Section Branding

Header Content

Food from Appalachia is popular right now. But that wasn't always the case

Primary Content

LISTEN: GPB's Devon Zwald speaks with Erica Abrams Locklear about her book, "Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food & People."

Food from Appalachia has grown in popularity in recent years.

National publications have written articles about it and restaurants have opened dedicated solely to the cuisine.

But at the turn of the 20th century, the nation viewed Appalachian food as "coarse."

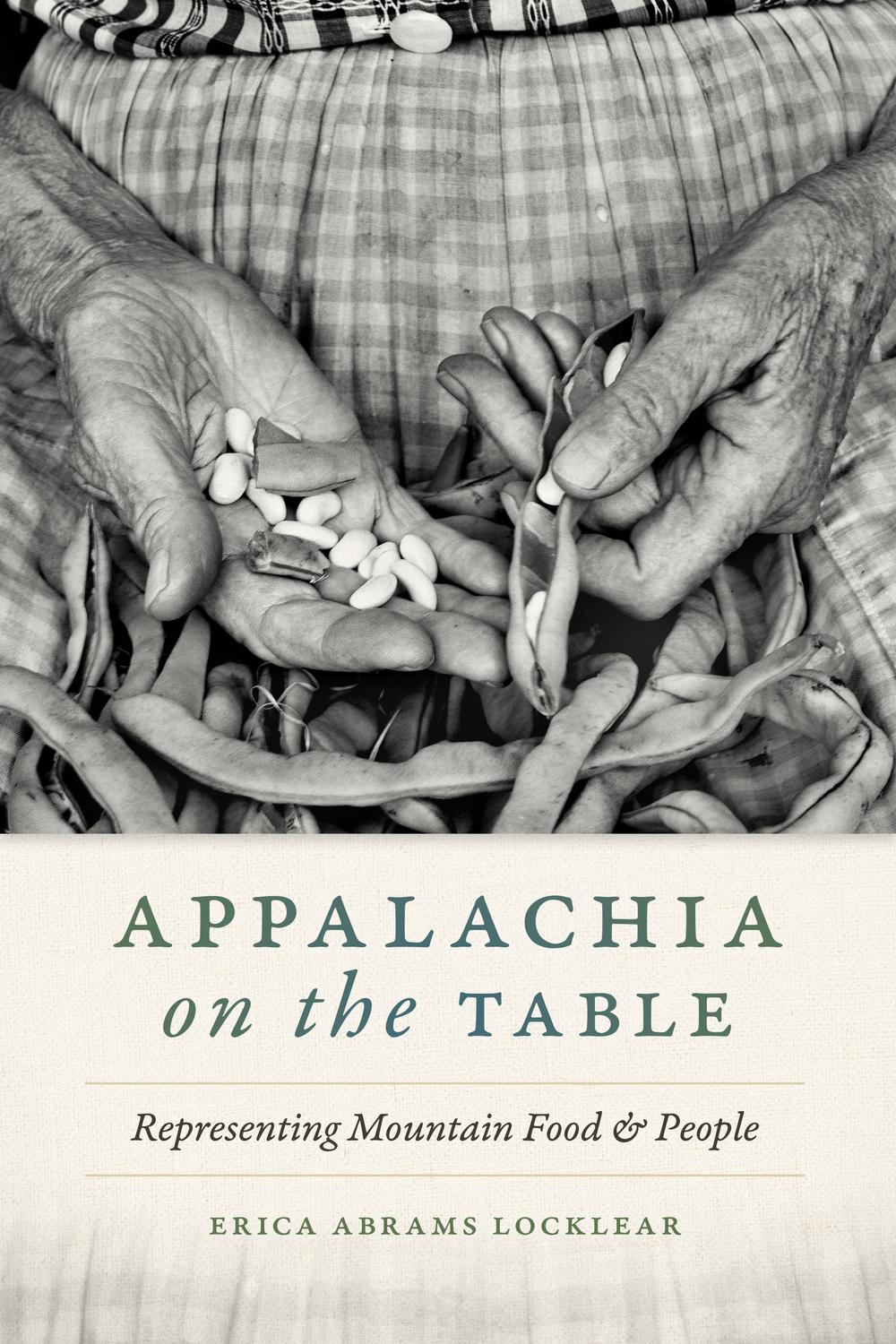

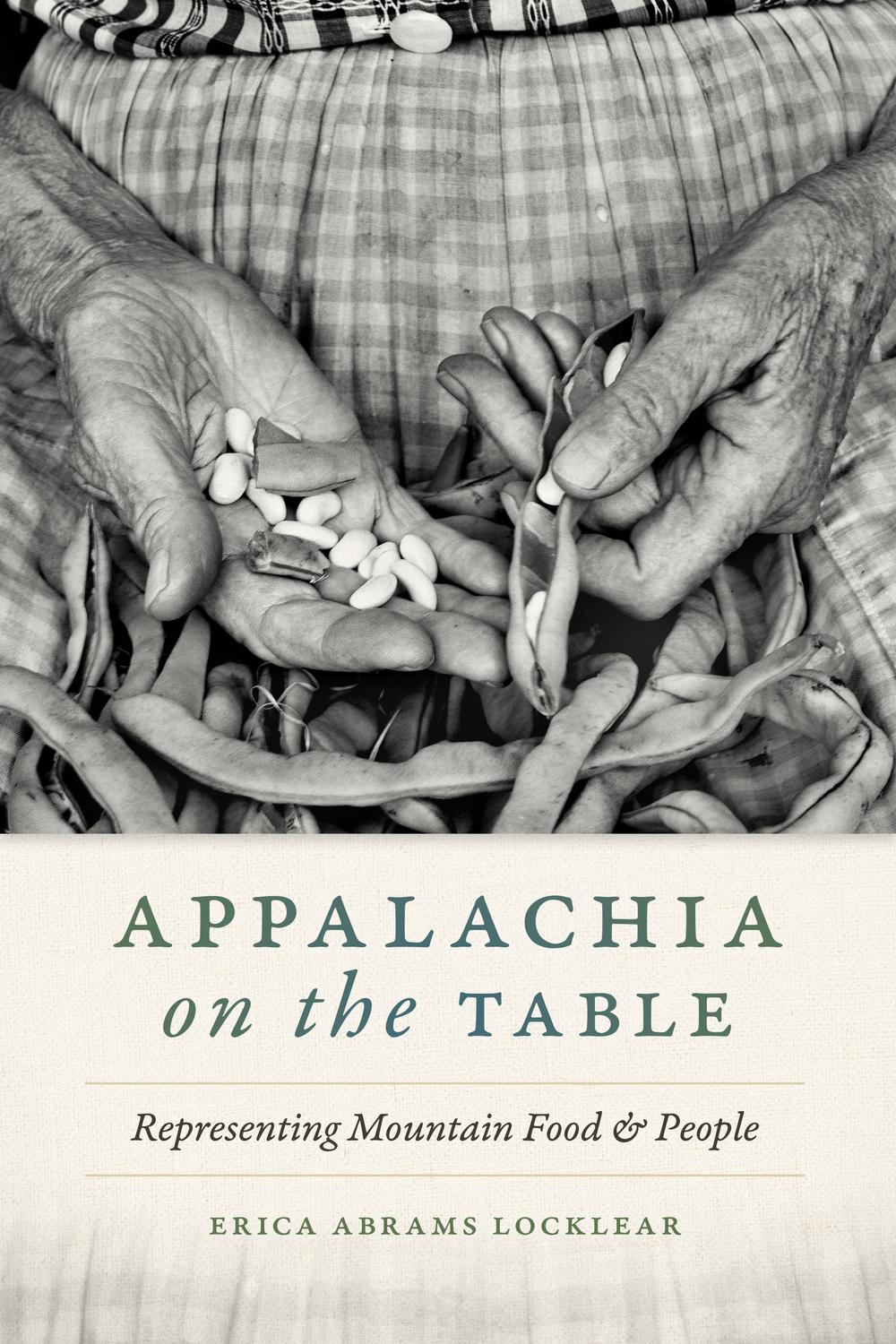

Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food & People by Erica Abrams Locklear examines how Appalachian food is represented, how those representations influenced stereotypes of Appalachia and its people, and how the nation went from viewing Appalachian food as coarse to celebrating the cuisine for which one of its staples, ramps, can now cost $20 a pound.

Devon Zwald: [There’s] a concept that emerges in the late 1800s and early 1900s that you talk about in your book that calls Appalachia a region distinctly separate from other parts of the country. How did people arrive at this viewpoint and how did food specifically contribute to that emergence?

Erica Abrams Locklear: It's an interesting question that scholars, historians, American studies folks, literature critics have been grappling with for quite some time. So local color writers, in particular, and writers of travel narratives in the late 1800s and early 1900s are often cited as sort of part of the cultural genesis of a lot of ideas about Appalachia. A scholar named Henry Shapiro is probably the best-known person to write about that. And so I was building from his ideas and what I noticed I found really fascinating and equally disturbing is that in a lot of that literature where you find some very familiar stereotypes even today of mountain people, the descriptions of food were very similar. And that one word in particular kept coming up, and that's "coarse" — c-o-a-r-s-e. And when it was used to describe the food, the idea was that it was too greasy, it was not properly prepared, it was difficult to digest and it was something to be avoided. When the word was applied to people then the idea was that these people who were consuming this coarse food were considered uncivilized or unsophisticated or uncouth and, like the food, probably best avoided. And it was a paradigm that I saw coming up again and again.

Devon Zwald: There are also a lot of examples of celebrations of Appalachian foods in the book. How did these celebrations complicate people's perceptions of the region?

Erica Abrams Locklear: Right. So one of the driving questions of this project is how is it that you've got this sort of national idea of a region and its people and its cuisine come from such a denigrated place at the turn of the 20th century to this kind of celebrated novelty? Which is where we've arrived now. People all across America are really into Appalachian food right now. In April, the same month that my book came out, of 2023, Bon Appetit magazine published a 16-page spread called "Appalachia Anew." And there are articles in The Washington Post and in The New York Times. There are restaurants devoted solely to Appalachian cuisine. And so it's definitely being celebrated.

Devon Zwald: Is there anything that you want for people who have a new interest in Appalachian food to consider when they cook or they eat it?

Erica Abrams Locklear: Oh, yes. I think the biggest one is to be aware that it's not a good idea to curate a list of foods that count as Appalachian at the exclusion of other foods. And a lot of this has to do with the erasure of the indigenous roots of Appalachian food, with the contributions that people descended from enslaved people and free people of color have made to Appalachian cuisine. Another part of it is to be aware of access and to ask yourself how much do the ramps cost at this restaurant versus how much do they cost at the community supper. And should I go to that community supper as well?

Devon Zwald: And what are ramps? For those of us who aren't familiar.

Erica Abrams Locklear: Ramps are a forageable. Sometimes people call them wild leeks. Sometimes people call them wild onions. They're technically not an onion, but they're very related. And they're extremely strong and pungent. And so, if you eat a raw ramp, the scent of it stays with you for a really long time. And in mid-20 century Appalachia, ramps were not really considered cool. It was something that people who didn't have access to other fresh greens might eat in the springtime of the year. But there were ramp festivals at that time. But it was a very localized kind of consumption, whereas now they are extremely trendy, extremely popular and very expensive, often over $20 a pound.

Devon Zwald: You mentioned groups that have been erased from conversations around Appalachian food. How do you bring those groups back into the conversation?

Erica Abrams Locklear: Yeah, again, I think just being aware and asking questions and trying to do your own research. To go back to the ramps example, ramps are an important part of Cherokee culinary history as well, and there are ramp festivals in Cherokee, North Carolina, that coincide with the opening of trout season.