Section Branding

Header Content

New Effort To Clean Up Space Junk Reaches Orbit

Primary Content

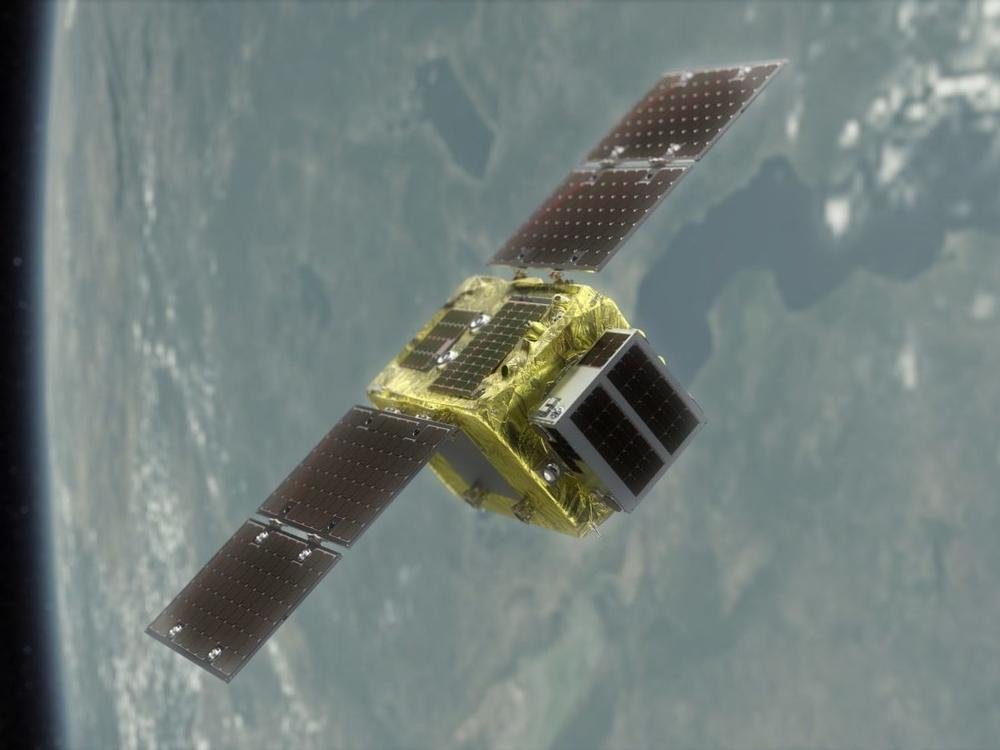

A demonstration mission to test an idea to clean up space debris launched Monday morning local time from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Known as ELSA-d, the mission will exhibit technology that could help capture space junk, the millions of pieces of orbital debris that float above Earth.

The more than 8,000 metric tons of debris threaten the loss of services we rely on for Earth-bound life, including weather forecasting, telecommunications and GPS systems.

The spacecraft works by attempting to attach itself to dead satellites and pushing them toward Earth to burn up in the atmosphere.

ELSA-d, which stands for End-of-Life Services by Astroscale, will be carried out by a "servicer satellite" and a "client satellite" that launched together, according to Astroscale, the Japan-based company behind the mission. Using a magnetic docking technology, the servicer will release and try to "rendezvous" with the client, which will act as a mock piece of space junk.

The mission, which will be run from the U.K., will carry out this catch and release process repeatedly over the course of six months. The goal is to prove the servicer satellite's ability to track down and dock with its target in varying levels of complexity.

The spacecraft is not designed to capture dead satellites already in orbit, but rather future satellites that would be launched with compatible docking plates on them.

Space junk has been a growing problem for years as human-made objects such as old satellites and spacecraft parts build up in low Earth orbit until they decay, deorbit, explode or collide with other objects, fragmenting into smaller pieces of waste.

In 2019, for example, India blew apart one of its satellites orbiting Earth, creating hundreds of pieces of debris that threatened to collide with the International Space Station.

According to a recent report by NASA, at least 26,000 of the millions of pieces of space junk are the size of a softball. Orbiting along at 17,500 mph, they could "destroy a satellite on impact." More than 500,000 pieces are a "mission-ending threat" because of their ability to impact protective systems, fuel tanks and spacecraft cabins.

And the most common debris, more than 100 million pieces, is the size of a grain of salt and could puncture a spacesuit, "amplifying the risk of catastrophic collisions to spacecraft and crew," the report said.

According to NASA, cleaning up space — and addressing the risks associated with debris — depend on preventing the accumulation of more waste and actively removing it.

The development of other cleanup technologies has been underway for years. In 2016, Japan's space agency sent a 700-meter tether into space to try to slow down and redirect space junk. In 2018, a device called RemoveDebris successfully cast a net around a dummy satellite.

The European Space Agency also plans to send a self-destructing robot into orbit in 2025, which the organization's former director general has referred to as a space "vacuum cleaner."

These efforts could prove increasingly important as private space ventures like SpaceX continue to clutter low Earth orbit with a "mega-constellation" of satellites.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.