Section Branding

Header Content

In China, Atlanta Shooting Victim's Kin Struggle To Understand Her — And Her Death

Primary Content

ZHUHAI, China — Feng Daoyou loved her family, even if she never heeded their advice much.

"Marry someone, anyone," her older brother, Feng Daokun, remembers telling her for years. "We kept at it, called her a spinster. She got mad at that."

Feng preferred independence. Then, a few years ago, as her extended family's main breadwinner, she began building a new dream — a new house for her clan of loved ones in China.

That dream ended violently, when Feng, 44, was shot to death in a Georgia spa on March 16. She was one of four people killed at Young's Asian Massage, and one of six women of Asian descent who were killed in the series of attacks that day. The 21-year old man arrested in the shootings has been charged with eight counts of murder.

Feng, who'd lived in the U.S. for about five years, died a stranger in a strange land. She was the only victim with no next of kin or close friends in the U.S. who could claim her body. People whom she'd never met volunteered to organize and attend her funeral.

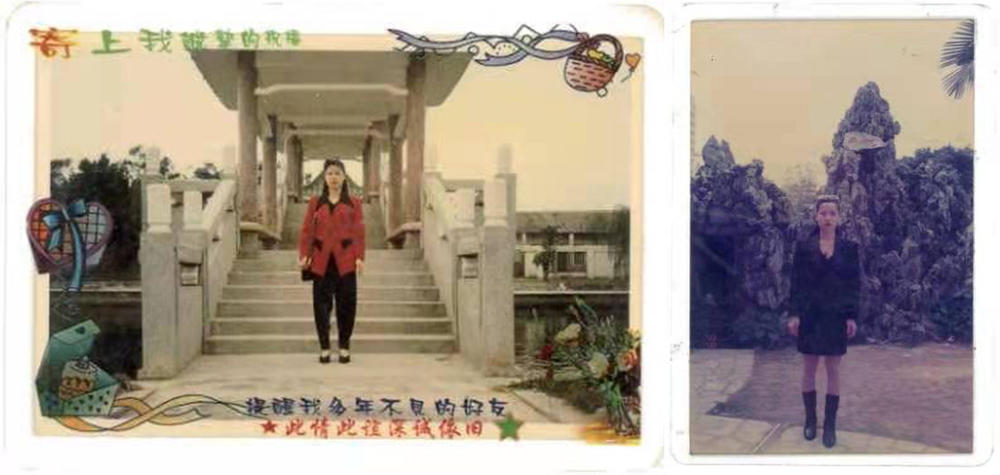

In death, Feng remains a mystery, even to her family in southern China. They remember her as an outgoing daughter, aunt and sister. But unlike them, she never married and never had children, though she gave generously to her nieces and nephews every lunar new year.

She seemed to relish venturing far from home. She spoke so directly and loudly her family sometimes thought she should have been born a man.

"She could do anything she put her mind to. She was tough. She never gave up. That was just her personality," remembers Daokun, her brother, who works the night shift as a security guard in the city of Zhuhai in Guangdong province.

The youngest of four children, Feng Daoyou was born in a village outside Lianjiang, another city in the province.

She dropped out of middle school for work. Feng's father had died when she was young, and the school fees were more than her oldest brother, Daokun, then newly married, could comfortably afford.

Better start working and find a husband, he and another brother advised her.

She did the former. In the early 1990s, China was on its way to becoming the factory of the world. As internal restrictions on movement loosened, hundreds of millions of rural residents left their fields and streamed into urban factories along China's east coast.

A teenage Feng was one of them. She left her hometown for Shenzhen, where she worked briefly in an electronics component factory. When she found the work too tiring, she became certified as a beautician. She moved to Shanghai and worked for several years in a salon there.

She'd long had ambitions of moving to the U.S. A friend whom she'd met in the Shanghai salon had already moved there. Feng wanted to follow in her footsteps.

But family came first. In 2015, Feng moved to Guangdong's Zhanjiang city to care for her other brother, who had become chronically ill. He died early the following year.

Feng began talking again about finding work in the U.S.

"We all thought she was joking," Daokun recalls with a chuckle. "How does someone who didn't even finish middle school find her way to America?"

When he received a call in April 2016 from a phone number he didn't recognize, he didn't pick up. Then a text arrived from the same number — a U.S. number.

It was from Feng.

"That was when I believed her," says Daokun.

Without telling her family, Feng had gone to Hong Kong, and from there made her way to the U.S. NPR was not able to determine how she entered the U.S. from Hong Kong. Based on the Chinese passport information her brother provided NPR, the Department of Homeland Security has no record of Feng entering or exiting the U.S.

Within a month of calling her brother, Feng told him she'd found a job as a beautician. Soon she found a second job, putting in back-to-back, 15-hour work days. She began bulk-buying groceries to save time. Daokun says his sister was impressed at how cheap shrimp and rotisserie chicken were in the U.S.

Eventually, she saved enough to buy a used car, moving cities every few months for work. Throughout, she sent money home to support her mother's living expenses in China.

But her brother urged her to come back home soon.

"For poor people like us, being busy is good, as long as we stay close to home and stay out of harm's way," says Daokun.

The last call his sister made to him was on March 15, the day before she was killed.

"She talked about sending money to us for Qingming, the tomb-sweeping holiday, which was coming up. Every year we would visit our ancestral tombs. She specifically told me to ask our ancestors for protection so that she could get her U.S. green card and that she could be safe from harm," remembers Daokun.

After Feng died, volunteers offered to ship her ashes back to her hometown in China. Her family refused.

"Our custom is that an unmarried woman's remains cannot enter her home village," explains Daokun. "We had nowhere to bury her."

Instead, Feng was buried near where she was killed. A local volunteer group, the Atlanta Chinese American Alliance, arranged a funeral. Nearly 100 people attended, said Dr. Charles Li, the funeral organizer.

And so Feng Daoyou now rests in a cemetery just outside Atlanta, in Norcross, Georgia. She was headstrong, beautiful, hardworking. She left behind nearly zero possessions, no known close friends — and difficult questions for her anguished family.

Her brother wants to understand why she was targeted and how her killer might be brought to justice. He wonders how to guide their family in her absence.

He says he has not told their 82-year-old mother her daughter is dead, fearing for her health. The house Feng was funding will be finished this October, but he does not know how he will finish paying off the remaining mortgage.

He hopes to visit his sister's grave in Atlanta someday. But he says he's scared to go.

Amy Cheng contributed research from Zhuhai, China.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.