Section Branding

Header Content

Why the UAW is fighting so hard for these 4 key demands in the auto strike

Primary Content

Updated September 20, 2023 at 10:53 AM ET

Even United Auto Workers president Shawn Fain admits the union's demands in its ongoing strike against the Big Three automakers are "audacious."

From demands for wage increases of around 40% to cost of living protections, the UAW is drawing a hard bargain in its negotiations with General Motors, Ford and Stellantis — and many autoworkers strongly believe it's what they deserve.

After launching a strike at three auto plants last week, Fain is threatening to expand the walkout unless the automakers offer substantially better deals than what's currently on the table.

The automakers are adamant the wage and benefits demands from the union would put them at a competitive disadvantage, especially as the industry navigates the transition to electric vehicles.

But from the UAW's perspective, the current demands represent a long-overdue redressal for all the concessions the union made to prop up the automakers just before and after the 2008 recession — concessions workers still feel to this day.

Here's a look at four of the UAW's key demands.

Wage increases of about 40%

Wages are, for obvious reasons, the biggest sticking point in ongoing talks for a contract.

The UAW is pushing for a roughly 40% general wage increase for its members, over the length of a four-year contract, pointing to automakers' recent profits. Collectively, the three companies posted a profit of $21 billion in just the first half of this year.

So far, the companies have offered pay raises of approximately 20% — a jump from their opening bids, but still only half of what the union sees as adequate.

The pay hike demands are being driven in part by the success other unions, including at UPS and American Airlines, have had in getting similar increases this year.

But for autoworkers, it's also personal. The contract UAW negotiated in 2007 included a freeze in base wages for workers over the length of the four-year agreement.

As a result, the average hourly wage for workers manufacturing motor vehicles and parts has dropped by more than 20% in the past two decades when adjusted for inflation, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Another dynamic driving the UAW's wage asks? Skyrocketing CEO pay.

General Motors CEO Mary Barra, the highest-paid chief executive among the Big Three, made nearly $29 million in 2022. Securities and Exchange Commission filings show that this is 362 times the median GM employee's paycheck.

"Obviously, CEOs should be the highest-paid person in an enterprise," says Economic Policy Institute Chief Economist Josh Bivens. "But the question is, how much higher than everyone else?"

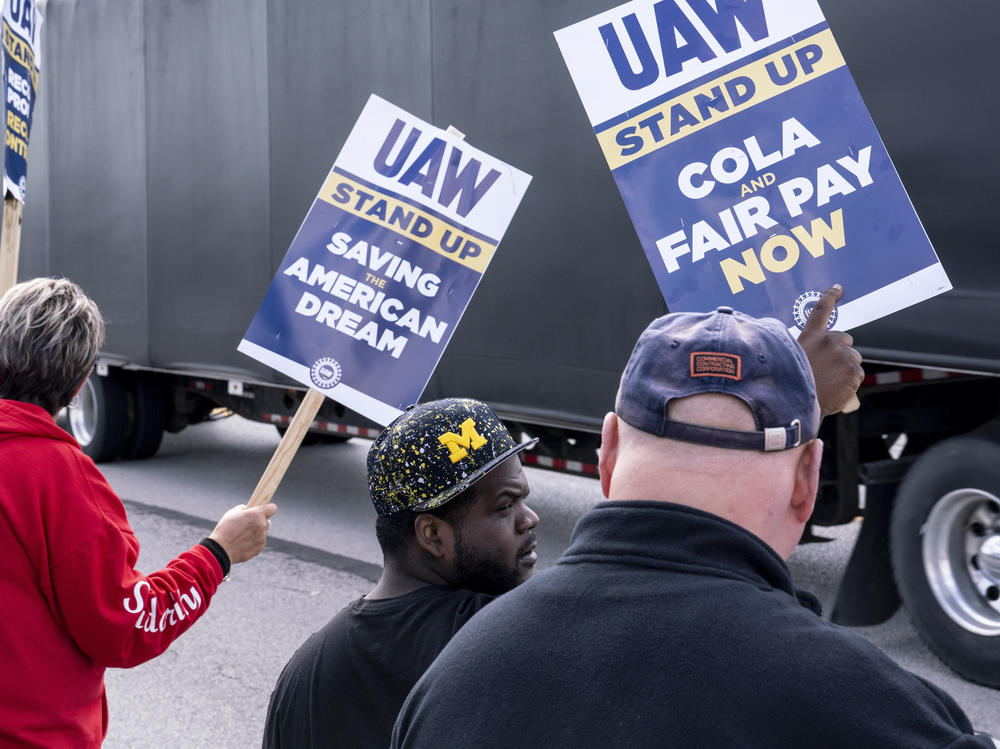

Reinstating cost of living protections

Autoworkers also gave up cost-of-living-adjustments, or COLA, as part of the concessions to automakers during the 2008 financial crisis.

The UAW is now pushing for a reinstatement of cost of living protections, to ensure wages keep up with inflation over the course of the next contract.

The old COLA formula, according to Professor Harry Katz of Cornell's School of Industrial and Labor Relations, provided workers with roughly 90% protection against inflation.

So, for example, had auto workers still had COLA in their contracts in the summer of 2022 when inflation hit 9%, they would have seen an increase close to that in their base pay based on COLA alone.

"They're asking for two things: they want payback for the loss of real income they suffered because they didn't have a COLA clause over the last several years, and then they want future protection for future inflation," Katz said.

The automakers have put COLA proposals on the table. But Fain has called the companies' offers deficient saying they don't meaningfully protect against inflation.

"That's not COLA. That's not even diet COLA. That's Coke Zero," Fain quipped earlier this month.

Ending the two-tier system for wages and benefits

A handful of the UAW's demands are intended to level the playing field for new hires — in terms of wages, health care and retiree benefits.

Since the 2007 union concessions, new workers have been paid less than veteran employees to do the same job.

In 2019, the companies agreed to an eight-year progression scheme, meaning a new hire can eventually work their way up to the same pay as their colleagues, over the course of those eight years.

Now, the UAW is pushing for a 90-day progression to the top rate, which Michigan State University professor Peter Berg said would virtually eliminate the tiered wage system.

The companies have countered with an offer for a four-year progression to the top rate.

Health care and pensions are also wrapped into the UAW's fight to eliminate tiers. Concessions right before the financial crisis placed new hires in a lower tier for health are and pensions, while existing workers kept their benefits, said Kate Bronfenbrenner of Cornell University's School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

"Companies are doing this despite research that shows two-tier is harmful for the company and workers," Bronfenbrenner says, pointing to the effects of the tiers on worker morale.

The UAW has referenced the Teamsters union's success in eliminating some tiers at UPS this year in arguing that the Big Three automakers can do the same.

Job security in the EV transition

Looming over the UAW's negotiations this year is the transition to electric vehicles — an industry-wide shift that, from the union's perspective, underscores the need for strong protections for workers, including when existing plants are shut down to shift production to EVs.

The union wants a guaranteed right to strike over plant closures and some form of compensation in the event of a shutdown of the plant.

"It's a demand that takes an adversarial approach to the future of the industry," Berg, of Michigan State University, said, referring to the use of a strike as leverage.

However, the companies argue they need to have the flexibility to shut down or move operations. They've already pointed to the high cost of EV transition to explain painful cuts, like when Stellantis — the parent company of Chrysler — shut down a plant in Belvidere, Ill., citing the high cost of the EV transition.

Bronfenbrenner, of Cornell, said employers often use the threat of a closure to weaken union bargaining demands and prevent organizing, which she said can have a "chilling effect" on union activity.

Stellantis says they have made an offer to the UAW that includes a "strong future" for Belvidere without specifying.

The company has also demanded the unilateral right to close and sell 18 facilities, including assembly plants and parts depots, according to the UAW.

That's not something the UAW is willing to accept.

"Unions want to be able to use their one weapon of strikes," Bronfenbrenner said.

Andrea Hsu and Camila Domonoske contributed reporting.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.