Section Branding

Header Content

Christmas Eve telescope launch has astronomers hoping for good tidings of great joy

Primary Content

A churning mix of excitement and anxious dread has taken hold of astronomers around the world as they wait for the launch of the most powerful telescope ever, planned for the morning of Christmas Eve.

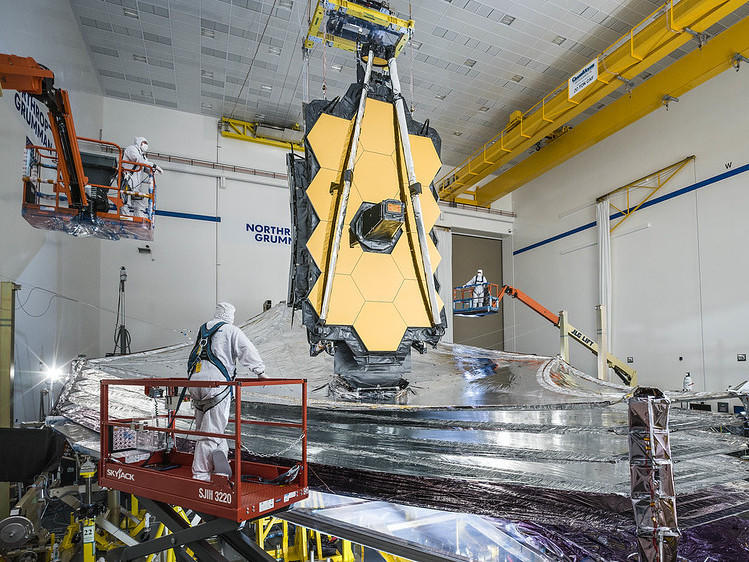

The James Webb Space Telescope has been in the works for decades, and its gold-plated, 21-foot mirror will see much farther out into space than the venerable Hubble Space Telescope. Its launch has been delayed so many times over the years that, for many, it seems almost unbelievable that it's finally about to happen.

Someone on Twitter even joked that anyone nervous about the James Webb Space Telescope colliding with Santa during liftoff should relax because "James Webb launching is just a story we tell children, it's not real."

As surreal as it may seem, the 7-ton, once-in-a-generation scientific instrument named after a former NASA administrator is in fact now at a launch site in French Guiana, almost ready to go. Jackie Faherty, an astrophysicist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, says that every time the impending launch pops into her head, her stomach turns.

"I am so nervous! And excited," says Faherty, noting that on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being maximum terror, she's currently at 6 in terms of her baseline anxiety level. "Then when I really think of it, I feel like I pop up to like an 8, where I am like, 'How are we going to do this? What's going to happen?'"

Asked about coping strategies, one astronomer quipped, "Does wine count?"

The three-story-tall telescope, with its heat shield the size of a tennis court, is all folded up and crammed inside a rocket. It will have to unfold itself and travel about a million miles away from Earth, cooling down to temperatures around minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit.

Before all that can happen, it has to get safely off the planet. Astronomers can't help but imagine this $10 billion telescope getting obliterated in an instant by an unlikely, but still possible, rocket explosion. But Faherty, who will be using the telescope for her research, thinks her anxiety will actually lessen on launch day.

"On launch day, I would say it's going to turn into that feeling of watching a historic moment, of being a part of a historic moment," Faherty says. "We're launching this amazing engineering feat into the cosmos."

If liftoff goes well, astronomers' brief celebration will once again turn to nervous waiting as the telescope slowly unfurls itself over days and weeks.

"We'll have our 29 days of terror as we're watching things being deployed," says astronomer Garth Illingworth of the University of California, Santa Cruz. "That first month is going to be rough."

Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, this one can't be repaired by astronauts because it will be too far away. And NASA isn't exactly playing down the fact that this time there are no second chances. The agency put out a video titled "29 Days on the Edge" that runs through all of the different little bits that could malfunction.

"I think the first few minutes of the launch will be the most worrisome as there is nothing to be done if something goes wrong, but a close second is the unfolding of the mirror," astronomer Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science told NPR in an email.

"I have images in my head of a half-unfolded mirror stuck in place, which would be very bad, something like what happened to the Galileo spacecraft with its main antenna getting stuck during the fold out process," said Sheppard. "Anytime you have a moving part that needs to unfold, it is a worry as the launch is a very violent event that could damage a mechanical device and not allow it to work properly when needed."

Still, if all goes well, this telescope should transform astronomy. Sheppard, for example, is looking forward to the chance to learn more about distant planets that orbit faraway stars. Other researchers can't wait to capture light from some of the first galaxies to form in the universe.

And even as they anxiously wait, some astronomers philosophically ready themselves to accept whatever comes.

"Look, it can fail, and from history we know that you have to dare to dream," says Priyamvada Natarajan, an astronomer at Yale University who wants to use this telescope to study black holes. She adds that the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has changed her perspective and made her far less worried about any losses that don't involve human lives.

"I'm very excited, slightly tense, but I really think we can pull this off," says Natarajan. "I totally trust that we've done the best that we can. Let's just hope it all unfolds."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.