Section Branding

Header Content

Milky Way black hole has 'strong, twisted' magnetic field in mesmerizing new image

Primary Content

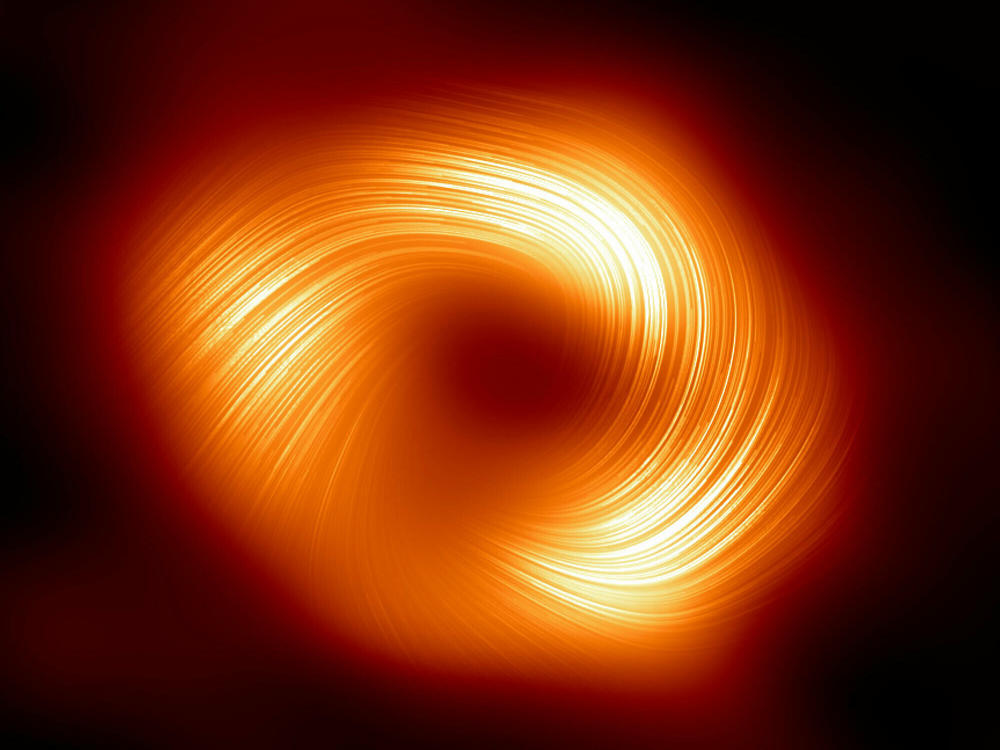

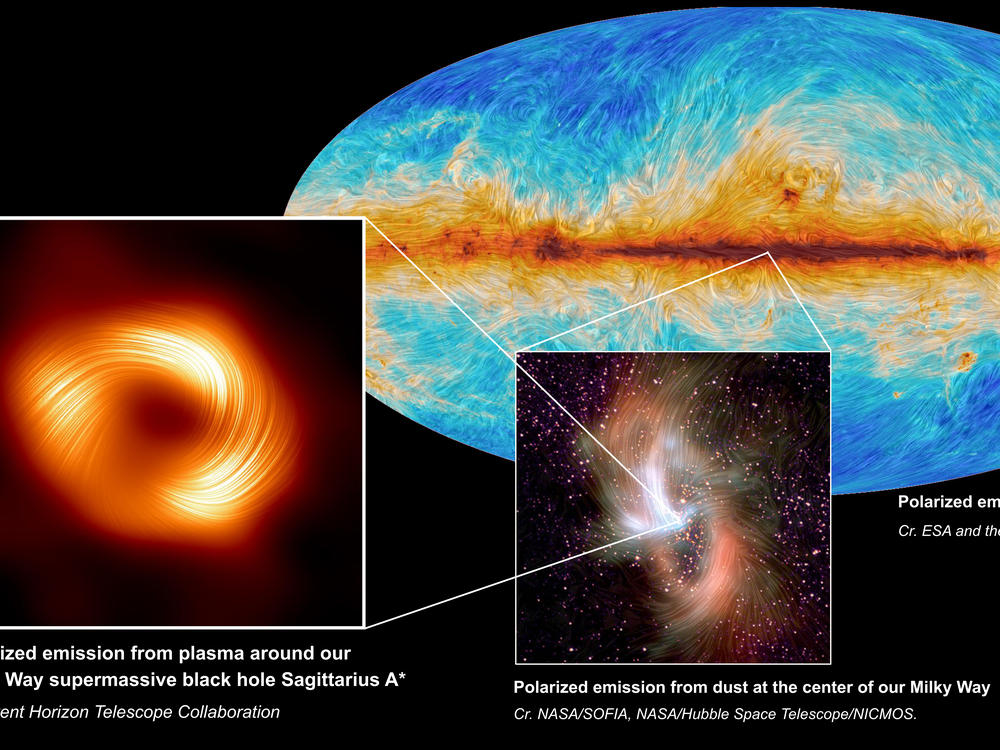

The black hole at the center of our galaxy has been compared to a doughnut — and as it turns out, this doughnut has swirls. Scientists shared a mesmerizing new image on Wednesday, showing Sagittarius A* in unprecedented detail. The polarized light image shows the black hole's magnetic field structure as a striking spiral.

"What we're seeing now is that there are strong, twisted, and organized magnetic fields near the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy," Sara Issaoun, a project co-leader and NASA Hubble Fellowship Program Einstein Fellow at the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard & Smithsonian, said in a statement about the image.

The image captures what the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration calls a "new view of the monster lurking at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy."

The doughnut analogy also applies to distance: Because of the Milky Way's distance from Earth, looking at it from our planet is similar to seeing a doughnut on the surface of the Moon.

Sagittarius A*, also often referred to as Sgr A*, is about 27,000 light years from Earth. The first image of the supermassive black hole was released two years ago, showing glowing gas around a dark center — and lacking the detail of the new image.

Black holes are famous for being "effectively invisible," as NASA says. But they dramatically affect their surrounding space, most obviously by creating an accretion disk — the swirl of gas and material that orbits a dark central region.

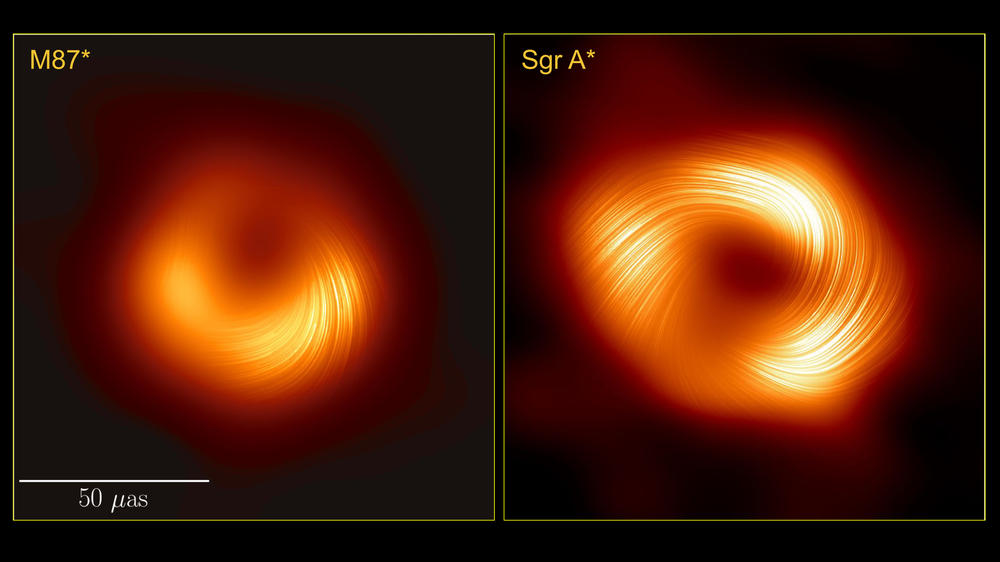

The first image of a black hole was released in 2019, when the Event Horizon Telescope project shared an image of the black hole at the center of galaxy Messier 87 (M87), some 55 million light years from Earth in the Virgo galaxy cluster. Although it's farther away, the black hole known as M87* is much larger than Sagittarius A*.

When researchers recently compared views of the two black holes in polarized light, they were struck by their shared characteristics — most dramatically, those swirls.

"Along with Sgr A* having a strikingly similar polarization structure to that seen in the much larger and more powerful M87* black hole," Issaoun said, "we've learned that strong and ordered magnetic fields are critical to how black holes interact with the gas and matter around them."

On a practical level, the black holes do have one stark difference: While M87* has a knack for holding steady, our Sgr A* "is changing so fast that it doesn't sit still for pictures," the researchers said in their announcement.

At the time the Sgr A* observations were captured, the EHT collaboration was using eight telescopes around the world, linking them together to create a planet-sized, albeit virtual, instrument. The results of their work were published Wednesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The collaboration is slated to observe Sgr A* again in April.