Section Branding

Header Content

Inside Georgia’s Opioid Epidemic

Primary Content

Every day in the United States 91 people die of opioid overdose. That includes prescription opiates and heroin. Over a year, that’s more than ten times the number of people who died on 9/11. On today’s “On Second Thought,” we’re going to hear from some of the people struggling with addiction, those who offer help, and communities caught in the middle.

Usually on Fridays we bring you a roundup of the week’s news in the Break Room. But today we’re going to break with tradition.

Inside Georgia’s Opioid Epidemic

You know that Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9u-TITxwoM

The basic idea is everyone in Hollywood – no matter how famous or fringe – is connected to the actor by six or fewer acquaintances? Chances are your connection to the opioid crisis is even closer. Most of us are only a few steps away from someone who’s struggled. It may be a neighbor, a co-worker, a friend, a family member, or even yourself.

In the United States we have five percent of the world's population, but we consume more than 80 percent of the world's opiate supply. Some of it is legal – think that hydrocodone your kid got when she had her wisdom teeth out – and some of it isn’t.

Twice a week, a small group of volunteers operates Georgia’s only syringe exchange in the hulking shadow of an abandoned stone church in Atlanta’s English Avenue neighborhood – a place known as the Bluff.

Intravenous drug users come here to trade their used needles for clean ones.

These are just some of the people who struggle daily with opiate addiction.

But what’s going on in their brains? Why can some people experiment with drugs or take a painkiller and not become addicted, while others do, easily?

Think of it this way: Imagine that you haven’t eaten in several days. What would you be thinking about? Food – of course! The craving for food is actually the brain’s mechanism that drives you to survive. That is how many people describe what it’s like to be addicted to opiates.

Sam Snodgrass is one person who knows all too well about that craving. Snodgrass was addicted to heroin back in the late 1970s. All of this happened while he was working to study the effects of drugs on the brain as part of a post-doctoral fellowship to become a behavioral pharmacologist.

Today, Snodgrass sits on the board of directors for Broken No More – an organization that helps with substance abuse recovery. He talked to GPB’s Leah Fleming.

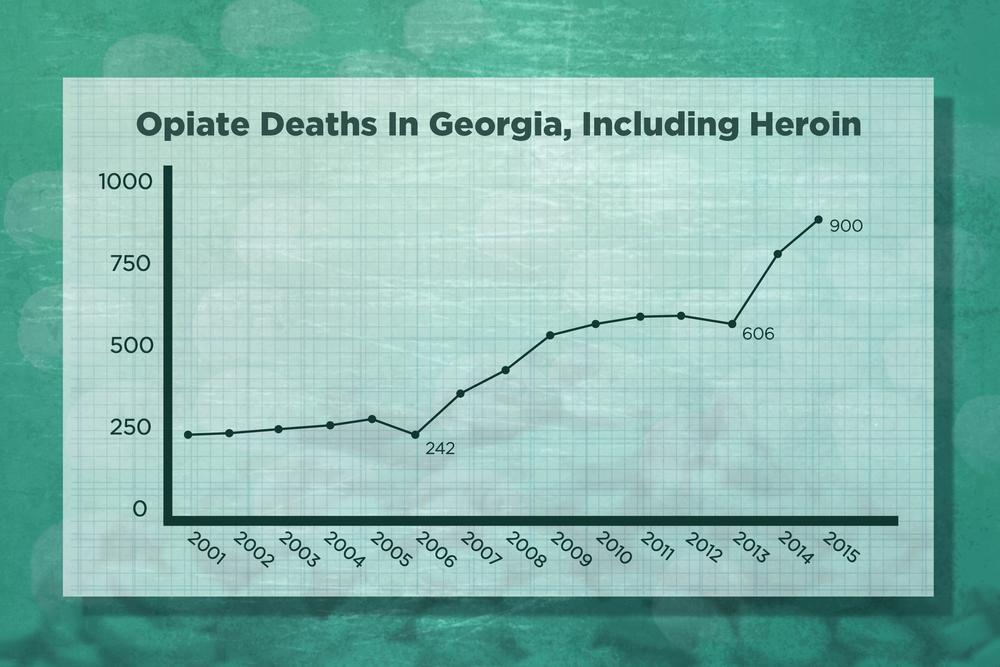

Here’s a startling fact: the number of overdose deaths nationwide jumped 72 percent from 2014 to 2015. Over just two days in June, 33 people OD’d on opiates in central Georgia. Five of them died.

Law enforcement tied the outbreak to a street version of counterfeit Percocet laced with fentanyl. The Centers for Disease Control says fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. It’s dangerous, and it’s changing the way law enforcement does its job. GPB’s Josephine Bennett reports.

Drugs like fentanyl aren’t just creating new risks for human police officers. The dogs who use their powerful noses to sniff out drugs are inhaling the dangerous synthetic opioids as well. As GPB’s Emily Jones reports, police departments are taking new steps to protect their dogs – and respond if the K-9s get sick.

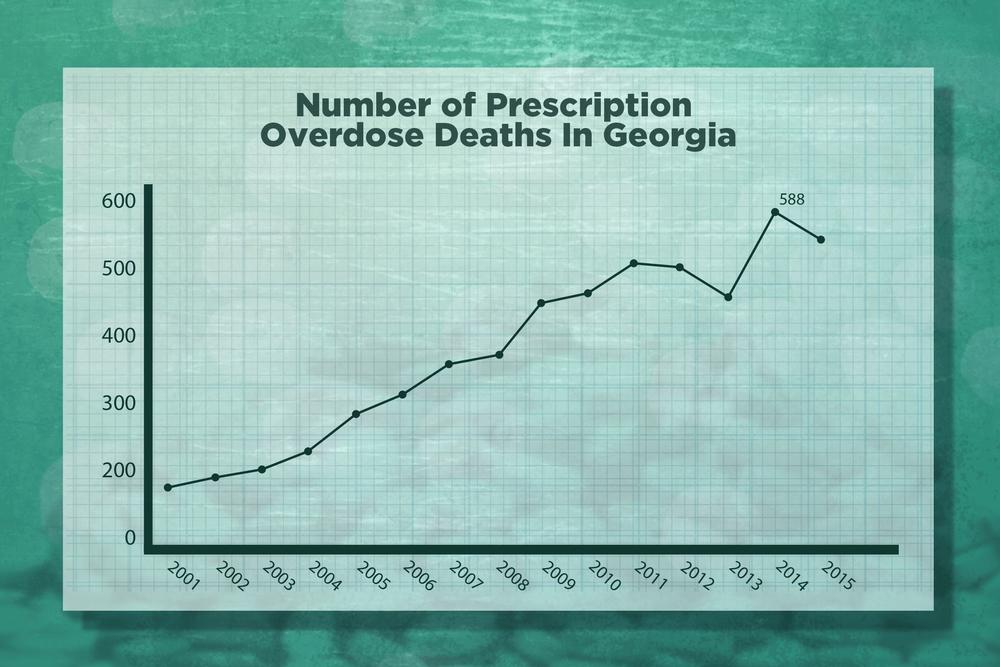

Around 75 percent of heroin users started with a prescription opioid – drugs like Oxycontin, Vicodin and Percocet. Here’s former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pdPrQFjo2o&t=248s

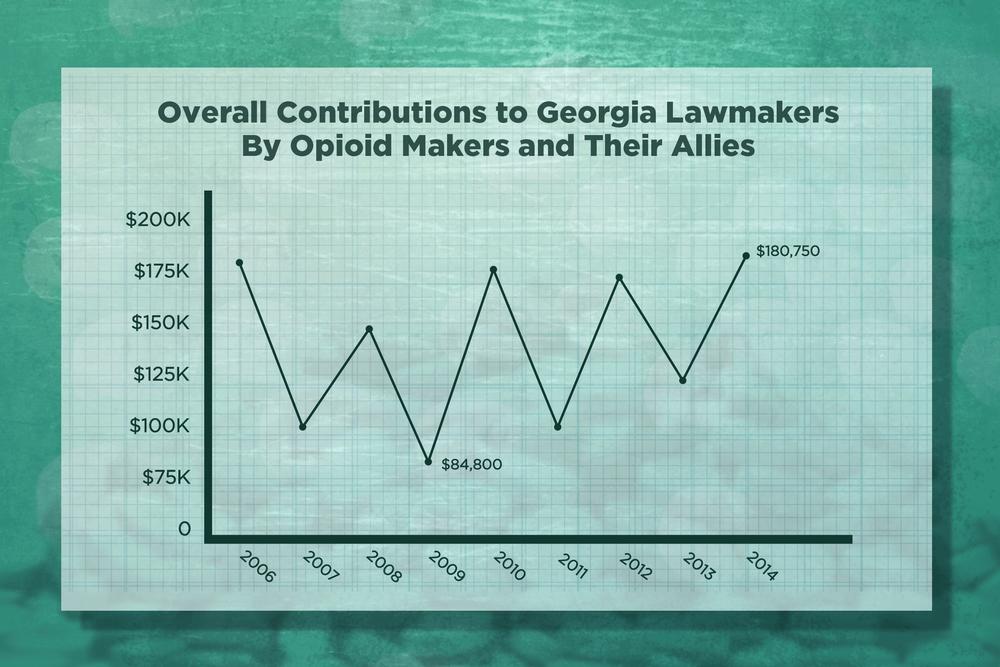

The prescription opioid business is big. $10 billion a year big.

A team of journalists with the Center for Public Integrity has been investigating how pharmaceutical companies are profiting from the opioid epidemic. GPB’s Rickey Bevington talks with reporter Liz Essley Whyte about their findings.

How do you fight pain while fighting addiction? That’s a question that’s on the mind of health care providers all over rural Georgia. In these settings where doctors are scarce, nurses and physicians assistants are key providers of care. But some worry the state’s effort to fight opioid abuse has left those providers without and important tool. GPB’s Sam Whitehead reports.

While there’s no question the opioid epidemic touches every part of our country, the most recent numbers from the CDC suggest the problem is in decline in some places — including Albany, Georgia, in the southwest corner of the state. Dr. James Black is the director of emergency medicine at Phoebe Putney Medical Center in Albany. He says he knows his community is better off than some, but he's still painfully aware of opiate overdoses.

Treating overdoses is hard, but if you’re a civilian witnessing a drug overdose can be truly frightening. But many people who find themselves in that situation are hesitant to dial 911 for fear of the consequences. Three years ago, Georgia passed a medical amnesty law that offers limited legal protection for overdose victims and those who call for medical assistance. GPB’s Taylor Gantt takes a look at the law and how it’s being put to use.

A new kind of tourist is visiting Georgia. And they’re not here for our national parks, beaches, or aquarium. They’re here for methadone, a drug that treats opioid addiction by blocking withdrawal symptoms. Georgia has more than 70 clinics, the most of any state in the South. GPB’s Olivia Reingold brings us this story from the state’s Northwest corner, where many of these clinics are clustered.

The opioid epidemic isn’t just causing tension in communities with methadone clinics. It’s also raising a lot of questions for businesses, particularly in rural areas of the state. Georgia’s unemployment rate is at record lows, but some companies are having trouble finding workers who can pass a drug test. In Stephens County, in the northeast, jobs are unfilled because prospective employees can’t pass drug tests. GPB’s Stephen Fowler has this story from Stephens county in northeast Georgia.

Georgia’s opioid crisis cuts across race, class, and age. And solving this nationwide public health emergency is no easy task. But all across Georgia, people are working to curb the epidemic.