Caption

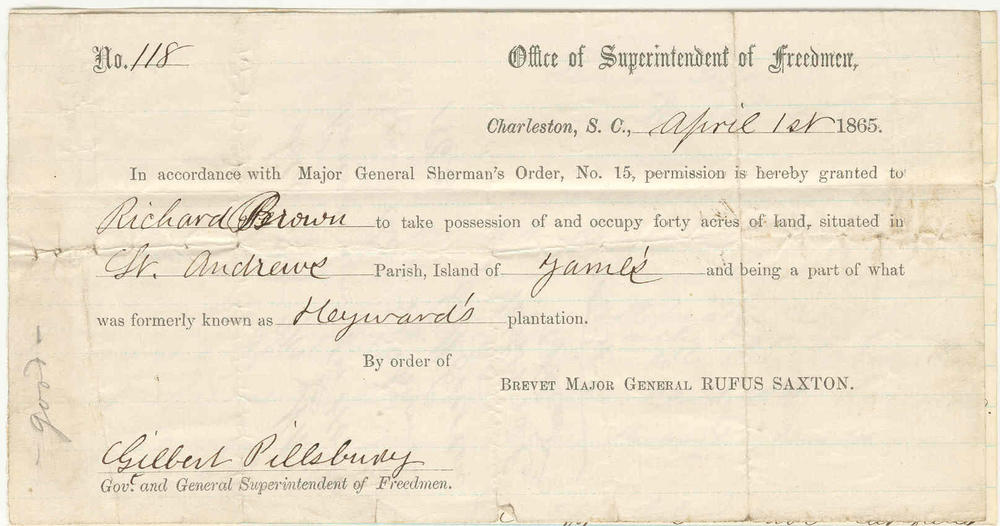

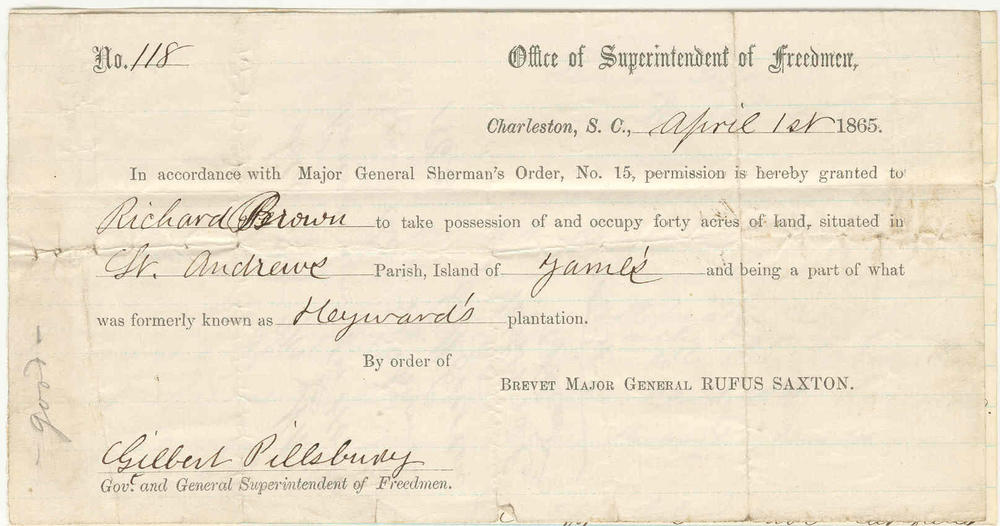

Shown is an example of the U.S. government's Special Order No. 15, which in 1865 granted formerly enslaved Black Americans 40 acres of land after emancipation.

Credit: National Archives

LISTEN: This month, Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting is releasing a story called "40 Acres and a Lie," co-reported with the Center for Public Integrity and Mother Jones magazine, which identified 1,250 Black individuals who received land after the Civil War and traced their living descendants. GPB's Pamela Kirkland talks to one of those reporters and one of those descendants.

Shown is an example of the U.S. government's Special Order No. 15, which in 1865 granted formerly enslaved Black Americans 40 acres of land after emancipation.

The promise of "40 acres and a mule" is probably the most famous attempt at reparations for slavery in the U.S., but it is mostly remembered as a broken promise.

In 1865, Gen. Sherman's Order No. 15 granted land to many freedmen and women, who built homes and communities. But after President Lincoln's assassination, President Andrew Johnson stripped this land from Black residents.

A team from Reveal and the Center for Investigative Reporting, Mother Jones magazine, and the Center for Public Integrity identified 1,250 Black individuals who received land after the Civil War and traced their living descendants. They detail what they found in the series 40 Acres and a Lie.

GPB's Pamela Kirkland sat down with Alexia Fernandez, one of the reporters on the story, to discuss how land on Skidaway Island was given to Black families and taken away. She also spoke with Mila Rios, a descendant whose great-great-grandfather was awarded land near Savannah, only to later have it taken away.

Pamela Kirkland: This month, Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting is releasing a story called "40 Acres and a Lie," co-reported with the Center for Public Integrity and Mother Jones magazine. It takes a look at the history of the 40 Acres and a mule government program, including how it impacted areas right here in Georgia. Joining me now to talk about some of the episodes are Alexia Fernandez, a reporter for the center for Public Integrity, and Mila Rios. The story of Mila's great-great-grandfather is included in the reporting about the land he was given, and that was later taken away. Alexia and Mila, thank you so much for joining me.

Alexia Fernandez: We're glad to be here.

Mila Rios: You're very welcome.

Pamela Kirkland: Alexia, one episode focuses on the land given and then taken back from enslaved people on Skidaway Island. I wanted to start with you just talking about the reporting that went into the series, because I understand this was a yearslong investigative endeavor.

Alexia Fernandez: Yes. Basically, two years ago, I found — I was I was researching a different project, and I ended up finding the titles in the National Archives, which had been recently digitized, and there was land titles that, you know, with people's names and locations. And it said Sherman's Special Field Orders 15, which I later realized was the 40 acres program. So I knew that that wasn't kind of like the narrative I knew about 40 acres and a mule. You know, it's always this understanding that it was a promise, but not something that actually happened. So, you know, we began digging into it. And it wasn't just Skidaway Island in Georgia. It was, like, land was given all, you know, through the Sea Islands. And Mila's great great grandfather got land inland, in, like, the — now, I guess now it's suburban Savannah, but it was along the Ogeechee River. So, yeah. So that's kind of how it got started.

Pamela Kirkland: And so again, looking at Skidaway, but it's now a gated, majority white community with beach houses. What led you to investigate that, and just tell me about the evolution of some of these areas that you've come across, because they're much different than what you were talking about in what was pre-Civil War time.

Alexia Fernandez: Most of them are. The ones that I had — places I went to were almost unrecognizable. That you would have to be, like, "What? This was really that plantation?" Because these plantations were massive. They were either cotton plantations on the Sea Islands or rice plantations on the mainland, on the coast. So, for example, Skidaway Island: You know, a few, maybe at the most a dozen people owned land and they were like just massive cotton plantations. And then if you go there now, you would never know. It's like half of the island is now a massive gated community called The Landings. And it's mostly white, I think maybe like 1% Black. It's really expensive. We tried to figure out how much 40 acres was now worth in that gated community, and it's about $2 million just for the land. And yeah, so we went in there and we actually spoke with people who lived there and told them about, "Hey, people got land titles on the, you know, basically where you live; on plantations that your house is located. So that was a place that we focused on just because we felt like it really exemplified what was lost from, you know — that generational wealth that wasn't passed on when this government — when this program was revoked.

Pamela Kirkland: Mila, your ancestor, Pompey Jackson, lived near what is now Savannah. Tell me what you knew about them. And what was your reaction when you found out your great-great-grandfather had received land under Gen. Sherman's 40 acres and a mule promise?

Mila Rios: Well, to be very honest with you, all of my life, I had been hearing about my great-great-grandfather because my great-grandmother lived with us, and she wanted me to always remember our family history. And she would talk to me about her father, her siblings, what life was like, what growing up was like in Jim Crow Savannah. And, so it was — it was very it was always fascinating to me. And so after her death — many years after her death — I started studying the genealogical information. So I was up on Ancestry. And to be very honest with you, I don't even think that she knew that her father had received 40 acres, because at that particular time, Pompey was only about 18 or 19 years old. He was very young, and so he did not get 40 acres. He was given four acres because he wasn't married at the time. He had no children. And I found that information on Ancestry, and I was pleasantly surprised to see that, because that was a piece of information that I was not aware of.

Pamela Kirkland: And I saw in the article, you also said that one of his biggest regrets was not learning to read and write, and so that was something he really wanted, you know, his children and I'm assuming his, his family afterwards to invest in. Do you think that that would have made a difference back then for him being 18? But with all of this going on, just having a better understanding of the land, what it would mean and what it could potentially mean for, you know, generations of family.

Mila Rios: I know he wanted an education, and I was very pleasantly surprised to see that when he went to the Freedmen's Bureau to sign some documents and to get stipends from the Union Army during the course just after the Civil War, that he had learned to sign his name: Where many people were still using X's, he had learned to sign his name. And he instilled in his children how important education was and that was something that my great-grandmother talked about all — ad nauseum, believe me. And fortunately, I'm very happy to say I think Pompey would be proud. We have all been college-educated.

Pamela Kirkland: Alexia, talk to me about some of the contrast you saw in the reporting. You have the stories of the people who were formerly enslaved, how they struggled, how they were often very poor. And then you contrast that with some of these communities and what they look like now: very wealthy, well-to-do, white enclaves. Did any of that strike you?

Alexia Fernandez: So to me, the biggest contrast was just seeing, wow, like 150 years later, it's like that — that history, it never happened. It just like by being there, you would never know. There was no marker. There was nothing. To me, that was the biggest shock. Like ... we actually tried to find as many descendants as we could of the 1,200-plus people that we found, but we were only able to find like 40 living — 41 living descendants.

Pamela Kirkland: And Mila, the series also takes a look at reparations and what might be owed to the descendants of these formerly enslaved people. How do you think your family's history may have been different, if they had retained the land that was promised to your great-great-grandfather?

Mila Rios: I'm quite sure it would have been a lot different for them. But my family didn't leave Savannah, Ga., because of lack of land. They left Savannah, Ga., because of Jim Crow. So I don't know whether my part of the family would have stayed down there or not. Because even if we had the land, Jim Crow would have still existed. So that is why we left.

Alexia Fernandez: A lot of people I spoke to had a similar view. It was like, it wouldn't have solved everything, you know, because of what was going on at the time. Like, it could have been just taken away later on.

Pamela Kirkland: Thanks to you both. You can find more information about the series at Motherjones.com/40 acres, and you can hear Alexia in Mila's episode this weekend on Reveal right here on GPB.