Section Branding

Header Content

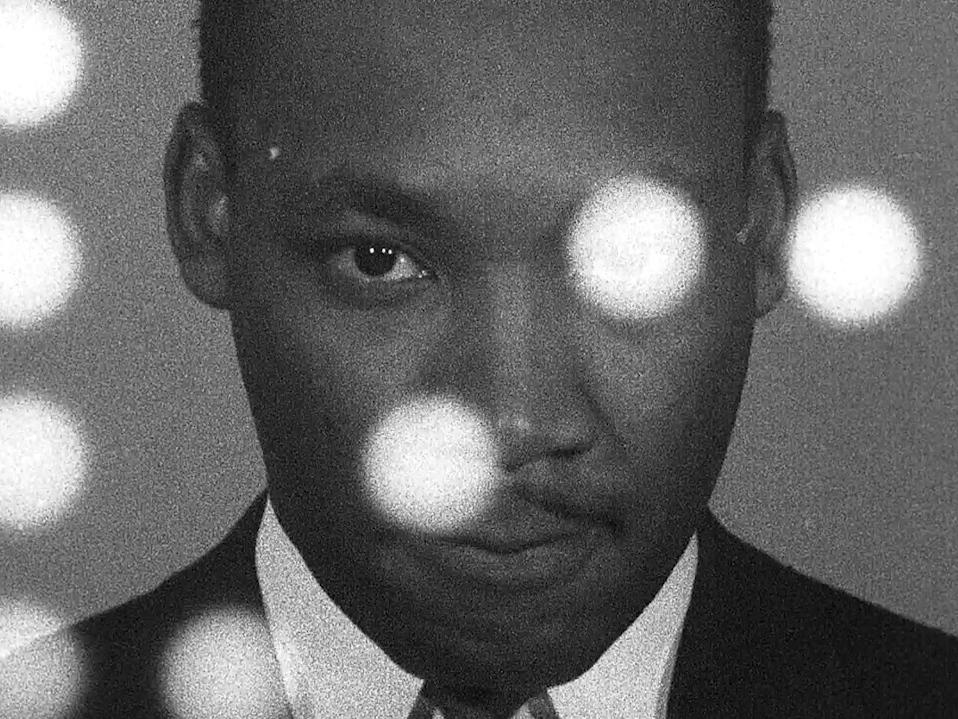

'MLK/FBI' Humanizes A Civil Rights Icon's Legacy

Primary Content

A year ago the official Twitter account of the Federal Bureau of Investigation tweeted, "Today, the FBI honors the life and work of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr." It was accompanied by a photo of the FBI Academy's reflecting pool, where a quote from King is etched in stone: "The time is always right to do what is right."

This wasn't the first time the FBI sent out a statement honoring the slain civil rights leader on the holiday that bears his name, and the responses to the ostensible hypocrisy of it all were no less colorful than they had been in previous years: expletive-filled kiss-offs, angry memes, and links or screenshots from articles detailing the agency's notoriously relentless surveillance of King in the final years of his life. Few took the FBI's "honor" seriously, because why would they? In the 1960s, the organization, led by its director J. Edgar Hoover, made active attempts to dismantle King's work and influence.

This is neither new nor little-known information, but that doesn't render Sam Pollard's documentary MLK/FBI, now streaming on demand, less essential. Working with recently declassified documents from the National Archives which reveal a deeper sense as to the extent and insidiousness of the agency's surveillance, the film aims to restore dimensions to the now-flattened image of King, who today is often reduced to iconography and erroneously viewed by many as having been a noncontroversial figure during his lifetime.

And like Ava DuVernay's Selma, a dramatization with similar aims, it succeeds: Pollard and his team – which includes writers Benjamin Hedin (also the producer) and Laura Tomaselli (also the editor), as well as archival producer Brian Becker – craft an immersive historical play-by-play of how and why King became a target for Hoover and his cohort, placing the activist firmly in context within the era.

Interviews with various scholars, former FBI officials like James Comey, and King's close friends and confidants play out primarily in voice-over (we see no talking heads until the film's final minutes), which allows the filmmakers to be creative in their visual storytelling. In addition to Becker's uncovering of rare news clips and footage of King with his family, an effective narrative choice is in the frequent use of excerpts from movies like I Was a Communist for the FBI and The FBI Story. Beverly Gage, author of G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the American Century, tracks the making of the myth of the FBI as a heroic, moral institution, one driven in large part by the plethora of pro-FBI content in media and entertainment.

As MLK/FBI explains, it's King's association with Stanley Levison, a progressive lawyer and businessman with Communist Party ties, that initially caught the attention of Hoover. But it was his growing impact on the international stage (the Nobel Peace Prize award in 1964; the "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington in 1963), as well as the discovery of his extramarital affairs, which kicked the FBI's espionage of King into high gear, manifesting into a years-long obsession. The filmmakers don't shy away from the more unsavory details – including a potentially unreliable FBI document suggesting King was present during the sexual assault of a woman by another man – instead engaging with them head on, as interviewees make the strong case for viewing the investigation as one driven by the deeply ingrained perception of black men as inherent sexual deviants.

Recurring themes arise. On a federal judge's order, the surveillance tapes of King are sealed in the National Archives until at least 2027, and ethical questions are posed about whether dissecting these details are yet another invasion of King's privacy. There are cautions against taking the content of the documents at face value, because of the inherent racial biases and at-times dubious methods of their authors. And of course, there's the concern over King's legacy and how it might crack under revelations that seemingly contradict his near-deified memory.

These are valid issues worth wrestling with. But Pollard and his collaborators seem to know and trust that there is more to be gained from this exercise than lost. And as Clarence Jones, a speechwriter for King, puts it, "Does [the truth of his romantic dalliances] make him in my mind less of an historic civil rights leader? No, it does not."

Such an engagement with one of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century has been long overdue. A common schtick among those decrying Black Lives Matter "rioters" is to compare the activists and their supporters unfavorably to King and the civil rights movement. The modern-day tactics for protest and activism – say, taking a knee or calling for the removal of Confederate monuments – are the "wrong way" and are only sowing further division, they suggest, while King knew how to demonstrate "right."

They willfully ignore the facts of the FBI's insidious infiltration of King's inner circle, and the marking of him at one point as "the most dangerous Negro" in the country by one of the agency's top officials. They evade the truth of his outspokenness against United States involvement in the Vietnam War at a time when it was politically dangerous to take such a position, leading even more people to turn against him toward the end. At one point in the documentary, Gage cites a public opinion poll taken after Hoover and King engaged in a public spat – 50 percent of respondents at the time sided with Hoover, and only 15-20 percent agreed with King. These reactions, and many more, all directed at the man (and movement) who advocated for many of the same things BLM is pushing for today.

King's legacy is complicated, but certainly not undone, by MLK/FBI. That's a good thing; the more we see him as an extraordinary but flawed human being, the easier it is to envision a path forward.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.