Section Branding

Header Content

Wonder where Hollywood's strikes are headed? Movies might offer a clue

Primary Content

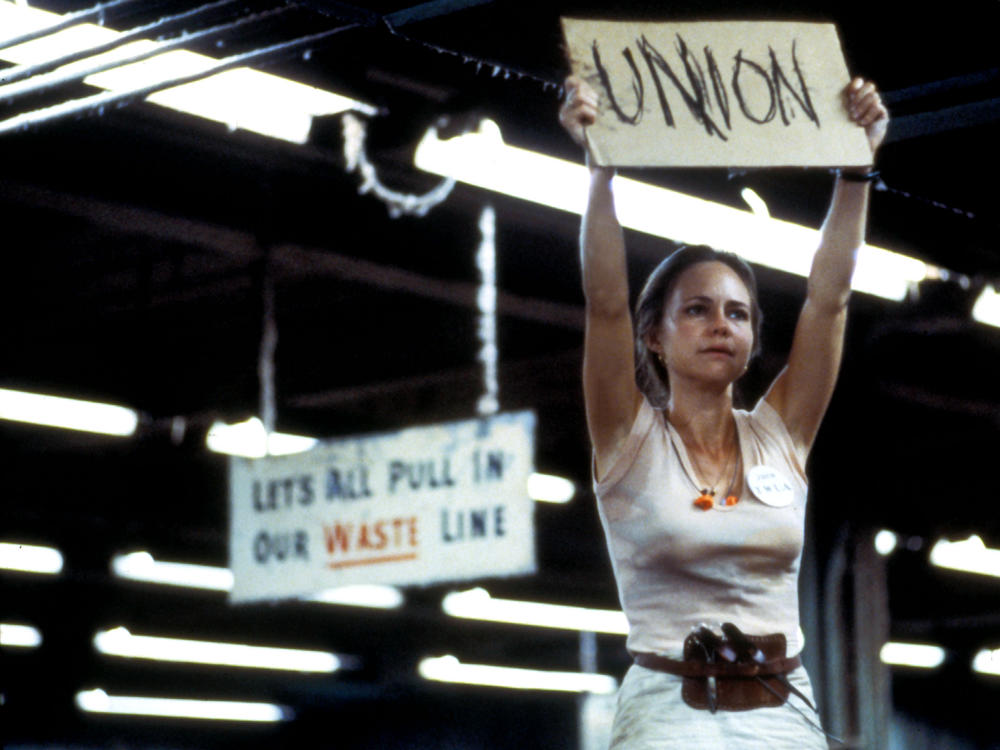

The image is iconic: Sally Field standing atop a work table in a noisy textile factory in Martin Ritt's 1979 workplace drama Norma Rae.

Her Norma Rae Wilson's just been fired for creating a disturbance at the factory, the sheriff's coming to haul her off to jail, and she's holding up a piece of cardboard on which she's scrawled just one word: "UNION."

Every eye in the factory is on her as, one by one, her coworkers, many of whom she's angered and alienated with her activism, shut down their machines in support.

For a long moment, the silence is deafening — a cinematic portrait of worker solidarity that 1970s audiences found moving at least partly because it was so rare.

Might that solidarity speak to today's Hollywood, where strikes by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) have left the film industry reeling just as it was finally recovering from the pandemic?

And might it also speak to why an August Gallup poll found the public solidly behind writers (72%) and actors (67%) in their struggles with studios?

Demonizing unions as un-American

From Hollywood's earliest days, film producers have demonized unions both on- and off-screen. Even in cartoons like Disney's black-and-white Alice's Egg Plant (1925), which depicts a pointedly Soviet "Little Red Henski," fresh off a train from Moscow, inciting a strike among Alice's previously happy hens.

Outspoken anti-communist Walt Disney was still beating that drum two decades later when he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that he thought the film industry was being taken over by communists.

"I don't believe it's a political party," he told the committee, "I believe it's an un-American thing. And the thing that I resent the most is that they are able to get into these unions, take them over and represent to the world that a group of people that are in my plant, that I know are good 100-percent Americans ... are supporting all of those ideologies. And it's not so. And I feel that they really ought to be smoked out and shown up for what they are, so that all the good free causes in this country, all the liberalisms that really are American, can go out without this taint of communism."

Disney was hardly the only movie mogul seeking to counter labor organizers in the industry's early days. MGM's Louis B. Mayer told his biographer that one of the ideas behind the 1927 formation of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), the group that hands out the Oscars, was to encourage actors, directors and designers to think of themselves not as workers, but as artists, so they wouldn't join Hollywood's technicians in forming labor unions.

Dueling visions of labor during the blacklist

All this, while Hollywood kept churning out films that depicted labor organizers as communists, and labor bosses as gangsters.

No one did that with more urgency than Elia Kazan in 1954's On the Waterfront. Two years earlier, at the height of the Hollywood Blacklist, which barred from employment any worker who was alleged to have subversive inclinations, Kazan had named names to HUAC. Reviled by many in the industry for destroying careers by doing so, he offered On the Waterfront as a rebuttal of sorts, with hero Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) depicted as noble for testifying against corrupt union bosses.

A more affirming portrait of labor organizing, Salt of the Earth was also released in 1954. A story of Mexican American miners and their wives battling prejudice and unfair labor practices, it was created outside the studio system, said its producer Paul Jarrico, by artists who could no longer work inside it.

"One of the reasons we made Salt of the Earth after we were blacklisted," he recalled years later, "was to commit a crime worthy of the punishment."

The film, in which real mine-workers and their wives essentially re-enacted their own 15-month struggle, is regarded today as a classic, though the major studios blocked it from being widely shown in the 1950s by threatening to boycott theaters that played it.

And what was a more typical studio portrait of labor relations back then? — factory worker Doris Day pushing for an extra seven-and-a-half-cents an hour in the 1957 film version of the Broadway musical The Pajama Game.

It was labor relations played for laughs with song and dance, though the laughs had maybe soured for studio heads by 1960. That's when both the actors and the writers last went on strike together. (In an odd twist, the head of the actors' union who called for that strike was Ronald Reagan, who would later campaign against "big labor" as President.)

Independent filmmakers take labor's side

In any event, there weren't a lot of jokey movies about labor for a while. But in all the decades since, Hollywood has never stopped making films about union corruption — from Paul Schrader's Blue Collar (1978) with Detroit auto workers Richard Pryor and Harvey Keitel uncovering their union's malfeasance when they try to rob it, to Martin Scorsese's The Irishman (2019) about a hit-man who claimed to have killed Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa.

Still, with the decline of the studio system, independent filmmakers began exploring labor stories that centered on the little guy in, say, the coal-mining documentary Harlan County, U.S.A. (1976), or in John Sayles' mining drama Matewan (1987) set a half century earlier. James Earl Jones had to contend in that one, not just with management, but with the guys down in the mine. He could brush off their racial invective, but bristled at being called a "scab." And union organizer Chris Cooper backed him up.

"You ain't men to that coal company, you're equipment," he told miners who'd assembled to hear his pitch. "They'll use you, 'til you wear out, or you break down, or you're buried under a slate fall. And then they'll get a new one. And they don't care what color it is or where it comes from."

Taking cues from the ancients

Now, a couple of things are worth noting. The first is that stories about strikes go back at least to ancient Greece. In 411 BC, Aristophanes' comedy Lysistrata had war-weary Greek wives going on a sex strike to force their husbands to negotiate peace (a storyline Spike Lee adapted in his 2015 comedy Chi-Raq about gang wars in Chicago).

Also, note that this genre is more robust overseas than in the U.S.. Sergei Eisenstein arguably started it with his 1925 silent epic Strike, an artful piece of widescreen Soviet propaganda about class war between virtuous workers and vicious overlords. Foreign film stars have long embraced labor sagas, from Marcello Mastroianni in the neo-realist Italian drama The Organizer (1963), to Gerard Depardieu in the French costume epic Germinal (1993).

In England, while Ken Loach was crafting such social-realist worker dramas as Bread and Roses (2000), and Sorry We Missed You (2019), a whole sub-genre of worker-comedy sprang up around him: former steelworkers in The Full Monty (1997), out-of-work musicians in Brassed Off (1996), queer activists raising money for striking miners in Pride (2014).

But another thing to note is that if money is the measure of these films, the studios are winning. Star-studded gangster epics are a blockbuster genre, and no matter how inclined audiences are to root for the little guy, human interest sagas can't compete commercially.

Not even when they're given the full Little-Mermaid-treatment by composer Howard Ashman and lyricist Alan Menken, as Newsies was in 1992. Their punchy, dance-powered film set New York's 1899 newsboy strike to music, with Christian Bale heading a starry cast that included Bill Pullman, Robert Duvall, and Ann-Margret. But even with a surprisingly modest $15 million production budget it flopped, earning less than $3 million at the box office for — of all studios — Disney.

Still, you can't accuse the studio of burying it. Twenty years later, Disney's stage version of Newsies played more than a thousand performances on Broadway, and toured across the country, all because that central little-guy-against-the-world story is still potent, whether it involves David and Goliath, or workers and bosses.

Or ... artists and studios.

Edited by Rose Friedman

Audio story produced by Isabella Gomez

Digital story produced by Beth Novey

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.