Section Branding

Header Content

John Blake: More Than I Imagined

Primary Content

Award-winning CNN journalist John Blake grew up a self-described “closeted biracial person,” hostile toward white people while hiding the truth of his mother’s race. In this episode of Narrative Edge, Peter and Orlando explore a powerful conversation with Blake about racial reconciliation, acceptance, and empathy.

Peter Biello: Coming up in this episode.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah. If somebody is murdered and it's not white or a homeowner, we're not going to really pay attention to it.

Peter Biello: While he's told that explicitly.

Orlando Montoya: mm-hmm.

Peter Biello: Yikes.

John Blake: I grew up there as what I call a closeted biracial person. I had this white mother.

Orlando Montoya: He thought his mom was dead.

Peter Biello: Really? Wow.

Orlando Montoya: They never even spoke of the mom.

Peter Biello: And then suddenly. "Oh, yeah, she's alive. You want to meet her?"

Orlando Montoya: Yeah.

Orlando Montoya: This podcast from Georgia Public Broadcasting highlights books with Georgia Connections hosted by two of your favorite public radio book nerds, who also happen to be your hosts of All Things Considered on GPB Radio. I'm Orlando Montoya.

Peter Biello: And I'm Peter Biello. Thanks for joining us as we introduce you to authors, their writings, and the insights behind the stories mixed with our own thoughts and ideas on just what gives these works the Narrative Edge.

Orlando Montoya: How's it going?

Peter Biello: Pretty good. Pretty good. You know, I'd ask you if you'd read any good books lately, but we wouldn't be in the studio if you hadn't.

Orlando Montoya: We're always reading good books.

Peter Biello: So what do you got for us this week?

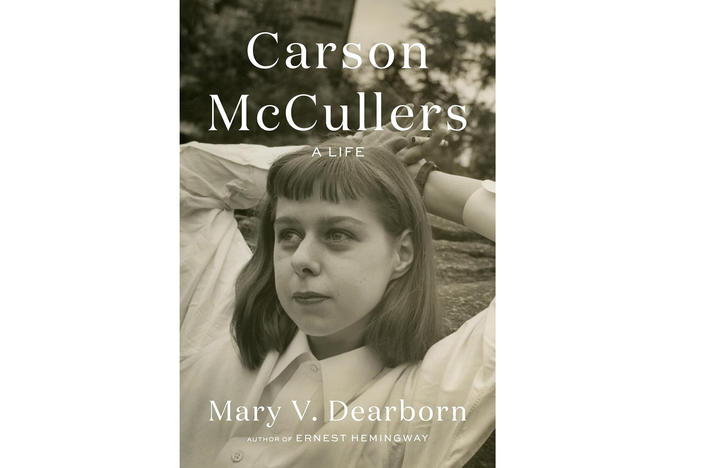

Orlando Montoya: I got John Blake's More Than I Imagined: What I Discovered About the White Mom That I Never Knew Existed. John Blake, he is a senior writer with CNN and he covers the race beat. So he's been talking about race for a long time. He really is one of our foremost writers in America about race. And he's now based in Atlanta.

Peter Biello: And it seems like he's now writing something personal as opposed to journalism.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, I would say this is his most personal, his most in-depth exploration of race. It really blends his own story with the national story.

Peter Biello: Okay. So where does his story start?

Orlando Montoya: Well, his story starts in Baltimore. He grew up with a white mother that he never knew and a Black father. And this was rough-and-tumble Baltimore, we're talking 1980s, a lot of poverty, a lot of crime. This was really The Wire Baltimore.

Peter Biello: Okay.

Orlando Montoya: So we're talking he didn't see any white people at all in his existence went to pretty much all black school. And on top of all this, he had a secret.

John Blake: I grew up there with this secret. I grew up there as, what I call, a closeted biracial person. I had this white mother and this white family. But the catch was also that I knew nothing about them. My mother disappeared from my life not long after I was born, and her family didn't want anything to do with me because I'm Black. And so I grew up knowing that there was this white side of my family wanted nothing to do with me because of their racism. And in this world where everybody hated white people, so I didn't want anybody to know I had a white mom.

Orlando Montoya: And on top of all this, he's got an absent father. His father is off sailing. He is in the Merchant Marine. So he's put in foster homes, these really horrible foster homes. He talks about, you know, not getting enough food to eat, getting physically abused. One evil character in the book is a woman he called Aunt Fannie, who ran one of these foster homes. And he tried to escape multiple times, sometimes with his brother. He would just go out and say, we're going to, we're going to escape today. And they would always end up having to come back to Aunt Fannie's.

Peter Biello: So given where he is now, you know, famous journalist, able to write a book, he clearly succeeded in life. How did he get himself out of that environment?

Orlando Montoya: Well, it is school. He studied hard. He was — he excelled in in his school. But he also had people who cared about him. A great character in the book is Aunt Sylvia and his brother, Pat. Aunt Sylvia would always check in on him. By the way, he calls a lot of people "aunt" in the book. I guess that's just the way. But Aunt Sylvia was a genuine aunt and was generally caring about him and also his brother, Pat. So he he goes to college as well. But before that, he makes another painful discovery. And that is one day when his father says to him, "You want to meet your mom?" Like out of nowhere, "you want to meet your mom?"

Peter Biello: And so that is not a casual question.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, he thought his mom was dead.

Peter Biello: Really? Wow.

Orlando Montoya: They never even spoke of the mom.

Peter Biello: And then, suddenly. Oh, yeah, she's alive. You want to meet her?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah. So they trek out and go to a hospital. Imagine you're in the waiting room of a hospital.

John Blake: And I hug her. It is awkward for me because I don't know what to say. I had never even used the word "Mom" before. But it's also awkward because of where we're standing. It's the waiting room of a mental institution, and nobody in my family told me that she was mentally ill. We didn't make that discovery until we were in that waiting room and hugging her. So that was what — what — that's one of the reasons it was so painful. It was a shock. Nobody prepared us.

Orlando Montoya: What a shock.

Peter Biello: Yeah, to not see your mother and then to see her and realize that she's — she's very ill.

Orlando Montoya: She has schizophrenia. So she was institutionalized, I guess it was shortly after he was born, maybe, I think 5 or 6, he said, or or even earlier than that. But the point is that now he's got two things in his mind that he has to erase his mom for: being white and being mentally ill. But he goes off to college and only sees her periodically. Not very much contact, forgets about her really. He goes to Howard University, you know, Howard Washington, D.C., one of the foremost Black institutions in America. He gets a scholarship there and he ends up at a Chicago internship in journalism. And that's where he meets this Christian group. And the Christian group is one of the turning points in his life.

Peter Biello: How so? What did the Christian group do?

Orlando Montoya: Really, it taught him how interracial people can be.

Peter Biello: All right.

Orlando Montoya: Because, you know, he's going to an all-Black school and but he now gets out into the world and he discovers this group has got white people and Black people. And there's this one scene in the book that I remember because it touches me personally a little bit. He he gets involved in this Christian group, and so far everything's interracial. He goes to all the groups, everything's interracial. And then one day he shows up at the group and he looks inside and they're all white people. And he's like, I don't know. Do I fit in there? And, you know, that's sort of personal for me because, you know, I've I sort of felt at times of my life I didn't fit in whether it was my weight or my sexual orientation or different things. You just sort of look at people and say, do I fit in there? And that's where he put it in his mind. And he said, I do fit in there. And so that was a turning point. And then he moved to Los Angeles.

Peter Biello: Moves to Los Angeles. Okay. And is he a journalist there?

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, he becomes a journalist and that's where he starts to talk about race.

Peter Biello: Okay. What inspired him to do that there was that I mean, that was the Rodney King days, wasn't it?

Orlando Montoya: Rodney King! I knew you were going to get you would figure it out. You would figure it out. L.A., race, Rodney King.

Peter Biello: So was that the first story he had to cover?

Orlando Montoya: No. No. He was covering crime story. You know how you start out and you start you start covering the crime beat and on the crime beat. That's when one of his editors told him, yeah, if somebody is murdered and it's not white or a homeowner, we're not going to really pay attention to it.

Peter Biello: Wow. He's told that explicitly.

Orlando Montoya: Mm hmm.

Peter Biello: Yikes.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah. So he, he he learns about race on the job and he becomes really one of the foremost experts on reconciliation. But it's not really a term that he likes; he doesn't like this term "reconciliation."

John Blake: When a Black person tells a story about reconciling with the white person, it's often seen as one of these Disney kind of "Blind Side" stories where the burden of forgiveness is placed on place on Black people. And, you know, we all live happily ever after. This wasn't that type of story. It was — what I learned about reconciliation, it was extremely difficult. I had to convince members of my white family who wanted nothing to do with me because of my race, who freely used the N-word, that they had problems with race.

Orlando Montoya: So he did that just over the course of — it took years and years and years. So he's going through all of his personal stuff while his journalism career is going on. He moves to Atlanta, becomes a reporter with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and here he discovers an interracial church.

Peter Biello: Hmm. Okay. And all the power dynamics that come along with that, I guess.

Orlando Montoya: And all the power dynamics that come along with that. You know, I attend a church. We — we profess to be very anti-racist and but at the same time, we don't have in our church a lot of Black people. We have some, but it's still majority white. In this particular church — it was Oakhurst, it was called here in Atlanta — he described it as being, you know, roughly 50/50. And not only that, Black people had power, the white people had power. And it sometimes conflicted. But he is very explicit in this book. One of the main points is that you have to have contact like that for racism to end.

Peter Biello: And so did that contact end up changing the way he thought about his own family?

Orlando Montoya: Yes, indeed. Because as he mentioned, he had these racist white people in his own family. And his aunt ends up sort of being a villain in the book. But the aunt comes around and I want to tell you the situation. The aunt didn't have anything to do with him as a child. And then again, one day she out of the blue says, "you know, I want to get to know you" or, you know, "let's get together." And he's skeptical initially.

John Blake: She became like a heroine in the story. Somebody is this great example. She changed in ways that I never expected. She taught me lessons about empathy and forgiveness that I never expected. So that was really surprising that all these people that I met in my mother's family, that I — I saw them as villains. But I wasn't prepared for my reaction that they would become people that I would love.

Peter Biello: Wow. Okay. So he sounds like he comes to good terms with his family. Does that change the way he also thinks about race in America overall?

Orlando Montoya: I mean, I wouldn't call it optimism from him. I would call it realism. You know, we have to do the work. This is the — the point of the book. You have to do the hard work of being in contact with people and not just being in contact with people on a superficial level, but, you know, on on a — on a real basis, like at like at a workplace or a school or in the Navy or something like that. It's the contact theory of — of, of racism that was propounded by a man named Gordon Allport in a famous book.

John Blake: There is a belief now that racism is embedded in people that we can't change. Allport and his contact theory blows that to pieces and say, no, that's not true. Racial attitudes can shift. And we know because we've done so many experiments and studies, when you get different people of different races together in these certain situations, racism will decline. And he talked about certain conditions. Like you said, they have to share roughly, roughly equal status. You know, slaves and slave masters had physical proximity, but that didn't lead to more understanding. But when you bring different people together — and here's the thing that's really important about it: If you bring different people of different races together to talk about race like, say, racial reconciliation, he said, that has limited impact. But what you do is you bring together different people for something larger than race, for a larger common purpose, and that's when the magic happens. So, for example, when people go into the military.

Orlando Montoya: So like I said, his father was in the military. And in the book, he describes his father as as, of course, he was subjected to racism, but he didn't have the same hatred of white people as I think he did growing up.

Peter Biello: Well, let me ask you about this, because it's making me think. We've mentioned anti-racism a few times. Right. And I know this book is not a book about policy. It seems like a very personal book. Correct me if I'm wrong.

Orlando Montoya: Yes.

Peter Biello: Yeah. So the — the the guru of anti-racism, right? Ibram X. Kendi, he talks about racism as being a function of policy that essentially racist ideas come from policy ideas first. It's not the other way around. It's not racist beliefs from people lead to the policy. It's the policy that leads to the racist beliefs as justification for that policy. Does — does Blake wrestle with that at all, with the policy angles here?

Orlando Montoya: He does. I mean, I actually have it right on here to go to page 111.

Peter Biello: Oh, okay. Our notes come in handy for a change.

Orlando Montoya: And wouldn't you know it, I left the book in the other place.

Peter Biello: Booo. Oh, okay. Well, we could pause if you want to go get it. Let's put in the podcast some of that waiting room music.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah.

*waiting room music*

Orlando Montoya: All right, So I'm back.

Peter Biello: Okay.

Orlando Montoya: I've got the book here and we're talking about policy. And on page 111, he talks about the desegregation of American schools. And he said this process accelerated into the '80s. And basically, he was saying that during this period that peaked in 1988, the U.S. saw its greatest racial convergence of achievement gaps in educational attainment. So the policy, desegregation, led to the outcome of improved test scores for Black students without compromising the white students. And of course, since then, we've — we've slid on that. But yeah, so he does go into policy. But I think it's really the the weaving of the personal and the policy, the societal that I think gives this the book the Narrative Edge.

Peter Biello: I'm glad you told me that. That was my next question. What gives this book the Narrative Edge?

Orlando Montoya: I will say that this book resonated for me, very much so, because I, too, have people in my family that we don't talk about. I have a half-brother who had mental illness and no one talks about him in our family. He died violently when I was young.

Peter Biello: I'm sorry to hear that.

Orlando Montoya: And no one talks about him. So I have questions about my family, and I wanted to know from him, you know, some advice. So I had him in the studio. I'm like, "what advice would you give to people who have, you know, secrets in their family that — that they want to talk about?"

John Blake: I think one is to understand that those painful truth will come out sooner or later. So you — it's best to get ahead of them. Because I think what people often try to do is they try to hide them and hope they never come out. But they do. And so, too — and when they do come out, whichever way they come out, I would say to hopefully make make sure that people are ready psychologically mature-wise to hear it. I don't know if I could have understood some of the things about my mom and her family if they had told me, say, when I was 7 or 8. I think they had to wait until I was older. I mean, I'm still trying to understand some of this stuff that happened in my mom's family.

Peter Biello: Well, do you think his work as a journalist kind of helped him get to this point as well?

Orlando Montoya: I think so, because, you know, we as journalists have questioning abilities. But I sometimes think to myself, you know what, I really wouldn't want to go up to my father and be like, "Hey, dad, let's have an interview about the person we never talk about."

Peter Biello: That is a hard conversation to start.

Orlando Montoya: Yeah, I mean, I asked him, how do you — how do you — how do you start that, that conversation?

John Blake: What someone told me before I did this is that you have to treat your family like a source. You have to interview them. You think you might think you know your story, but you don't. And you might think you know your father or your mother's story, but you don't. And that was so true as a journalist. I had to — that kind of training, you know, interviewing people, you know, asking them questions, talking to them again and again. That was invaluable in telling the story. And I don't think if I was a journalist, I could have gotten to some of the discoveries, the revelations, that I had in the book.

Orlando Montoya: So that's it. That's the book More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew by John Blake.

Peter Biello: Orlando, thanks so much for telling me about it.

Orlando Montoya: All right. We'll be back next time with one of your books.

Thanks for listening to Narrative Edge. We'll be back in two weeks with a brand-new episode. This podcast is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Find us online at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge.

Peter Biello: You can also catch us on the daily GPB News podcast Georgia Today for a concise update on the latest news in Georgia. For more on that and all of our podcasts, go to GPB.org/Podcasts.