Section Branding

Header Content

Trump and his lawyers keep ghosts of Nixon and Watergate alive and haunting

Primary Content

The building drama over documents that left the White House with President Trump provides fresh proof that the ghosts of old scandals never die – or at least not in Washington.

Watergate happened half a century ago, but its name and spirit are still with us, thanks in large measure to former President Donald Trump. He has not been charged and may never be charged, but memories of President Richard Nixon have been revived repeatedly by two impeachment proceedings and countless other scrapes and potential scandals. Trump has found himself at odds with Congress, federal courts and legal authorities in at least two states.

And yet it is the document dispute, which has been public since the FBI searched and seized documents at Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida on Aug. 8, that brings the specter of Watergate to the fore with renewed force.

Operatives hired with money from Nixon's 1972 re-election campaign were caught burglarizing and bugging the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate office complex. Fearful of the fallout, Nixon ordered aides to cover up the connection and directed the payment of hush money to the burglars. Discussions of all this at the White House were caught on Nixon's own taping system, and two years later those recordings would force him to resign on the brink of impeachment and removal from office.

But along the way, when it mattered most, Nixon and his crew found that people who might have been political allies in the past were not especially sympathetic to his case.

"Be careful what you wish for..."

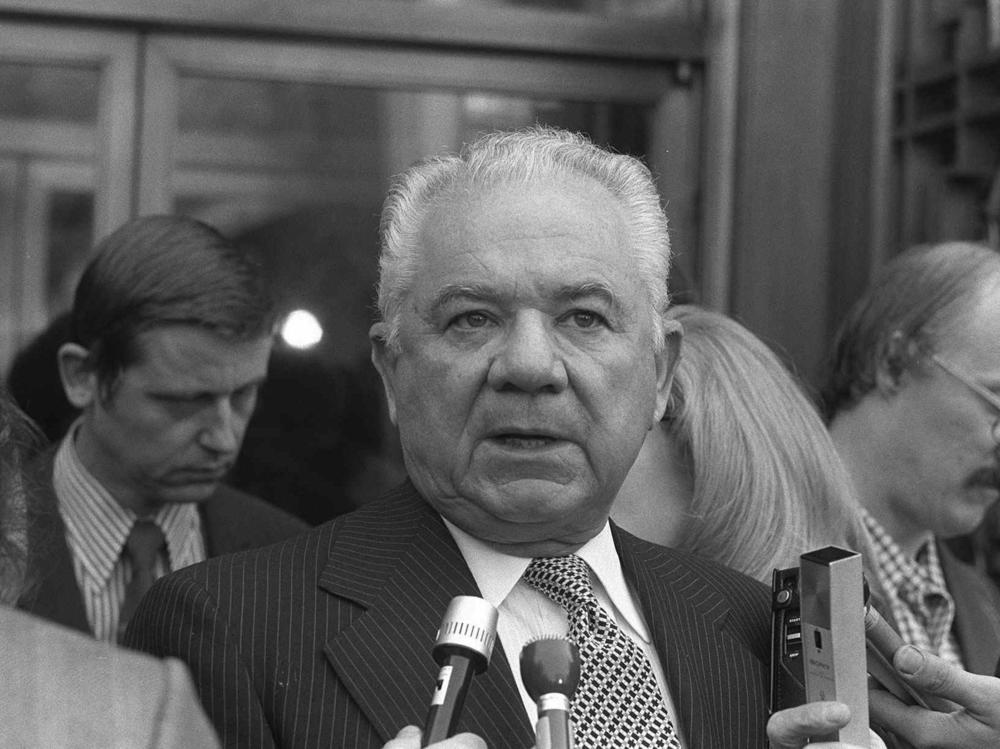

When Nixon fired Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor who had been pursuing him in the fall of 1973, the White House recruited a replacement who seemed likely to be more tractable. Leon Jaworski was a well-respected Texas prosecutor who had supported Nixon for president twice (and would later join a Texas-based group called "Democrats for Reagan"), Surely he would not be as dogged in seeking the White House tape recordings as Cox had been – or so people thought in the fall of 1973.

Wrong call. Jaworski proved a relentless pit bull as special prosecutor. He led a grand jury to indict nearly a score of White House personnel and name Nixon himself "an unindicted co-conspirator."

The Nixon team had also thought they might find a relatively friendly courtroom when Federal Judge John J. Sirica took over handling the Watergate cases and trials. A former congressional staffer for Republicans, Sirica had been active in the GOP and rewarded with a federal judgeship in 1957 by Republican Dwight Eisenhower, while Nixon was vice president.

By 1972, Sirica was the senior judge on the District of Columbia circuit and could assign cases as he pleased. He assigned Watergate to himself. But from there on, nothing went quite as Nixon's team might have hoped. Sirica sentenced the president's chief of staff and his top domestic adviser to prison terms, along with Nixon's first attorney general and his former White House counsel and others.

Sirica was responsible for the pivotal ruling that Nixon could not claim executive privilege to withhold the critical tape recordings Jaworksi wanted to use as evidence at criminal trials. Sirica eventually ruled that the tapes also had to go to the House Judiciary Committee as it weighed Nixon's impeachment.

When Nixon took that on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, Jaworksi presented the argument for Sirica's ruling and won a unanimous judgment (including the votes of three justices whom Nixon had appointed).

The tapes were released to Congress; and 16 days later, Nixon was gone.

Déjà vu all over again

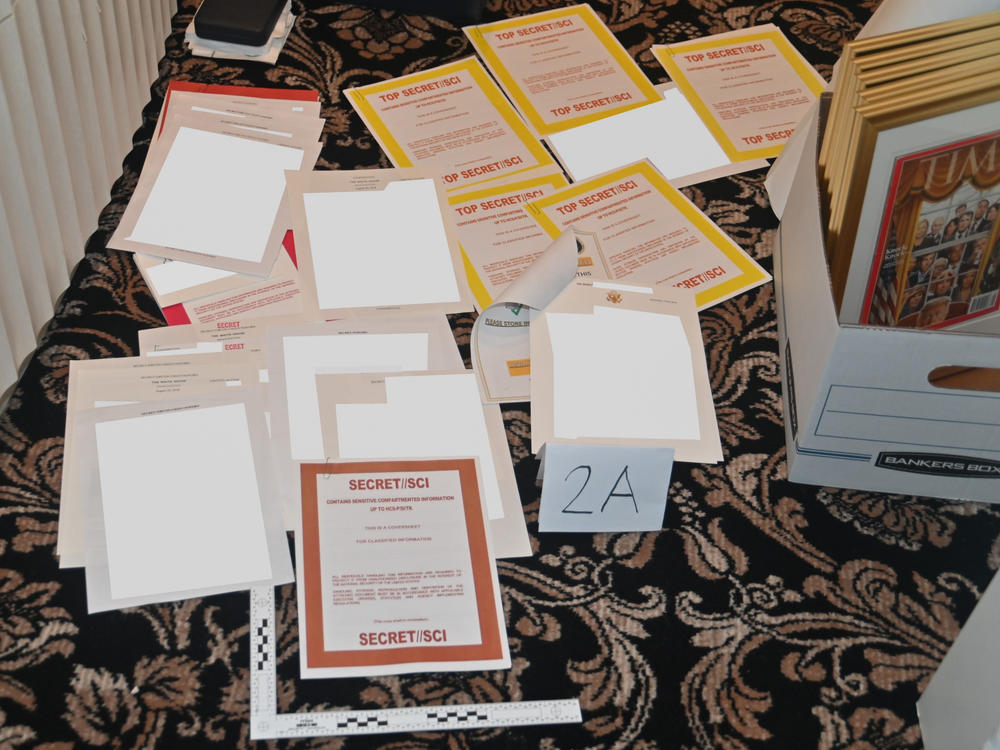

In recent days we have seen a beleaguered former President Trump struggling to find a legal response after an FBI search of his home that found scores of classified and even top-secret documents that his lawyers had told the authorities he no longer had.

Throughout his business and political careers, Trump has relied on the legal advice he got early on from one of his life mentors, the renowned attorney Roy Cohn. Having been the lead counsel for Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s and thereafter an attorney for prominent New Yorkers (including sports and entertainment celebrities and Mafia dons), Cohn had an approach to all disputes. "Don't tell me what the law is," he would say, "tell me who the judge is."

When Trump finally got his legal team together after the Mar-a-Lago search, they wanted a court to appoint a "special master" to review the documents and weigh Trump's claim to keeping them. The idea was to slow and possibly derail any plan to prosecute the former president.

But they did not go to the judge who issued the search warrant or to one of the other federal judges in the same courthouse, the closest federal court to Mar-a-Lago. Instead, they went 70 miles to the outer edge of the same judicial district, where they might have hoped to find a more receptive judge. There their case was assigned to Federal Judge Aileen Cannon, still in just her second year on the federal bench. Cannon was one of the last of Trump's appointees to be confirmed by the Senate.

She gave the Trump team most of what they wanted, including an order that the Department of Justice stop looking at the documents they had seized or using them in any way. She also ordered appointment of a special master, directing Justice and Trump's team to each suggest two candidates. Trump's team rejected both of Justice's candidates, but Justice was willing to accept one of the two names offered from the other side. That's the one Cannon chose.

But then things began to go awry. On Tuesday of this past week, the special master Cannon chose, Raymond Dearie, came to court in Brooklyn N.Y. and told the Trump team they needed to show evidence for Trump's claim that the documents had been declassified. Trump's lawyers said they wanted to hold any such evidence back for now, to leave the question open and then possibly use the declassification issue as a defense later on.

Dearie would not let them have it both ways. The documents were either classified or they were not. Put up or shut up, some might say. "You can't have your cake and eat it, too," Judge Dearie said.

Later in the week, things got even more problematic for Trump when a three-judge panel on the Federal Appeals Court for the 11th Circuit in Atlanta overruled Judge Cannon and said the Justice Department could continue using the classified documents in its investigation after all.

That panel included two of Trump's own appointees, and in their ruling they treated Cannon's previous ruling rather dismissively.

The 11th Circuit could be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, so we await the result there. But we have seen some of Trump's three appointees on that court vote against him as well during his fruitless objections to the 2020 election outcome.

The momentum of the case is decidedly not encouraging from the standpoint of the former president. And his own lawyers strongly implied to Judge Dearie that they foresaw Trump dealing with an indictment in the document case.

We are a long way from resolving this or several other legal matters pending against the former president. And the federal cases are unrelated to the proceedings in New York where the state attorney general has sued Trump and three of his adult children and the Trump Organization over fraudulent filings to deceive banks and tax authorities.

They are also unrelated to continuing testimony being taken by a grand jury in Georgia weighing charges against Trump for his attempt to overturn the 2020 election results in that state.

But as harvest time arrives, and as all these cases hover over the political season, one can sometimes hear echoes of "Watergate" wafting in the autumn breeze.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.