Section Branding

Header Content

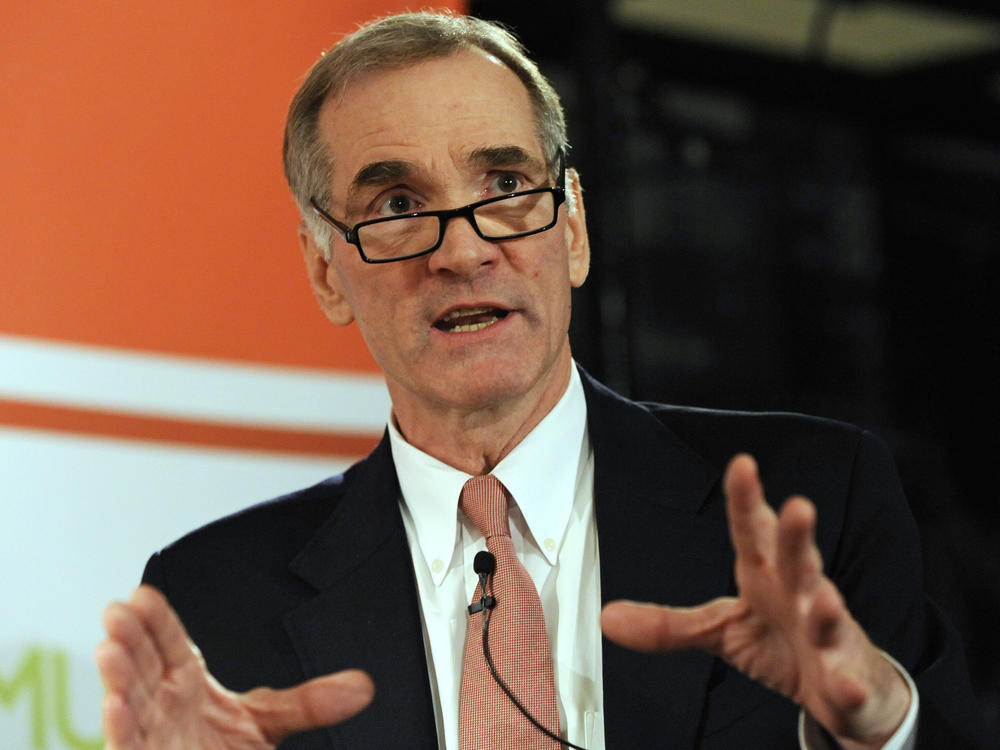

David Swensen, The Greatest Investor You Maybe Never Heard Of, Leaves Powerful Legacy

Primary Content

A pioneering investor who ran Yale University's endowment, David Swensen, died this week at the age of 67 after a years-long battle with cancer. Swensen revolutionized the way many colleges invest, infusing some schools and nonprofits with vastly more resources to pay for things like financial aid for students and research.

Swensen was widely regarded by other investors as one of the greatest in the world. Case in point: He grew Yale's endowment from $1 billion in 1985 to $31 billion last year.

But he's not a household name. And that's maybe because he didn't make those billions for himself — even though, with his track record, he almost certainly could have if he'd started his own hedge fund.

Instead, after an early career on Wall Street, Swensen came back to Yale, where he'd gotten his PhD in economics. He took charge of the university's investments and stayed there for the rest of his life.

"And look, I had a great time on Wall Street," Swensen told NPR in 2006. "But it didn't satisfy my soul."

Swensen instead wanted to make money with more of a sense of mission around it. "I've always loved educational institutions," he said. "My father was a university professor. My grandfather was a university professor."

On the side, Swensen taught a popular class about investing at Yale for decades. (He was teaching a mere two days before he died.) He came across to people less like a titan of investing and more like a very likeable high school or college math teacher.

But pretty soon, this unassuming man was revolutionizing the way universities invest their money.

Instead of buying just a simple mix of stocks and bonds, Swensen sought out the very best boutique investment outfits, and through them, invested in all kinds of things: real estate, timber, shampoo and soap companies in Asia. He put seed money into technology startup companies.

His great insight was that — if done right — an endowment made more money with less risk by hiring very talented money managers to invest in many different types of assets.

Basically, he built a table with 10 legs: very stable even if a few legs get wobbly or fall off.

"He was incredibly important to me personally," says Tom Steyer, the billionaire investor who recently ran for president. Steyer says that early in his career, Swensen invested through his hedge fund — which was a big deal. As Swensen gained respect in the investing world, it was a stamp of approval if he chose a particular hedge fund to manage some of Yale's variety of investments.

"What David did was he pioneered new ways of thinking about investment," says Steyer. "He did it with absolute integrity and honor. And he did it for a bigger cause than himself; he did it to try and further higher education in the United States of America."

Swensen also became known for finding new talent; sometimes, that meant people who didn't even have a background in finance.

"I was an art conservator working for museums," says Paula Volent, who was studying at the Yale School of Management when she asked Swensen for a campus job — just filing paperwork at the investment office.

Volent wanted to learn a bit about endowments because she wanted to run a museum someday.

"I went knocking on his door and he took me in," Volent says. She says Swensen was a good teacher and soon started giving her more and more responsibility.

Today, she's the chief investment officer at Bowdoin College.

"He was so passionate about investing, it was contagious, you know, and it was so interesting to work there," says Volent. And she says Swensen encouraged her and other women to work in the male-dominated world of investing and finance.

"David was the person that he never had any doubts that you could do it," she says. "And a lot of times he would push you to do things and to be excellent."

A few years ago, Volent's endowment at Bowdoin beat Yale's 10-year return, which Swensen definitely noticed.

"He wrote me this letter, it's sort of personal," Volent says as she pulls the framed letter off her wall.

"It says, 'Congratulations Paula — poor is the pupil who does not surpass the teacher,' which is a quote from Leonardo da Vinci."

Volent's not the only pupil who's done well. Swensen's proteges have gone on to run endowments at many other schools and non-profits. Volent says they're sometimes called the Yale mafia. (But, like, the nice mafia.)

Swensen also wrote a book, Unconventional Success, telling everyday people how to invest and avoid pitfalls like excessive fees charged by mutual funds.

Swensen talked in the book about how ordinary people often can't get into the types of investments that he did with Yale's endowments; the fee structures offered to them are just too high and too out of line with investors interests.

"He would be the first one to say that the Yale model that he started for investments isn't for everyone," Volent says. "He was the pioneer in getting alternative investments, venture capital, hedge funds, things like that, into institutional portfolios."

But Volent says, "it was sort of 'don't do this at home.'" She says that individual investors can't invest this way. And even colleges, pension funds and nonprofits need to have an accomplished staff and expertise to be able to do it successfully.

Part of that has to do with knowing how to pick really good people to invest with. Another has to do with the fees.

When it came to individual investors, for example, Swensen was a harsh critic of how the vast majority of big actively managed mutual funds offer lower returns than simple lower-cost index funds, after fees are factored in. And the mutual funds make huge amounts of money whether the fund performs well or not.

Conversely, for institutional investors with the clout and expertise, Volent says Swensen believed very strongly there was a place for active management by investing with "smaller firms, boutique type firms where when the manager makes money, you make money. And when you lose money, the manager loses money."

As a person, Volent says Swensen was also just fun to be around and work with. He got everyone to play on the office softball team. And when they'd be up all night doing a big mailing, he'd often show up with a keg of beer.

"He just loved being around people," she says. "He's going to be sorely missed."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.