Section Branding

Header Content

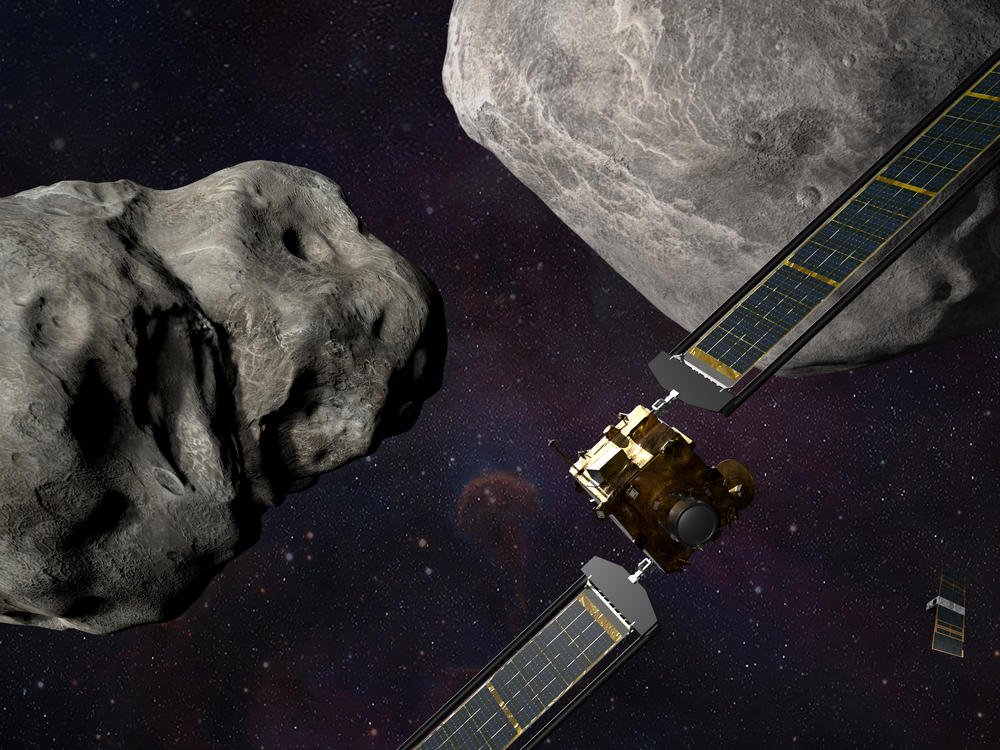

Move over, Bruce Willis: NASA crashed into an asteroid to test planetary defense

Primary Content

Updated September 26, 2022 at 9:07 PM ET

Nuclear bombs. That's the go-to answer for incoming space objects like asteroids and comets, as far as Hollywood is concerned. Movies like Deep Impact and Armageddon rely on nukes, delivered by stars like Bruce Willis, to save the world and deliver the drama.

But planetary defense experts say in reality, if astronomers spotted a dangerous incoming space rock, the safest and best answer might be something more subtle, like simply pushing it off course by ramming it with a small spacecraft.

That's just what NASA did on Monday evening, when a spacecraft headed straight into an asteroid, obliterating itself.

In images streamed as the impact neared, the egg-shaped asteroid, called Dimorphos, grew in size from a blip on screen to have its full rocky surface come quickly into focus before the signal went dead as the craft hit, right on target.

Events transpired exactly as engineers had planned, they said, with nothing going wrong. "As far as we can tell our first planetary defense test was a success," said Elena Adams, the mission systems engineer, who added that scientists looked on with "both terror and joy" as the spacecraft neared its final destination.

The impact was the culmination of NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), a 7-year and more than $300 million effort which launched a space vehicle in November of 2021 to perform humanity's first ever test of planetary defense technology.

It will be about two months, scientists said, before they will be able to determine if the impact was enough to drive the asteroid slightly off course.

"This really is about asteroid deflection, not disruption. This isn't going to blow up the asteroid," Nancy Chabot, the DART coordination lead at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, said earlier. She says the collision is just a nudge that's similar to "running a golf cart into the Great Pyramid."

Tweaking a space rock's orbit

Dimorphos is around 7 million miles away and poses no threat to Earth. It's about 525 feet across and orbits another, larger asteroid.

NASA officials stressed that there was no way their test could have turned either of these space rocks into a menace.

"There is no scenario in which one or the other body can become a threat to the Earth," says Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the science mission directorate at NASA. "It's just not scientifically possible, just because of momentum conservation and other things."

Instead, the impact should slightly shorten the time it takes for Dimorphos to orbit its bigger asteroid pal. Right now, a full circuit takes 11 hours and 55 minutes. The DART impact should change the path of Dimorphos so that it moves closer to the big asteroid and takes less time to go around, doing so perhaps once every 11 hours and 45 minutes.

These two asteroids are so far away that telescopes see them as a single point of light that dims and brightens as Dimorphos goes around. Images from the DART spacecraft's camera were the first chance that scientists had to see the asteroid they had been working to hit.

The spacecraft's onboard navigation systems initially targeted the larger and easier-to-spot asteroid, only switching their attention to Dimorphos in the last hour of the mission.

In the final minutes before impact at 14,000 miles per hour, NASA lost the ability to send commands to the spacecraft as scientists simply watched and waited. Cheers erupted in the control room as the screen went red from loss of signal.

A smaller spacecraft nearby was watching, and will send images back to Earth over the following days. Telescopes on all 7 continents, as well as space telescopes like James Webb, will also view the collision and its aftermath for weeks, making observations that will let astronomers precisely measure how the asteroid's path got altered.

What's more, in a couple of years, the European Space Agency will send a mission called Hera out to this double asteroid system, letting scientists gather even more information on the impact's effects.

All of this should reveal just how an asteroid reacts to a deliberate push, and scientists can take that information to help them make contingency plans to get ready for future threats.

"The bottom line is, it's a great thing," says Ed Lu, who serves as executive director of the Asteroid Institute, a program run by a nonprofit dedicated to planetary defense. "Someday, we are going to find an asteroid which has a high probability of hitting the Earth, and we are going to want to deflect it."

When that happens, says Lu, "we should have, in advance, some experience knowing that this would work."

Lots of asteroids have yet to be found and tracked

Still, the folks working on the DART mission seem to understand that their project can sound kind of far out.

"We're moving an asteroid. We are changing the motion of a natural celestial body in space. Humanity has never done that before," says Tom Statler, NASA's DART program scientist. "This is stuff of science fiction books and really corny episodes of Star Trek from when I was a kid, and now it's real. And that's kind of astonishing that we are actually doing that, and what that bodes for the future of what we can do."

NASA tracks lots of space rocks, especially the larger ones that could cause extinction-level events. Thankfully, none currently threaten Earth. But many asteroids the size of Dimorphos haven't yet been discovered, and those could potentially take out a city if they came crashing down.

That's why NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office wants to launch the asteroid-hunting space telescope NEO Surveyor, which could go up in 2026 or 2028, depending on how much money Congress allocates.

"It's something that we need to get done so that we know what's out there and know what's coming and have adequate time to prepare for it," says Lindley Johnson, NASA's Planetary Defense Officer.

He says such a telescope could give Earthlings years or decades or even centuries of warning about space rocks on an alarming path — plenty of time to come up with a solution, whether it's a "kinetic impactor" like DART or maybe another kind of spacecraft that would just fly next to a worrisome asteroid and use gravity to tug it gently away.

All of that is very different from the usual way that Hollywood portrays saving the planet, notes Johnson.

"They have to make it exciting, you know, we find the asteroid only 18 days before it's going to impact, and everybody runs around with their hair on fire," he says. "That's not the way to do planetary defense."

James Doubek contributed reporting.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.