Section Branding

Header Content

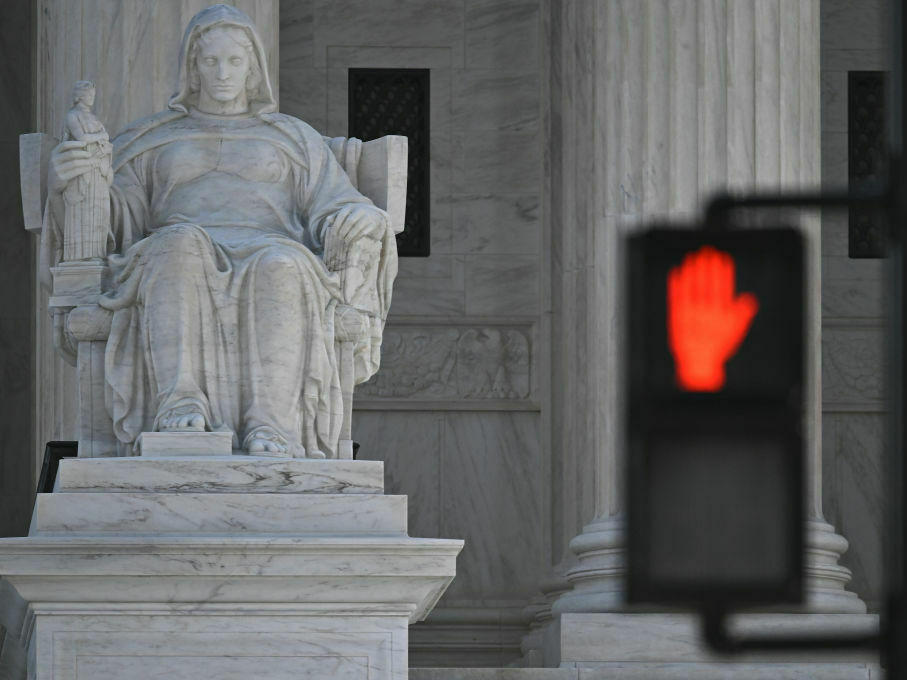

Supreme Court hears challenge to Trump-era ban on bump stocks for guns

Primary Content

Yet another gun case at the Supreme Court Wednesday. This time the Second Amendment right to bear arms is nowhere in sight. Rather, the question is the legality of a federal regulation banning devices that modify semiautomatic weapons to speed the firing mechanism.

The regulation wasn't created by the Biden administration. It was created by President Trump in 2018 after a single gunman in Las Vegas, using multiple guns modified by so-called bump stock devices, killed 60 people and wounded 400 more — all in the space of 11 minutes.

"I'll never forget the sound of the machine gun firing into the crowd that night," says Marisa Marano, who was there.

Actually, it wasn't a machine gun. The shooter was armed with 14 semiautomatic weapons, modified with bump stocks to generate rapid fire. And the carnage was so horrific that Trump almost immediately ordered the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to ban the sale and possession of these devices that the ATF now says convert otherwise legal semiautomatic guns into illegal machine guns.

The arguments in the case

Machine guns were developed at the end of the 1800s for use as military weapons in battle. But in the late 1920s and early 1930s gangsters began using them for their criminal activities, often terrorizing the streets. Congress responded by enacting the National Firearms Act in 1934 banning machine guns.

Those challenging the Trump rule on bump stocks point out that the ATF hasn't always equated bump stocks with machine guns. They argue that the agency has wrongly reinterpreted the statute banning machine guns to include bump stocks, and they maintain that the agency doesn't have the authority to do that under existing law.

At the heart of the dispute is a highly technical question about how bump stocks work in practice. In its brief for the ATF, the government notes that under the National Firearms Act Congress banned machine guns because they eliminate the manual movements that a shooter would otherwise have to make in order to fire continuously. And while a machine gun can fire hundreds of rounds per minute with just one pull of the trigger, semiautomatic weapons can't do that — at least not without modifications, like the bump stock.

Mark Chenoweth, president of the New Civil Liberties Alliance, the conservative group that is challenging the bump stock regulation, contends that bump stocks do not change the character of a weapon.

"Whether or not there is a bump stock attached to that semiautomatic weapon, a bump stock does not change the way that trigger operates," he says. "The trigger has to be pulled for each time the trigger moves ... the trigger resets between each shot."

Not so, says the government. A standard semiautomatic rifle fires only one shot each time the shooter pulls the trigger but a bump stock converts the gun into a weapon that would allow a shooter "with a single pull of the trigger, to fire at rates of up to 800 bullets per minute." According to the government, the bump stocks at issue in this case, for instance, maintain a continuous firing cycle as long as the shooter "keeps his trigger finger stationary on the finger rest."

Each side focuses on its strengths. The government stresses the lethality of semiautomatic weapons when they are modified by bump stocks. And it notes that when Congress amended the National Firearms Act in 1968 and 1986, it added that machine gun parts themselves count as machine guns.

The challengers focus on earlier ATF regulations that did not ban bump stocks under the same law, and they see the bump stock ban as another example of an administrative agency enacting a new regulation that criminalizes conduct without explicit congressional authorization.

It's an argument that plays to the Supreme Court's conservative supermajority and its increasing inclination to roll back agency powers. A decision in the case is expected by summer.