

One possibility was to run a full blank page — as in, there are no words. But that didn't feel right.

Unsure, the staff called it a night. Then at around 1 a.m., scrolling through social media and texts Martin received from friends and family while hiding out from the shooter in the journalism school library, an idea solidified.

"So many students and so many friends of mine had posted messages that they had received and sent themselves to others on campus, and I knew that was going to be our front page."

Martin said the next morning she asked her staff to reach out for screenshots from messages sent Monday. A deluge of desperate, staccato missives rolled in.

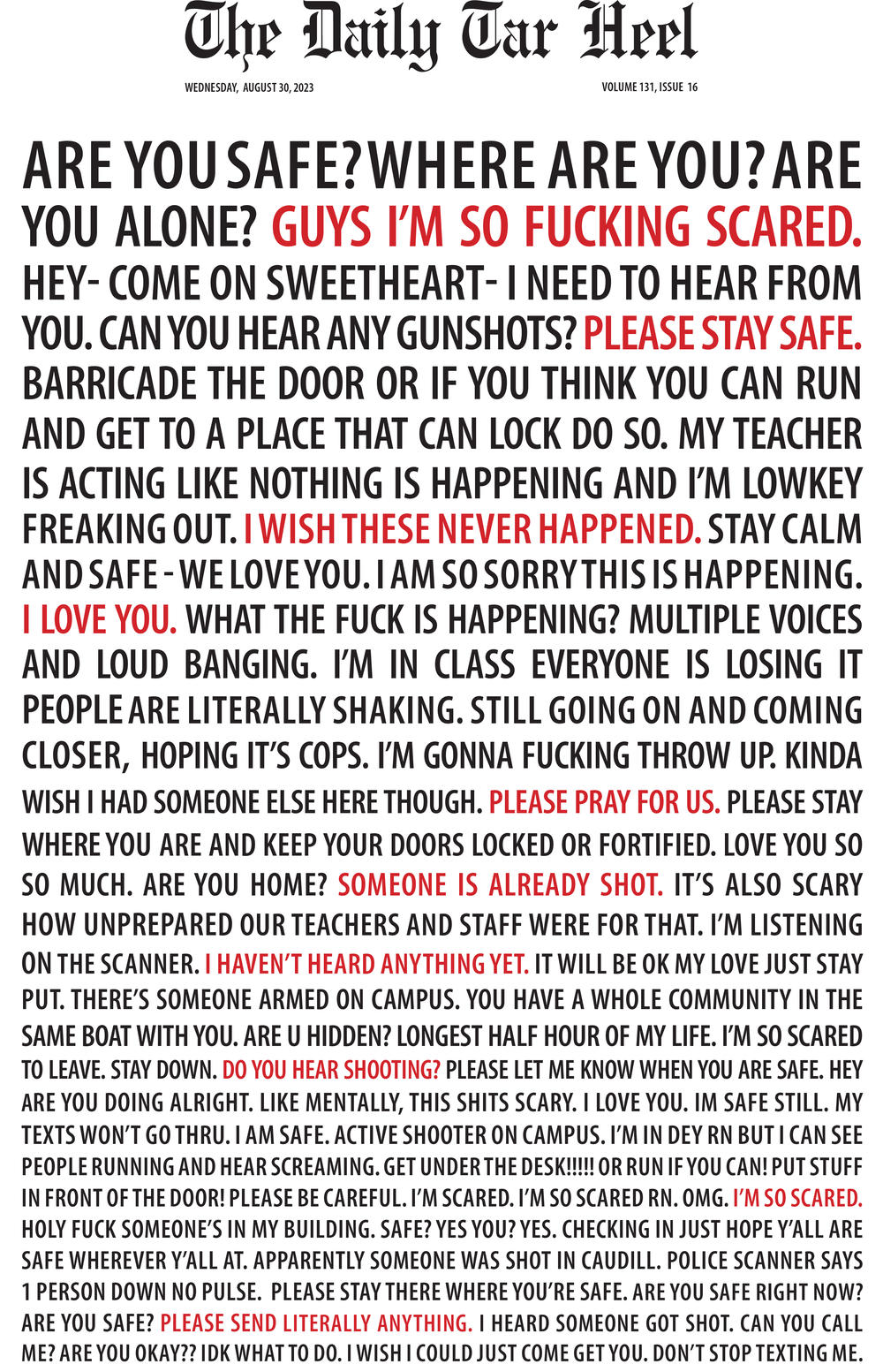

The result is stark and packs a gut-punch. A block of brief yet heart-wrenching messages, beginning with, "ARE YOU SAFE? WHERE ARE YOU? ARE YOU ALONE?"

"They were short ... and as soon as we saw those words on a blank design document, it was incredibly powerful. They just told the story of what it was like," Martin said.

The graphic has since been praised for its visceral efficacy.

President Joe Biden on Wednesday reposted an image of it on a cell phone on X, formerly Twitter, writing "No student, no parent, and no American should have to send texts like these to their loved ones as they hide from a shooter. I'll continue to do all I can to reduce gun violence and call on Congress to do the same."

Reporting the news while being the news

So far this year, there have been at least 86 incidents of gunfire on K-12 schools and college campuses, resulting in 27 deaths and 57 injuries, according to Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun-control research and advocacy group. Since 2013 — the year the nonprofit began analyzing data — there have been at least 1,117 gunfire incidents on school grounds, resulting in 371 deaths and 783 injuries nationally.

The numbers are staggering and still, they don't include the massacre of 13 people at Columbine High School in 1999. The mass shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007 that left 32 dead, making it the deadliest mass shooting in the U.S. at the time, came six years before Everytown started collecting data. And the data doesn't include the ghastly murder of 20 young children and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012.

The persistence and frequency of such tragedies means that people of Martin's generation have grown up with the threat of having to live through an active shooter scenario. And now this group of teenagers and early 20-year-olds had to report the news while also being the news. A daunting task for even seasoned professionals.

In a series of essays commemorating the 10th anniversary of the attack at Virginia Tech for the DART Center for Journalism and Trauma, several former staff members of the campus newspaper addressed the challenges of maintaining journalistic standards under dangerous conditions.

"I had to psychologically separate myself from the situation in order to focus on work. While I was obviously deeply affected emotionally by the event, in order to do my job fairly and well, I had to try and force myself to look at everything in two different ways: the mourning student and the professional journalist," wrote Kevin Anderson, who was a freshman at the time of the attack.

Others, like Bobby Bowman, who was starting his first official day as managing editor for the Collegiate Times on the day of the shooting, wrote about the challenges of being at the center of a national media maelstrom while also covering a story.

He recalled that at a certain point of nonstop work, he wondered why he didn't step back and let national news outlets tell the story. But after a much needed break he knew the answer: "The coverage is a lot different when it comes from a fellow student. We (the local news source) understand what life was like before the tragedy. We understand what the readers are going through. We understand how to cover the story wholly, yet sensitively."

That logic resonates with Martin.

Planning for the worst

Before applying for the editor-in-chief position on the Tar Heel, the college junior said she thought about how she might lead a news team through a similar crisis.

"I remember very vividly thinking, what would I do if there was a shooting on campus? How would I respond as editor and how would I also protect the well-being of my staff?," she recalled.

It was especially top of mind, she explained, because it was shortly after the Feb. 13 shooting at Michigan State University, where a gunman killed three students and injured five others.

Martin said she studied that school's newspaper for tips and insight.

"It made me talk to my adviser and other people around me just to kind of have a plan."

She said in some ways the exercise proved helpful this week "but it could never truly prepare me for the real situation."

Martin added: "I don't think any preparation will truly prepare you for the real situation. It's very different. It's more scary than I could have imagined."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Clarification

An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the sequence of mass school shootings that predated Everytown for Gun Safety's data analysis.