Section Branding

Header Content

With More Transparency On Election Security, A Question Looms: What Don't We Know?

Primary Content

Americans have the most detailed accounting they've ever received in real time about foreign efforts to interfere in a U.S. election — but, for the public at least, there are still as many questions as answers.

The U.S. intelligence community has made good on earlier promises to release some findings and assessments on foreign interference, including with a historic report last week from the nation's top boss of counterintelligence.

The latest word came Wednesday, when Assistant Attorney General for National Security John Demers described what he called the need for the United States to order the closure of the Chinese government's consulate in Houston.

Not only was it involved in what officials have called a tidal wave of espionage efforts directed by China toward the U.S., but it also played a role in Beijing's covert influence operations, Demers said — without giving more detail.

It was was playing a role "on the covert foreign influence side of things, which we, at least at this point, can talk at lot less about — but I hope one day we'll be able to talk more about. So that's why Houston was not chosen at random out of the consulates out there."

Demers talked via videoconference in a session streamed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, promised earlier he would be "providing updates to the American public, consistent with our national security obligations. The steps we have taken thus far to inform the public and other stakeholders on election threats are unprecedented."

Intelligence is a business of many metaphors, however: It is not only the discipline of assembling a "mosaic" from many different bits of information, but often also an iceberg, of which only different portions are visible to different people.

So one big question in the remaining weeks before Election Day is: What else is below the water?

Layer cake

Here's yet another metaphor for this aspect of the spy game: a layer cake.

There's a layer of activity that is visible to all — the actions or comments of public figures, or statements made via official channels.

Then there's a clandestine layer that is usually visible only to another clandestine service: the work of spies being watched by other spies.

Counterintelligence officials watching Chinese intelligence activities in Houston, for example, knew the consulate was a base for efforts to steal intellectual property or recruit potential agents, Demers said — likely in the energy sector or biomedical research. Most nations use their diplomatic posts partly for this kind of intelligence work.

And there's at least a third layer about which the official statements raised questions: the work of spies who are operating without being detected. What, in short, do Demers, Evanina and their compatriots not know about what's targeting the United States?

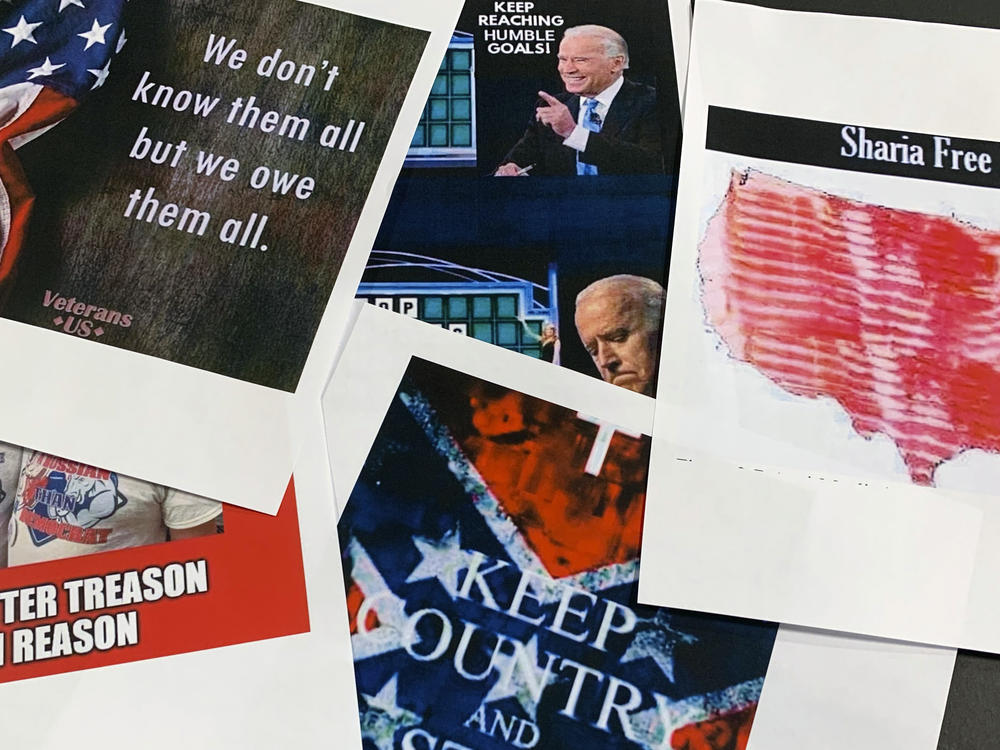

The challenges of election security include its incredible breadth — every county in the United States is a potential target — and vast depth, from the prospect of cyberattacks on voter systems, to the theft of information that can then be released to embarrass a target, to the ongoing and messy war on social media over disinformation and political agitation.

Is there more? From illicit financing to fraudulent documents to the presence of human provocateurs, the playbook for foreign interference has been developed over decades.

In the case of China, national security officials at every level never tire of warning about what they call the huge quantity of spying underway. Much of it, however, is old-fashioned espionage that seeks to steal intellectual property or government secrets.

The latest example: The National Counterintelligence and Security Center announced on Wednesday that it has been briefing U.S. government contracting officials about the risks associated with doing business with Chinese technology companies.

If Beijing is engaged in election interference, too, the question is what it may be doing outside the view of the public and unbeknownst to security officials.

Shifting battlespace

The state of play has changed in response to countermeasures imposed by the U.S. government, states, counties and social media platforms since 2016. Social media agitation, for example, became much more organic-seeming and more difficult to detect, according to one study.

And the avenues that attacking nations use for their messages have shifted, too, according to U.S. officials and the Big Tech platforms.

Witnesses have told Congress that when Facebook and Twitter made it more difficult to create and use fake accounts to spread disinformation and amplify controversy, Russia and China began to rely more on open channels.

They use self-styled news organizations such as Russia's RT or Sputnik, or they use open accounts linked with government officials, such as representatives for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

China's use of English-language messaging in particular has evolved significantly over the past year, according to specialists, especially in response to American rhetoric about the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2016, Russian influencemongers posed as fake Americans and engaged with them as though they were responding to the same election alongside one another. Russian operatives even used Facebook to organize real-world campaign events across the United States.

But RT's account on Twitter or China's foreign ministry representatives aren't pretending to do anything but serve as voices for Moscow or Beijing. If that work has become more overt, though, what else is still happening covertly — as Demers suggested about the Chinese government in Texas?

Critics: false equivalence

Detecting election interference relies heavily on foreign intelligence work, which means Evanina, Demers, Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe and their colleagues hold nearly all the cards when talking about it.

The members of Congress who see more of what the intelligence community collects on these subjects are circumscribed in what they can discuss openly because so much of the information is secret.

But lawmakers also complicate Americans' impressions about what is truly taking place because they attack one another over the ways they discuss secret material while seldom delving into its substance.

Democrats, for example, demanded a briefing from the FBI about the prospect that Congress might be the target of foreign efforts. Republicans responded with complaints that the rhetoric surrounding those demands was overblown. The point is to defend the U.S. and inform voters, they argued.

"Your use of this issue to knowingly and recklessly promote false narratives for political purposes is completely contrary to that goal," wrote Sens. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., and Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, to Democrats after their initial announcement.

The divergence didn't end after Evanina's statement, which described the election-interference ambitions of China, Russia and Iran. Democrats called that a distortion, arguing that the importance of the work by Russia far outweighs the other two powers.

"Unfortunately, today's statement still treats three actors of differing intent and capability as equal threats to our democratic elections," said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif.

The Democrats said they wanted the public "to be provided with specific information that would allow voters to appraise for themselves the respective threats posed by these foreign actors, and distinguish these actors' different and unequal aims, current actions, and capabilities."

So far the intelligence community hasn't complied, but the government has sought to send the message that it's taking the issue seriously in another way — with the offer of a $10 million bounty for information about threats to the election.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content