Caption

Academy for Classical Education principal Laura Perkins (second from left) attends a recent meeting of the school's board.

Credit: Grant Blankenship / GPB News

Back in May, Macon Principal Laura Perkins brought some good news to the governing board of the charter school she runs.

“ACE has been named No. 1 middle and high school in Middle Georgia!” she enthused to murmurs of assent by the board.

ACE is short for the Academy for Classical Education. That declaration of “the best” was made by an online site based on standardized test scores and a school climate survey with five respondents.

A few years ago, the best school was exactly what Arnab and Garima Bannerjee were looking for.

“Brand new school came up, and all around everyone was talking, having, like, good reviews about the school,” Arnab Bannerjee remembered.

Back then, the Bannerjees, both of whom immigrated to the U.S. from India, were wondering how they would navigate the middle and high school years for their son Arvaan. The same school the online site recently called the best was the school everyone was talking about.

Garima said it took two years before Arvaan’s name floated to the top of the admission lottery.

“We were happy because that's what we wanted: for him to be in one place, make good friends, have a good time,” she said.

But Arvaan didn’t even set foot in a classroom before the Bannerjees began to have misgivings.

“It was the orientation meeting for a new class,” Garima said.

Arnab said for him there was a clear message from the school administration.

“The school is so secluded, almost like a gated community,” he said. “And you're lucky to be on this side of the gate and not on the other side.”

Arvaan attended ACE for three years before the Bannerjees were convinced they were better off on the other side of the gate.

Academy for Classical Education principal Laura Perkins (second from left) attends a recent meeting of the school's board.

Charter schools are pillars of the school choice movement.

But sometimes, choice can veer into exclusivity. And there’s evidence that when that exclusivity is coupled with racially inequitable discipline, a school runs a very real risk of not serving everyone who is enrolled, of undercutting school choice for families who aren’t white.

Those are the sorts of things Curt Fuller is on the lookout for when he is called to analyze charter schools.

“Part of the promise of charter schools is you get autonomy and flexibility in exchange for accountability,” Fuller said.

For schools like ACE, autonomy means a curriculum grounded in the Western Canon the school describes as time-tested for centuries.

But Fuller, who is director of charter school operations with the nonprofit group Building Hope, said charter schools should do more.

“Charter schools should be reflective of the community that they're in,” he said.

That’s part of the accountability. It’s one of the central tenets Building Hope relies on when it advises charter schools on how to remain fiscally solvent.

The 42 schools overseen by the State Charter School Commission receive some state funding but are divorced from the local property taxes that most conventional schools rely on for funding. Plus, they can’t charge tuition. Those are prices for autonomy.

So they borrow money.

In 2017, Macon’s Urban Development Authority helped ACE secure $36 million dollars in bond lending. When ACE violated the terms of the loan by not having the prescribed amount of cash on hand, that triggered an audit performed by Building Hope and Curt Fuller.

“I'm more concerned about the school operating well than I am about the finances,” Fuller said.

That’s because, according to Fuller, when a charter school operates well, its bondholders will likely make good on their investment.

Fuller started his ACE audit the way he starts all of his audits.

“I would look at their minority enrollment and then I would open up the U.S. Census data for 5 miles around that school and compare it,” he said.

He quickly noticed something.

“There was a pretty big gap between the community and the school,” he said.

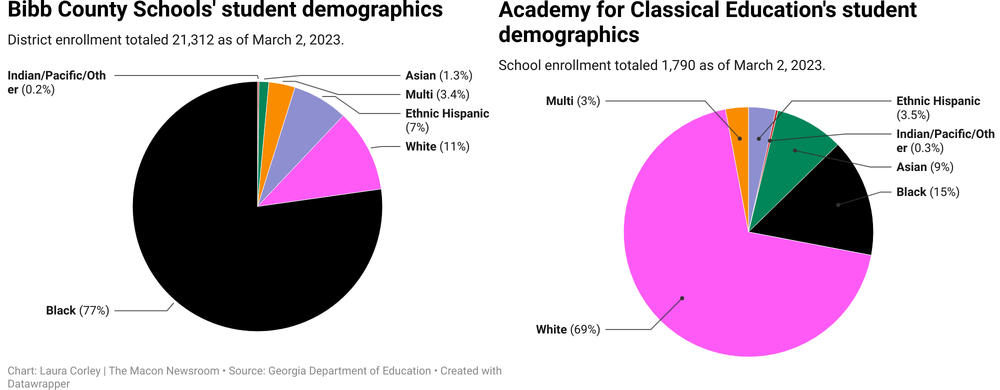

ACE is in Bibb County. And where 80% of Bibb County School District students identify as Black, the Academy for Classical Education is like the flipped image: 70% white.

A demographic comparison of Bibb County Schools and the Academy for Classical Education.

There was more. Fuller found discipline at ACE was racially inequitable, too. That’s backed up by data held by the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement. In his audit report Fuller noted “significantly higher consequences” given to non-white students for behavioral issues.

Again, according to data compiled by the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, ACE is not alone.

Most of the state charter schools with majority white enrollment are nested inside majority Black communities.

There is another similarity: White students are far less likely to be disciplined in those schools than students of color, who are sometimes disciplined two or three times more often than their enrollment numbers would suggest.

Statistically, it’s an example of something that plays out across about 20% of the schools overseen by the Georgia State Charter School Commission.

For instance, in 2022 at Pataula Academy in majority Black Calhoun County, 75% of expulsions were among Black students despite their only representing 21% of school enrollment. At another Southwest Georgia school, Baconton Community Charter School, Black students are disciplined about twice as often as they are enrolled. White students there are disciplined at a rate slightly less than their enrollment.

Curt Fuller says when those patterns surface it's a problem.

“I think it defeats the purpose of education,” he said. “If we want to give students a well-rounded perspective on life and the community that they're going to be in after they finish their education, they have to be exposed to those different viewpoints and other students.”

Fuller flagged racial inequity in enrollment and discipline as action items for ACE in his final audit.

Garima Bannerjee says her son Arvaan was in middle school when the family began receiving unsettling emails from the school.

“They sounded like something drastic had happened," she said. "And it was like 'Your son's behavior from so many months has been like this. And now it's when we're bringing it to your attention.' And I'm thinking, 'If it's been happening for this long, tell me when it happens. Let's nip it in the bud.'”

At first the Bannerjees went along with the emails and tried to discipline Arvaan at home.

“We blamed him,” Garima said.

That persisted until they just couldn’t square the emails with the child they knew.

Vashti Obryant has received alarming emails, too.

“This year I've received the most emails about Zoé and her so-called issues,” Obryant said. Her daughter Zoé Caldwell just finished seventh grade.

The email that pushed her over the edge was about how Zoé would be punished after a field trip where kids passed around a rude photo.

“And the school sent me an email that said she would not be allowed to participate in any eighth grade field trips,” Obryant said.

That meant Zoé would have no field trips to look forward to for a whole year. Obryant said out of all the kids on the bus, only her daughter was punished.

Obryant and her daughter are Black. She sees a connection between that and the way her daughter has been disciplined.

“Because Zoé's been singled out all year, almost,” she said. “Discipline with children with blond hair and blue eyes? It’s swept under the table.”

Garima Bannerjee said what she describes as a barrage of emails about her son’s behavior followed directly in the wake of her unsuccessful attempts to talk to the Principal about what Arvaan said were anti-Asian comments a teacher made to him.

“It was hard to fight because no one was listening,” she said. “Because every time you go and tell 'this is what has happened,' they wouldn't believe us.”

Eventually, Principal Laura Perkins wrote the Bannerjees,“If you feel that this is putting undue pressure on Arvaan, you are free to explore other educational opportunities for him.”

For Arvaan Bannerjee, it all amounted to a cratering of his interest in school.

“I didn't really feel like doing anything," Arvaan said. "I was just — I was not motivated."

Zoé Caldwell questioned how much anyone even wanted her at school at all.

“Like 5%," she said. "Probably not even that."

Arvaan has long since moved to a different school. Zoé will attend a new school in the fall.

Vashti Obryant (left) and her daughter Zoé Caldwell.

Francis Pearman is an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University. He said struggles to thrive in school like Arvaan and Zoés are joined at the hip to fairness gaps in discipline.

“What we found is that, in fact, those two disparities are two sides of the same coin,” he said.

In their 2019 study, Pearman and his co-researchers looked at standardized test scores across racial groups in school districts across the country as well as patterns of discipline in those districts.

They found that where discipline was more disproportionately applied, test scores for the kids labeled as troublemakers dropped. This was especially true for Black students. But they also found the opposite to be true in schools that are racially balanced in discipline.

“Those schools are also likely the same schools that are meeting academic needs of the students as well,” Pearman said.

But application of discipline is not a component of how the Georgia State Charter School Commission judges success.

In emails, representatives of the Georgia SCSC explained their main measures are a charter school’s standardized test scores compared to the average test scores of the neighboring traditional school district.

When you look at test scores, ACE does outperform the Bibb County School district. But it is not an apples-to-apples measurement.

For ACE, there weren’t enough Black students who took the high school end of course social studies test in 2022 to show up in the data.

And in a county with 30% poverty, no economically disadvantaged students were tested at ACE at the high school level.

Francis Pearman says these are the things to consider when choosing a school.

“The best prediction isn't how well that school serves the average student,” Pearman said. “The prediction is how well that school has served students who look like your students. That's the difference, right?”

And so what if parents hope their kid can endure disparate treatment in return for the chance for academic opportunity?

“That's a hell of a compromise to make as a parent,” Pearman said.

ACE Principal Laura Perkins denied requests to talk about the issues of racial equity in enrollment or discipline at her school. The last request to do that was in person, before the board meeting where she touted ACE being named the best school in Middle Georgia. She declined there, too.

“No, I’m not going to talk about it,” Perkins said before closing a door between the school lobby and a hallway.

The SCSC, which supplements ACE's budget by about $14 million annually, also declined requests to specifically discuss issues of racial equity in their schools.

Today, Garima Bannerjee says she wouldn’t advise parents experiencing what her family did in waiting three years to leave the Academy for Classical Education. And she says parents considering ACE should ask themselves a question.

“Will my child be happy, especially if I'm not a white person?" she said. "Is my child going to be happy in the school?”

Vashti Obryant takes a different tack.

“If we don't send our Black children there, if we don't send our Indian children there, if we don't send our Hispanic children there, if we don't send our Korean children, our Vietnamese children — if we don't send any of those children there, then what?” she asked, before answering the question herself.

“They win. That's it.”

Meanwhile, in its strategic plan, the Academy for Classical Education lists outside concerns about diversity as one of the external threats to the school.

ACE Principal Laura Perkins denied requests to talk about the issues of racial equity in enrollment or discipline at the school.

This story was co-reported with Laura Corley of the Macon Newsroom.