Section Branding

Header Content

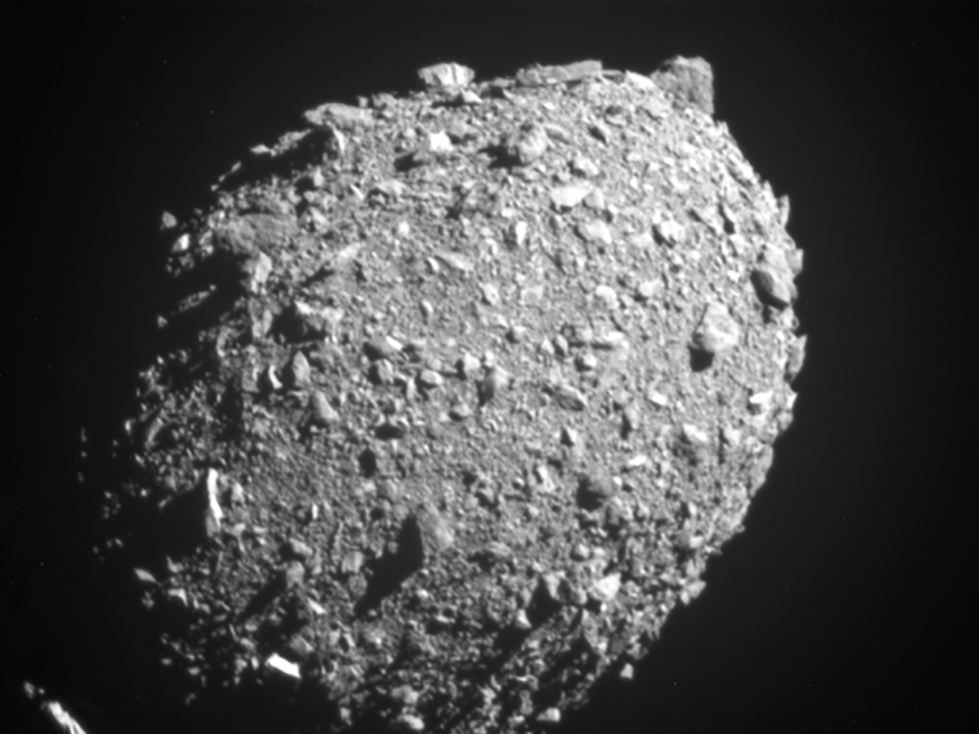

NASA says its asteroid defense test was a success

Primary Content

Updated October 11, 2022 at 6:17 PM ET

NASA says its mission to knock an asteroid off course — a test of planetary defense — succeeded beyond its expectations.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) slammed a spacecraft into one asteroid to see if it could change its orbit around another asteroid.

It did.

About 7 million miles away from Earth, the asteroid Dimorphos is in orbit around a larger asteroid called Didymos. It usually takes 11 hours 55 minutes for Dimorphos to make a complete orbit.

After the DART spacecraft made impact two weeks ago, that orbit has shortened to 11 hours, 23 minutes: a 32-minute change.

"This is a watershed moment for defense," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said on Tuesday. "This mission shows that NASA is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us."

The two asteroids pose no threat to Earth, but the test is proof of concept that if another asteroid does appear headed in Earth's direction, scientists have a way of pushing it off course.

A push for planetary defense

"For the first time ever, humanity has changed the orbit of a planetary body," said Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA.

The time was shortened by pushing Dimorphos, which has a diameter of about 525 feet, into a slightly closer orbit around Didymos. What pushed it closer was a combination of the kinetic force of the impact as well as the ejecta — dust and rock — that was blown off the asteroid's surface when the spacecraft hit.

Observers measured the time of the orbit by looking through telescopes in Chile and South Africa at the timing of when one asteroid eclipsed the other.

Visibility from Earth isn't great, so they were essentially looking at how often they saw "dips in brightness" from the area, according to Nancy Chabot, the DART coordination lead at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

Planetary radar facilities in California and West Virginia were also used to measure orbit times.

NASA initially predicted the orbit would be shortened by somewhere around 10 minutes, but estimates ranged from only a few minutes to "several tens of minutes," Glaze said, putting the 32-minute change in the upper range. The orbit time is accurate to within plus or minus two minutes, she said.

Now that the test has proved successful, if an asteroid one day threatens Earth, scientists should get to work years ahead of time, according to Glaze.

"We are capable of deflecting an asteroid," she said.

But the mission only caused a 4% change in orbit time, so "the more time we have for that little nudge ... the better off we are," Glaze added.

NASA expects to continue monitoring the asteroids through early next year. A European spacecraft is scheduled to arrive at the Didymos system in 2027 to investigate the asteroids in more detail.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.