Section Branding

Header Content

He Lost Nearly Everything To Addiction. Then An Arrest Changed His Life

Primary Content

Heroin started rewiring and taking control of Will's brain in the early 2000s, as he turned 40.

"Back then, if you used drugs people didn't want anything to do with you," Will recalls. "People gave up on me."

Will lost almost everything: jobs, his driver's license, his car, his marriage and his home. He found enough temporary work to pay rent on a room, ate at soup kitchens, and stole and resold goods for cash.

"Feeding that addiction," he says. "Feeding that monster."

We're only using Will's first name because future landlords or employers might not take him based on his record.

The game changer

One morning almost three years ago, with no heroin and no money to buy any, Will went into withdrawal. This former basketball player, once in top shape, dragged himself down the street searching for a deal. He had some crack that he could sell. The buyer was an undercover cop.

"That was the game changer," Will says.

Instead of prison, Will was sent to a daily probation program in Massachusetts called Community Corrections. It's one sign of what has changed in the 50 years since President Richard Nixon declared the War on Drugs. It ended up targeting people with Black or brown skin, like Will.

"In the early 1970s when this so-called War on Drugs was started, it really functioned much more as a war on the people addicted to drugs," says Dr. Stephen Taylor, an addiction psychiatrist in Birmingham, Ala.

The Massachusetts program launched 25 years ago as a remedy for prison overcrowding. But attitudes about drug users were beginning to shift too.

"There was a pivot toward this idea of substance use disorder as a disease rather than merely some kind of a lack of willpower," says Vin Lorenti, director of community corrections for the Massachusetts Probation Service.

From 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday, Will was required to participate in counseling and other elements of addiction treatment. He had classes on anger management, problem-solving and job training.

Massachusetts has 18 such centers. Today, three-quarters of people sent to community corrections in Massachusetts have a history of drug use. Since they live at home the cost is a fraction of incarceration. And only about half the people in this program reoffend, compared with those leaving prison.

Gaps and disparities

Marc Levin with the Council on Criminal Justice says most states have an alternative path for drug users charged with minor offenses. There are police departments that offer immediate placement in addiction treatment, drug courts and other community-based options such as the one Will entered. But while some drug users are offered treatment instead of punishment for petty crimes, Levin says, others are still sent to jail.

"We really have to hit the accelerator when it comes to these alternatives," says Levin, who directs policy for the council. "They are on the books across the country, but when you actually look at the utilization, particularly in rural areas, that's where you really see gaps and disparities."

Lorenti says the War on Drugs still casts a shadow over programs that direct drug offenders to treatment.

"Some people might think 'oh, well that's being soft with crime,'" Lorenti says. "But if you know somebody that's struggled with substance use disorder, you know that pursuing your recovery is not something easy or soft."

Will came out of community corrections trained for a job that aims to help drug users through that struggle. He's a recovery coach. Will walks the streets where he used to buy drugs, distributing Narcan and flyers about safe drug use, helping people get into a detox program, taking clients to AA meetings and connecting them with lawyers or medical care if needed.

"It's an everyday battle and challenge," Will says, "but it's gratifying."

Treated and controlled

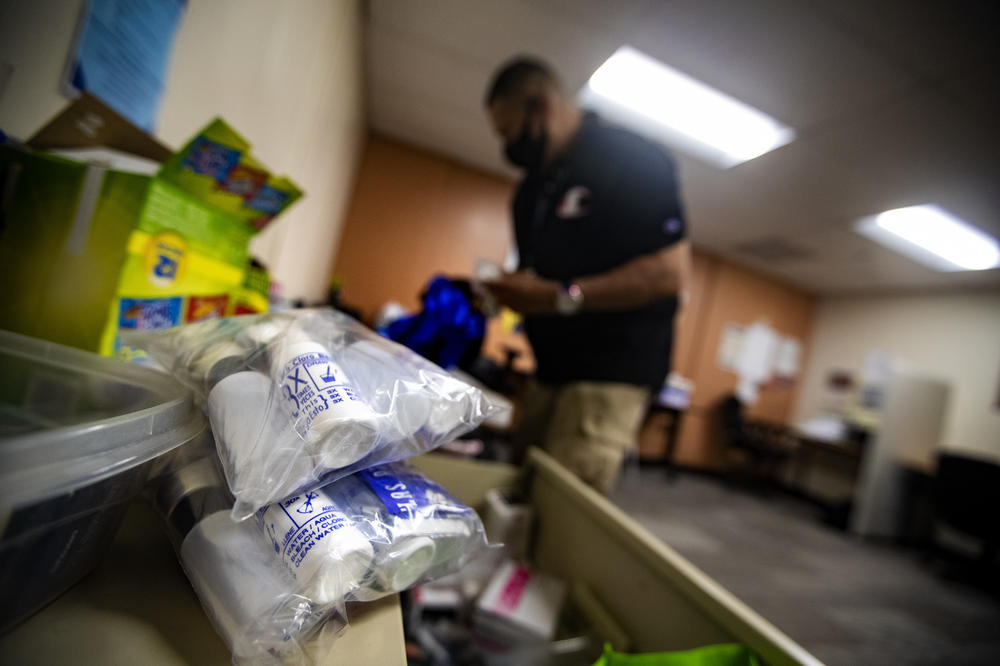

Will works out of an office at the Lynn Community Health Center north of Boston. It's piled with donated clothing, shoes, diapers, backpacks and toiletries. There are drawers of condoms — and syringes. Providing clean drug supplies is still illegal in some communities but is encouraged by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Dr. Kiame Mahaniah, the health center's CEO, hired his first recovery coaches just a few years ago, paying for them with grants.

"It's very recent that people with lived experience are valued as the most important member of the team because of that lived experience," he says. "Now it's just unimaginable to think that we'd be able to do the work without recovery coaches."

And medications are transforming treatment for those like Will who are addicted to opioids.

"Addiction can be treated and controlled," says Taylor, who is a member of the American Society of Addiction Medicine board. "The outcomes when we provide people with treatment for addiction are roughly similar to the outcomes for people who are treated for other chronic medical conditions."

Many studies prove that drugs prescribed to treat an addiction to opioids prevent overdoses and save lives. Mahaniah credits these meds with relieving the symptoms of addiction so that patients can focus on rebuilding their lives.

"Compared to 40 years ago, the difference in the landscape is amazing," he says.

"The sky's the limit"

Will takes methadone, the oldest of the three approved medications. He has to go to a designated methadone clinic to get his dose. Will says he still feels dismissed by some people who see him there or know he used heroin for many years.

"A lot of people are very judgmental," he says. "They like to say, 'That person's not going to amount to nothing.' If you don't give somebody a chance, how are they going to make it in life?"

Will, now 56, says he's grateful for the people who did take a chance on him — and for his church, which he calls the foundation of his two years in recovery. He is tapering off methadone and plans to continue recovery without it by summer's end. He bought a car. And he's signed up for classes this fall, more training in addiction recovery so he can help others return to healthy, productive lives.

"I feel happy about where I am now," he says. "I just pray to God that I can keep doing this for a while. The sky's the limit."

Copyright 2021 WBUR. To see more, visit WBUR.