Section Branding

Header Content

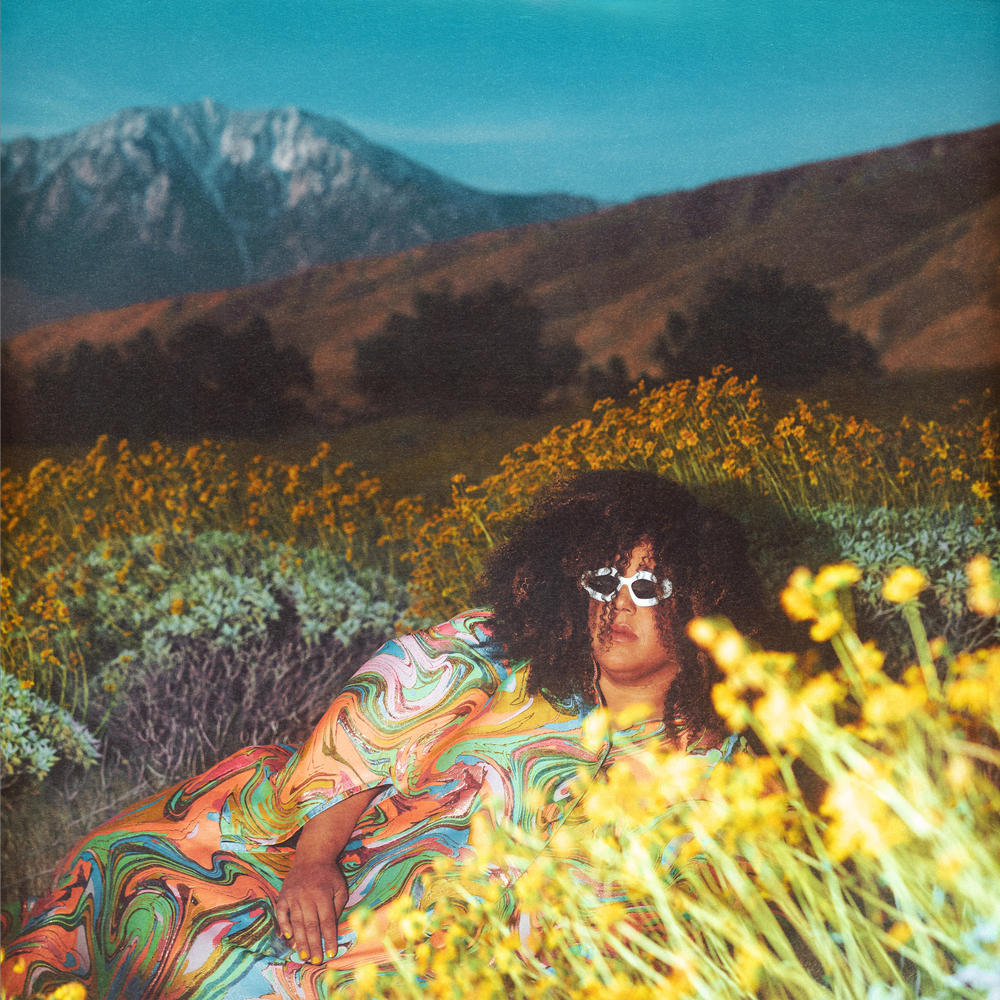

Brittany Howard is going to make her dreams come true

Primary Content

By the standards of the 2020s, when younger audiences metabolize music so quickly that performers need to keep a constant flow of memeable, streamable content coming, Brittany Howard's been laying low. Since wrapping the tour promoting her 2019 solo album Jaime and commissioning remixes of it from peers, she's resurfaced only a handful of times leading up to the announcement of her second solo album, What Now, which will be out Feb. 2, 2024. Despite the title's lack of an explicit question mark, there's one strongly implied. After sprinkling her attention across wildly varied one-offs — an Earth, Wind & Fire update for a kids' movie, an HBCU marching band-inspired anthem for a pro soccer team founded by women and a collaboration with an experimental composer — she's been asking herself what she can dream up next.

Geographically, Howard's not all that far from the resourceful, rural north Alabama environment where she grew up and formed the soul-steeped rock band Alabama Shakes in the late 2000s. Just before the pandemic, she moved into a chicly remodeled cottage 100 miles up the interstate from Athens, Ala., on the east side of Nashville, where the statement piece currently hanging in her living room is a floor-to-ceiling mural of The Supremes, salvaged from the city's first gay bar. Philosophically, she's ventured into realms wholly beyond the prejudiced constraints projected onto her as a big-voiced Black woman from a working-class Southern background in the Shakes' early days. In some readings of that period, Howard was seen as operating purely on instinct, as if she'd stumbled onto a knack for unleashing some sort of primitive energy.

The reality is that Howard's dedicated herself to unbounded exploration. In late October, she gave me a tour of her studio, a detached garage behind her home with recording gear of various vintages, including a console that, she noted, Prince used to record an alternate version of his debut album in the late '70s. At my request, she fired it up to play a demo of her forthcoming album's newly released title track. The elements that lend the completed version a muscular and exhilarating sense of friction were already present: the rhythm guitar's funky filigree; the antsy bass line tugging against the polyrhythmic drum groove; the crisp vocal cadence, with nonsense syllables as placeholders. Howard had the vision. The limitations were merely practical, and readily overcome once she convened her trusted circle of collaborators in a much larger facility, Music Row's historic RCA Studio A. "I usually blueprint the idea out and then I'll just go and get all the sounds I'm imagining," she explained, "because I can't really make them in here."

Heading toward Howard's house, we passed her bass fishing boat, its blue hull visible beneath a canvas covering. At her granite dining table, she retrieved a laptop containing more of her demos, including one for a tempestuous dream-pop number called "Red Flags" — just released as the album's second single — whose off-kilter, mightily complex beat she'd mapped out electronically. "I've heard a great drumbeat over and over again," she said. "So how do you just screw it up? That's what I do, because that's exciting to me."

On the stage of Nashville's Ryman Auditorium in early November, Howard entrusted that part to the virtuosic drummer Nate Smith, who'd also played on the album sessions, while she, wrapped in a colorful kaftan, served as a kind of conductor — not only to her band, but to an audience hearing the material for the first time. During "Red Flags," she charted her way through a relationship's cataclysmic breakdown, regathering her power and fashioning anguish into elegant, operatic crescendos. Soon after, the room filled with the silvery, resonant sound of crystal healing bowls, one of many moments when she seemed to be tuning the dynamics of her performance toward revelation.

A few weeks earlier, sitting at the dining room table of her Nashville home, Howard spent an afternoon meditating on the shape her life has taken since she grew into her solo artist identity, her return to the city just before the first COVID lockdowns, the beginnings of her experience with alternative therapy — and how she's coming up with ample answers to the question "What Now?" by embracing limitlessness.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jewly Hight: What have the last few years been like for you?

Brittany Howard: I moved back from New Mexico right before COVID began. The whole world shut down and I'm in Nashville in a rental house with two dogs and two cats, just trying to figure out what to do like everybody else. After a while I was like, "I'm a creative person. I should probably, like, start making music." At the time, I was entering into a relationship and it seemed really fine. So I had content in my songs of falling in love and being excited, and then as time went on, falling out of love and being sad. It was kind of a rollercoaster of emotions over the past few years.

I've just been quietly doing things and recollecting my energy, because I knew this next thing I wanted to make, I wanted to put so much of myself into it. I knew that it was going to take so much of me. For the past three years, I've been literally meditating — I do transcendental meditation — and just becoming whole again, because this kind of job that we do, it'll suck it out of you if you don't know how to fill your cup back up.

What changed for you in the three-plus years since Jaime?

When I make records, I do like to take my time, usually three years. That's usually the amount of time it takes for me to experience life and to learn something or grow in some way. Therefore my music can grow and evolve, because that's the only thing I'm really interested in doing. It would be very easy for me to reproduce the same thing over and over again.

When you stepped out front with your debut solo album, you began telling stories and articulating perspectives specific to your life, things that you hadn't brought to the Shakes. What was it like having more attention on your individual viewpoint for the first time?

When I put Jaime out, I said, "This is my ship. I'm going to sail it. If it sinks, then I sunk it." It was just something I had to do. I always follow the voice of creativity, and it was telling me to show people who I am, because I'm usually a pretty private person, juxtaposed next to who you see onstage, who's very ferocious and very loud and very proud. I've always had this duality in me. On this [new] record, I feel like a lot of that is reflected. But somehow, the pool is deeper than I thought it was.

This album, to me, asked a whole lot of questions. It's full of songs about relationships and about love, about the world, about being hopeful, about being jovial, even though s***'s all f***** up. And that being OK, too. Celebrating what we do have, people we have still. Also talking about things like depression, talking about things like working too hard and forgetting what it's like to feel that spontaneous joy. Songs about being patient with love, understanding my own patterns. I just knew I didn't want to be the same anymore. I wanted to ascend in who I am, in my being.

I turned 35 this year, and something happened, just snapped. I don't really care what anyone thinks about my expression, because it's so divinely mine.

With the second Shakes album, Sound & Color, you exploded people's limited perceptions of what that band could do, and with Jaime you revealed a whole other side of how you speak as an artist. What was left to try, or to prove, with your new solo album?

Not everybody knows that I engineer and I produce and I play a lot of these instruments. It's not necessarily something I need people to know, but maybe for the young women out there, [I want to show], "This is something we can do. We can dominate in this field." When I was younger, that was something I was kind of chip-on-my-shoulder [about]. Now the thing I'm most excited about is the connection when I'm telling my stories. I'm always surprised by the different walks of life that connect to it and relate to it from all over the place, different backgrounds and belief systems and colors and creeds and religions. I think that's amazing, being recognized across so many different genres and no one putting me in a box anymore. This is what I've always wanted. I would like in the future, when someone sees I'm putting on a new project, they go, "What's it going to be this time?"

At this point in your career, you've tried a lot of things and you've accomplished a lot. What does ambition look like to you now? And how does a new deal with a new label figure into that?

I needed resources. And I need people who are willing to trust me and who have the same kind of ideals as me when it comes to creating art, releasing art. [Former label] ATO has always been great to me. But I just wanted to do something totally new. And that was because I kind of feel new, in a way. The brass ring, to me, is being trusted as a creative person and absolutely diving into that: Don't be afraid of what people are going to think about this, because this is your one shot.

The first new song you released, "What Now," is a really taut, well-designed piece of music: Every interlocking instrumental part is its own hook. But it's also notable for the self-awareness that you brought to writing about heading towards a breakup — lines like "I don't want to fall for your potential." "I don't want to confuse you for fulfillment." "I wonder if I'm here just so I'm not alone." Where are you coming from in that song?

This song is me standing up for myself and not believing love is something you withstand. And I'm not in control of, and I'm not responsible for, how my truth makes you feel. It can mean whatever anybody else wants it to mean. But that's where I was coming from. It wasn't from a place of, "You hurt me, so I'm going to hurt you." It was just like, "I see what I've done here."

It seemed like no one paid much attention to the pronouns in your songwriting until "Georgia," when people heard you sing about crushing on a woman. But "What Now" is one of many songs on the new album where you're addressing someone as "girl." Was that a deliberate shift?

For me, it was just a callback to '90s R&B. It's just that that's how we used to speak. And because I'm a '90s baby, I also wanted to participate in the old tradition of '90s R&B: "Hey girl."

The range of postures that you've written from is ever-expanding. There are particular songs on this album, like "Earth Sign," "To Be Still," "Power to Undo" and "Red Flags," that feel like you're wrestling with what you want versus what you know you need, or figuring out how power dynamics are at play in a relationship, or preparing for a breakthrough, or clinging to a mantra.

I think it's because I'm older and wiser since the last project came out. I'm gentler and I'm softer. I also don't want my heart broken again. And I don't want to break my heart no more — you know, I participate in that as well. So a lot of these songs are like mantras to myself, reminding myself. Because you have to understand, I have to sing these songs over and over again for probably the next two years. Why not put material in there that's going to encourage me, encourage others? I have the power to do these things for myself and love myself in this way.

It feels like you have almost limitless tools available to you in your musical imagination, in the things that you're willing to try, in the elasticity of your singing voice. There are tracks on this album that are tightly constructed, and then there are pieces of music that are elliptical or avant-garde. How did you determine what kind of experience you want a song to be?

The direction I'm going to go in musically usually has to do with my headspace. So a song like "Samson" is [capturing], "I've thought about this so much, I'm so tired of thinking about this. I'm split in two, don't know what to do." I wanted it to feel abstract and loose, but I also wanted to have this hook that was accessible, that you could sing over and over again. And then a song like "Every Color in Blue" feels chaotic and hectic and kind of scary, but also very warm and close and familiar. "Another Day" feels bombastic, like the world's on fire, but also kind of joyous because no one's really taking it very seriously, because I don't think we can handle it. I think our heads would explode if we thought about this too much.

Leading into "Another Day" is an excerpt of Maya Angelou reading her poem "A Brave and Startling Truth." How did you want that to set the tone for the song to come?

Well, I don't want to be preachy. I just know that I heard this poem that she read to the U.N. She was talking about mankind as an equally creative force as we have been a destructive force, and we're always giving so much credence to fear and to being destructive. But there's all these wonderful miracles that we do for each other. And she's just reminding all of these leaders, who fight wars and create famines, create empires on the backs of other people, "There's power that you have. You can also do something really magical and wonderful and immense." And I was like, "Yes, I feel the same way. I think about that too, Maya Angelou." Of course, I'm not as eloquent as Maya Angelou, hearing the tonality of her voice and the seriousness of the air in the room, but I have my own feelings and emotions about it.

There aren't a lot of songwriters who will set one tone with a lyric, melody or chord progression, then give you a contrasting tone that creates a strong sense of dissonance. But you're playing with that a lot. What makes that interesting for you?

I think of showtunes. I think of, in the earlier century, how sad love songs were — not lyrically, just musically. So sad, so dreamy, so sweeping off your feet. You know, Burt Bacharach and things like that. Italian composers and Spanish composers, Brazilian composers. Everything felt one way, but the lyrics were so, so, so sweet. And somehow it felt bittersweet, because love kind of does feel like that. Even if it's really, really, really good, there's always this little tinge of, "What if this happened?"

I like lyrics to be simple, almost like poetry. I keep it very short and sweet. I'm trying to get a lot in there in very little lines. I don't want to be too flowery. I really stay between these lines that I've set for myself, which is maybe a kind of 1950s style of writing, like prose or lyrics, something so simple and repeatable, not huge words. It always has to be accessible in some way, and it needs to do that in very short order.

But you sometimes bend the words into new shapes with your phrasing or enunciation. That's another fascinating part of how you're combining directness and abstractness, simplicity and maximalism.

Well, sure, because you have to. The music is taking up so much space. Whatever I'm saying has to be simple or it's going to be a bombardment — it's going to be too much. I create my own balance. I create my own parameters. And one of those is you can't have everything going hard all at once unless you're trying to overwhelm someone.

How protective do you feel of your creativity and your process at this point in time?

I'm like a little raccoon. I like to do things very secretly and privately. It really has more to do with, I'm so in my energy and I'm so sharing that energy with being creative and focusing that usually I don't have space — literally not even enough space to communicate with people around me. So I have to just kind of hold off and figure out what I'm trying to say this time, and then I'll bring it to the studio. Then that sort of becomes a bit more collaborative, and you'll see what surprises come in. I usually don't let anyone listen to my work until it's pretty much done, against my management's advice.

You mentioned that you do transcendental meditation. How do you seek out those kinds of experiences, and what do you get out of them?

So about five, six years ago, I was here in Nashville and I [discovered] a place called Nashville Center for Alternative Therapies. I started to go there for therapy, and then it turned into acupuncture, and then it turned into healing massage, and then it turned into sound bowls and crystal healing drums and gongs. I became curious about what are the ways I can heal myself from my life before music: being a child, losing my sister, parents divorcing, just all the crazy s*** I went through as a young one. And then also living as someone who's right there at the poverty line, and suddenly I'm 22 years old and I bought a house, and [searching for] the responsibility and the wisdom I needed to not lose it all and do something foolish with it.

I'm also an overthinker. I'm also a busybody. So I was always working, working, working, working. And I didn't realize the reason I was doing it. I had this fear within me that I would lose everything, because I was somehow, within me, still stuck in the times when I couldn't even buy groceries or I didn't have lights on or I didn't have hot water, and I was stealing electricity from the barbecue place. I was always thinking, "I don't want to go back there. I'll do anything." And that ran me down physically, mentally and spiritually, emotionally.

And so the transcendental meditation for me — first off, you don't have to believe it for it to work, so I love that. And also, it's hard to mess it up. You just show up for yourself 20 minutes twice a day and it creates this space. I became kinder. I became more focused. I'm nicer to everybody, and nicer to myself. I'm all fixed up and life is perfect now. [laughs]

I can really feel the impact of that therapeutic work on your new music, not least because you use singing bowls as segues between songs. What was the experience of bringing that part of your life into your creative process like for you?

When I think about the environment I was creating for this album, I wanted it to be embodied, because for so long I wasn't in my body. I was just a thinker and a doer. But I wasn't in there feeling viscerally. And I did notice that when I was doing those sound baths, it was always a safe space, and it was just such a nice, harmonious frequency. And so I said, "Well, I want to do that on my record, because each one of these songs isn't very consistent with each other. They're all kind of a different emotion, a different story." So these sound bowls can be the ground, they can connect everything, they can cleanse your palate, they can bring you back down to earth so I can take you somewhere else again.

What music scenes or communities do you feel a part of at this point?

Any and all and none all at once. I kind of keep to myself. I live a little bit under a rock. I'm a peaceful person. I have my dearest, dearest friends. I have my love. I have my parents and my animals. I'm actually kind of a simple person. It's not glamorous over here. I keep my house clean. I don't need Gucci this, Gucci that. I don't need the spectacle. That's just how I am.

I feel like my community right now here in Nashville consists of the queer community. We call it the Queer Mafia, and we're out there and we're supporting each other and protecting each other, because we do live in Tennessee. And there are a lot of people in the government who ... I don't know what they want. They definitely want to hold us down and not allow us to vote. I mean, I could get into politics, but I'm not going to. What I'll basically say is they're trying to take away rights from people I love very, very much, who are beautiful, beautiful people. And we're not having it. So I definitely consider myself part of that queer coalition who's just fighting for the rights of people who just want to live and have a happy life.

It's a significant thing that you want to continue to make your home here, find community here.

Yeah, absolutely. I'm also Southern through and through. "Southern" doesn't have to mean scary dudes driving coal-rolling trucks, shooting guns at stop signs, Confederate flags, racism, code switching, Ku Klux Klan. These are images people have, and they're true. These things happen here. [But] my family has been here for generations and generations and generations.This also belongs to me. And that's why I don't go anywhere, because this is my home as well as these other people who perhaps aren't as compassionate or open-minded. I can't go anywhere, because this is the place that I love and it's the place I understand and the place that understands me. I'm of it, and it's of me. And I don't plan on leaving this place. I plan on raising children in this place and settling in this place and growing food from this place. Yeah, not going to get rid of me.

Earlier in your time in the spotlight with the Shakes, you would talk about all the new experiences you were having, venturing beyond small-town Alabama for the first time. At this point, you've seen and done and gathered insight from all sorts of things. What difference does that make to your personal and artistic decisions?

There's a great existential question that I've been thinking about as of late. I grew up on a farm in a junkyard way off the road in the country in a single-wide trailer. And there's part of me that just wants the farm. I want the woods. The house doesn't have to be that nice, even. I just want peace, after such an interesting journey of life. I think ultimately, that's where I'd like to end up, just growing food and being barefoot and being with nature, being with animals, being with people I love, feeding them and nourishing them.

I never want this to turn into my job. So I feel like there's going to be other avenues that I've ventured down as well, just so that doesn't happen. I always want to keep this thing precious. Because to me, it's a very divine thing that I get to do it in the first place. So I'm going to protect that thing. And I'm going to be good to myself, and I'm going to be happy. That's what I'm aiming for. Because you get into this business and it starts off as, "I'm making music with my friends." And then it turns into tour budgets and algorithms and such things that I don't really know about, and it starts to lose its shine a little bit. So you have to be careful so that you don't turn into making s****y music, 'cause you don't care anymore, 'cause you're tired. So all I'm trying to say is, I'm going to keep making music. And I'm going to keep loving it.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.