Section Branding

Header Content

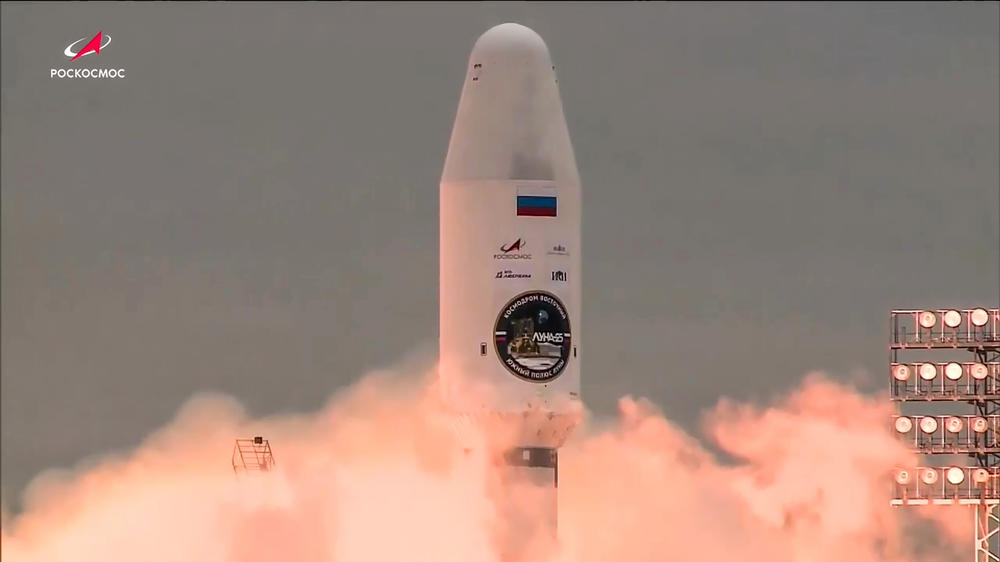

Russia and India are landing on the moon next week. Here's what you need to know

Primary Content

Russia and India are just days away from attempting to land robotic missions near the south pole of the moon.

Russia's Luna-25 mission is currently scheduled to attempt its landing on August 21, while India will try to land its Chandrayaan-3 probe on August 23.

They're also landing quite near each other on the lunar surface, according to Brett Denevi, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

"They're just a few hundred kilometers apart," she says. "They'll both be not quite at the moon's south pole, but in the general polar region."

The south pole may seem like the coolest place to land on the moon right now — China and NASA are planning to send their own missions to the area too — but it also hosts some of the coolest places, literally. That's because some craters near the south pole lie in permanent shadow.

"Those areas never see sunlight, and thus they're just extremely cold," says Denevi.

That means they could have frozen water. Denevi says the water is interesting from a scientific standpoint because it could provide clues about how this life-giving compound came to our part of the solar system. It's also a valuable resource: Any nation that gets ahold of that precious H2O would be able to use it for all sorts of things.

"If you break it apart you could make rocket fuel or breathable air for astronauts on the surface," she says.

Russia's Luna-25 mission is a return after decades

Russia is no stranger to the moon, according to Anatoly Zak, the publisher of RussianSpaceWeb.com. When it was part of the Soviet Union, it made more than a dozen trips to the moon.

"The last such mission took place in 1976," Zak says. He says this new mission is actually based off of the old Soviet design. "It's a kind of upgraded 21st century version of that Soviet spacecraft that landed on the moon in the 70s."

As a nod to that heritage it's been named Luna-25, the next in the sequence of old Soviet missions.

This mission has been in planning since the late 1990s, Zak says. It's a relatively small four-legged lander with a robotic arm it can use to collect surface samples.

Because it's a proven design, it should work pretty well. On the other hand, everyone who designed it and flew the old Luna missions nearly a half-century ago have since retired. Zak isn't really sure if they'll be able to stick the landing.

"Probably there's a 50-50 chance that they will be successful," he says.

India's Chandrayaan-3 is a retry of an earlier failed attempt

In some ways, landing on the moon is trickier than landing on a planet like Earth.

"The moon is kind of a unique challenge because it has no atmosphere," says Jason Davis, an editor with the Planetary Society, a non-profit devoted to space exploration.

The lack of atmosphere means there's no way to slow down using a parachute. Instead, spacecraft must rely on thrusters to break their fall at just the right moment.

"You have to make a lot of sophisticated calculations as you come in for landing to fire those thrusters just right," Davis says. "There's not a lot of margin for error."

The Indian Space Research Organization knows this all too well. In 2019, it tried to land on the moon as part of its Chandrayaan-2 mission. But when the engines on the lander performed in an unexpected way, "the spacecraft did not know where it was, and crashed," Davis says.

Chandrayaan-3 is basically a repeat of that failed 2019 attempt, Davis says. The lander has instruments to study seismic activity on the moon, along with other aspects of the local environment, such as radiation and temperature. It's also carrying a small solar-powered rover.

Davis thinks that India likely has learned a great deal by analyzing the data from its failed 2019 landing attempt. That means that Chandrayaan-3 is more likely to succeed, he says.

Then again, anything can happen on the moon.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.