Caption

A young cotton boll, likely eaten by a deer, in one of Neil Lee's cotton fields (left). By the tree line, the cotton bushes in this field are surrounded by deer tracks (right).

Credit: Sofi Gratas / GPB News

|Updated: November 2, 2023 10:17 AM

Between wavering crop prices and high production costs, financially, farmers are dealing with a lot right now.

Now, many in Georgia and other farming states are raising the alarm about white-tailed deer, which can cause millions of dollars' worth of damage to the state’s most profitable crops.

“This year has been, by far, worse than I've ever seen,” said farmer Neil Lee, who lives and works in Dawson.

Lee runs a 10,000-acre row crop farm with his brothers and dad. They grow peanuts, soybeans, pecans and cotton. In one of the farm’s cotton fields planted later this season, Lee points out the damage.

“There should be a plant every 5 or 6 inches,” Lee said. “But as it comes up, they just steady bite it off.”

Patches of dirt surround young cotton bushes with snapped branches and missing cotton bolls.

“The young bolls like that are still real juicy,” said Ethan Cody, agronomist for the farm. It’s the deer’s favorite snack.

A young cotton boll, likely eaten by a deer, in one of Neil Lee's cotton fields (left). By the tree line, the cotton bushes in this field are surrounded by deer tracks (right).

Deer are prone to eat the younger plants, which can keep them from growing or kill them completely. Lee has to either replant the crop or incur losses.

“See the tracks here?” Lee points to tracks surrounding all the cotton bushes. The tracks are big and small, for bucks and does. “And then if you look, I mean, just all this should be cotton.”

South Georgia farmer Neil Lee points to spots in one of his row crop fields where deer have stunted the growth of young cotton bushes.

Some miles away, in one of Lee’s soybean fields, the plants are ankle height near the tree line — half as tall as they should be. His peanut field looks mowed down. Any plant closer to the deer’s habitat is at risk of getting eaten. Lee said he’s likely incurred damages in the six-figure range.

“We've always got deer damage but the last couple of years it's just seemed to get worse and worse,” Lee said.

Georgia’s agriculture industry is No. 1 in terms of economic impact. In 2022, cotton brought in $1.2 billion dollars to the state, peanuts brought in $716 million and soybeans earned $96 million. There are over 41,000 farming operations in Georgia.

“We think this is one of the most, like, pressing issues that farmers across the state are facing right now,” said Adam Belflower, who lobbies for the Georgia Farm Bureau. “It doesn't matter what county that I've been to in the past few months. If I go to a county meeting, I'm probably going to hear something about deer damage.

Wildlife nuisance isn’t a new problem for farmers. Feral hogs have made headlines for wreaking havoc on crops, too. But Belflower said lately, the conversation has shifted to deer, and the bureau’s been hearing about deer in more fields.

“I would say the complaints are starting to come from more commodities, has been the big thing that we've learned,” Belflower said, like in cotton. “We're seeing farmers that are losing significant yield.”

A study published by University of Georgia researchers in 2017 calculated losses for 109 farmers experiencing deer damage at $33,000 annually per farmer. Total, that amounted to $2.7 million in losses incurred from destroyed crops.

Georgia's not alone in all this. Reports from Alabama, North Carolina and South Carolina this year have shown row-crop farmers reporting increased losses from deer damage.

But while some farmers swear there are just more deer, populations in Georgia are stable, according to harvest data from hunting season. Other research shows the number of deer in North Georgia has actually gone down, due to habitat changes, and more bears and coyotes.

Charlie Killmaster is the deer biologist for the state of Georgia. While he recognizes that it’s possible deer populations have grown slightly in Southwest Georgia, Killmaster said the more money farmers can get for what they grow, the more likely they see deer damage as a problem.

“As the value of crops, the amount that they can be sold for, goes up, the number of deer control permits goes up,” Killmaster said.

Deer control permits are issued by the state and allow farmers to shoot a limited number of deer in their fields.

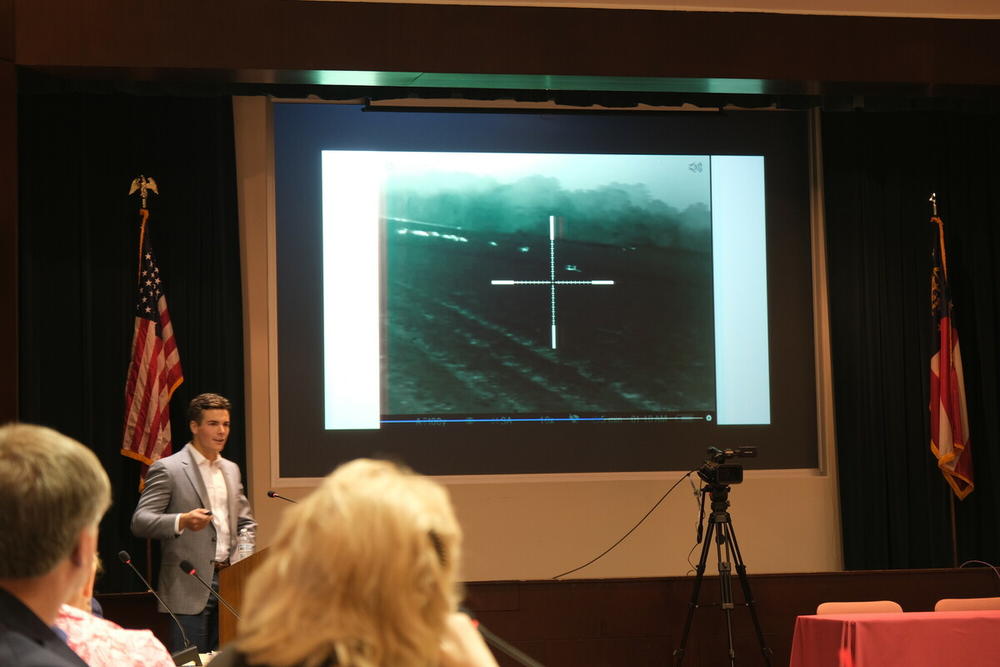

Adam Belflower shows members of Georgia's Rural Development Council a video from a South Georgia farmer where deer can be seen eating cotton through a thermal scope.

“We've looked at this in the past, and there's usually no direct correlation between deer population trends or deer population size and the number of deer depredation permits that we issue,” Killmaster said. “There is more of a correlation in the all crops price index.”

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the prices received for all crops has increased by almost 30% since 2021. The value of cotton spiked last year at just over one dollar per pound — the current value is around 80 cents per pound.

At the same time, it’s also gotten a lot more expensive to grow crops. For example, the cost of fertilizer has more than doubled since 2020, alongside other input costs like for chemicals and fuels.

That leaves many farmers less likely to pay for preventative measures against deer, like fencing.

“If you're operating on thin margins, because seed is more expensive, because fertilizer is more expensive, because diesel is more expensive, because equipment's more expensive. … Anything on top of that is going to make it harder to remain profitable,” said Belflower with the Georgia Farm Bureau.

For Neil Lee back in Dawson, these financial stressors are all too familiar.

“I've enjoyed farming, but it is getting tough right now to survive,” Lee said.

Lee has gotten permits to shoot deer on his land — and it’s helped. But those permits expire by the time deer hunting season rolls around in October.

“I feel like it's going to be this bad or worse for years to come until something is done,” Lee said. “And I don't know what the answer is. I do know that more need to be killed.”

To do that, Lee is planning to lease his land to hunters this fall, in hopes of getting some extra protection for his crops.