Section Branding

Header Content

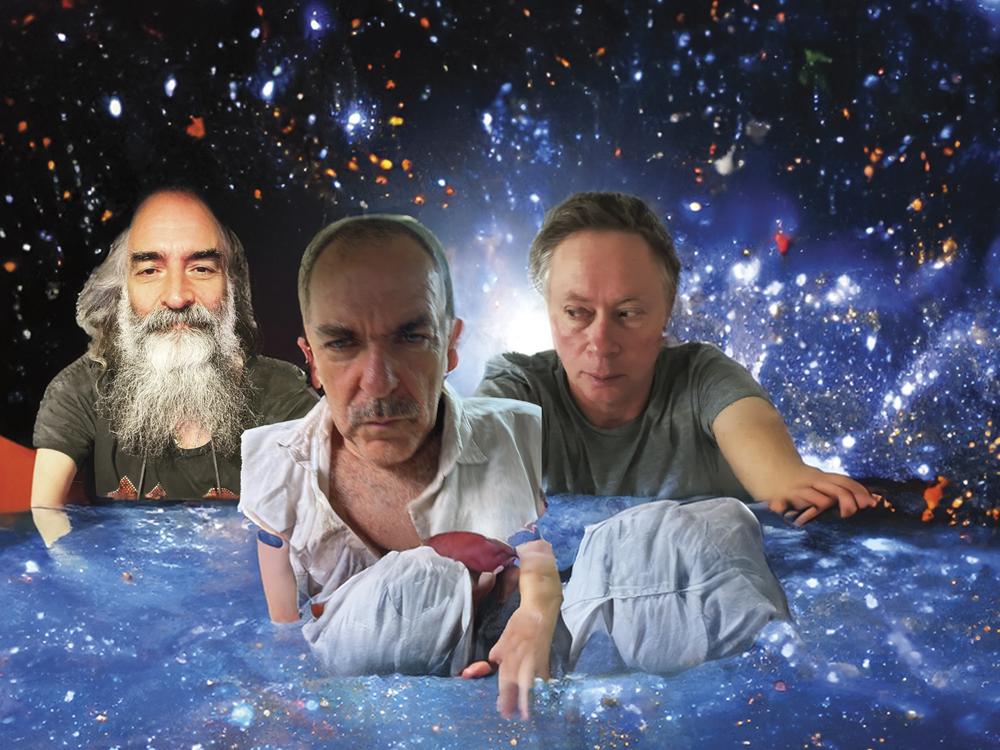

Dirty Three, instrumental rock explorers, climbs mountains with wheelbarrows

Primary Content

Warren Ellis is basking in the memory of a time, in the mid-1990s, when Dirty Three — the dirge-y and/or deafening instrumental combo the violinist had formed with guitarist Mick Turner and drummer Jim White in Melbourne — became an unlikely staple within the international rock underground.

“It was fabulous. We got to play this music in front of an audience that we probably had more hope of turning on to our stuff than any other scene,” Ellis says of the period when the band gigged both at home and abroad with everyone from Pavement and Blonde Redhead to Beck and the Beastie Boys.

“The thing that drove us was that we were always in the pursuit of… just that creative freedom,” the resplendently gray-bearded violinist adds. “Is that fair to say, Jim?”

“Yeah, I think that’s great,” comes the typically pared-down response from the band’s stubble-faced drummer, Jim White, looking on from an adjacent Zoom window and taking occasional bites off a handheld cucumber.

Now dispersed around the world — Ellis in Paris and White in Brooklyn, with guitarist Mick Turner the only one of the Three still residing in the band’s hometown — the members were all back in Melbourne rehearsing for their first Australian tour in more than a decade. The occasion was the impending release of Love Changes Everything, out June 28, their first new album since 2012 and their second for revered Chicago indie label Drag City.

Across the past three decades, each of the Three has become a celebrated presence outside the group: Ellis with a slew of Nick Cave projects, including the Bad Seeds, a duo album and numerous soundtrack collaborations; White with a murderers row of contemporary songwriting greats including Cat Power, Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Bill Callahan, the prolific lute-drums duo Xylouris White, and as of this year, his own subtly enthralling solo project; and Turner as a prolific solo artist, generous collaborator and accomplished painter, whose earthy, evocative images have adorned most Dirty Three releases, including the latest.

Amid their many individual pursuits, they’ve sporadically made time to tend the Dirty Three flame — which, despite increasingly lengthy breaks, somehow seems to burn brighter each time. Taking the form of a six-part suite, Love Changes Everything finds their core aesthetic expanding in challenging and often breathtaking ways.

Ellis still sounds fired up by the chemistry they discovered during their early meetings. He cites the “sheer thrill” of “taking everything to as loud as you can and dropping it down to nothing, and nobody knows what’s going to happen next. It was kind of — explorers. We were climbing Mt. Everest.”

“With a wheelbarrow,” White chimes in, smiling slyly.

“Huh?” Ellis asks, not catching the remark.

“Climbing Mt. Everest with a wheelbarrow,” the drummer offers. This time, the metaphor lands, and he, Ellis and Turner all crack up in unison.

'You had to take risks with Dirty Three, always'

It would be hard to think of a more apt image to illustrate the quest the trio have been on since the spring of 1992, when the three friends and collaborators from the Melbourne scene met up in Ellis’ kitchen, put together a provisional set and performed the same night at the Bakers Arms, a hotel in the city’s Abbotsford neighborhood. They gigged there regularly, finding their sound without the benefit of a stage, a PA or even a bass drum. Friends suggested they get a singer, but they saw no need.

“We just kind of felt like what we were doing was expressive enough,” Ellis says.

“There was a trust from the start: You had to take risks with Dirty Three, always,” he continues. “Just jump in and it either worked or fell flat on its face. And the three of us liked having this place that we could come and just take risks and be creative.”

“And get some free drinks,” the bespectacled, soft-spoken Turner adds with a smile.

They put out their debut LP, Sad & Dangerous, in 1994 and worked their way up to high-profile local opening slots in Melbourne and across Australia. The following year, they made the jump to America, issuing their second, self-titled LP through an earlier Chicago indie staple, Touch and Go, playing both support and headlining gigs and even doing a stint on Lollapalooza’s second stage.

As heard on Dirty Three, their sound often felt almost primordial, with Turner’s forlorn chord progressions, Ellis’ rustic fiddle (sometimes replaced by accordion or piano) and White’s sparse, wind-rustling-through-leaves percussion — making brilliant use of woodblock and tambourine in addition to the conventional drum kit — transporting the listener back to some shadowy, firelit gathering, before music was contained by anything so mundane as a rock club. Other times, they stomped like a backwoods Led Zeppelin.

Pavement’s Bob Nastanovich recalls meeting the Three through Stephen Pavlovic, who handled Australian releases for various American indie acts on his label Fellaheen Records. The trio opened for Pavement in Melbourne in 1994 and subsequently supported them in clubs across the U.S.

“We enjoyed getting blown off the stage, but after seeing these guys, then subsequently playing dozens of shows with them, it became obvious that it was going to be a repetitive situation,” Nastanovich tells NPR Music, adding, “I can honestly tell you that walking onstage after the Dirty Three is like walking on hot coals.”

David Viecelli, a.k.a. Boche Billions, Dirty Three’s U.S. booking agent since their first visits in the ‘90s, remembers being instantly impressed by the band. “It was just so distinctive, so creative, and it just had its own world, some of which was bewildering and disorienting and some of which was incredibly charming,” he says. Viecelli watched the trio build an American audience in real time, on the strength of both their music and Ellis’ rambling, fantastical and darkly hilarious between-song storytelling.

“They did get traction fairly quickly, and I think a big part of that was people seeing them live,” he adds. “You wouldn’t have seen anybody like it.”

The band’s early U.S. tours, beautifully chronicled in a 2007 documentary by Darcy Maine, were ramshackle affairs that privileged adventure over comfort, or even basic practicality.

“Mick bought a car. It was a gold — I want to say a Duster or a Galaxie 500,” Viecelli recalls. “They drove the whole tour, all over the whole country, in that. And the gear was strapped to the roof, including Jim's drums, which were then exposed to the elements the whole tour: heat, rain, all of it. So they gradually were destroyed over the course of the tour.”

Looking back on his various experiences on the road with White over the years — both co-billing with Dirty Three and featuring the drummer in his band — Will Oldham (a.k.a. Bonnie “Prince” Billy) notes a similarly lax attitude toward the logistics of travel.

“We would go on tour and he would have this suitcase full of, like, books and rocks and junk and then just wear the same shirt and suit every day, and the same dress shoes,” Oldham recalls with obvious amusement. “And if we were going to go for a hike, he would just go for a hike in his dress shoes and his suit and his pink button-up shirt.”

Nastanovich recounts a time when he, White and Ellis took in some local culture in Barcelona before their bands shared a bill there. “I remember, after a brief soundcheck for both Pavement and Dirty Three, Jim realized that there was live bullfighting, corrida de toros, across the street,” he says. “It was a very memorable day because the three of us, Jim, Warren and myself, went over for about an hour and a half and had this amazing experience — a gruesome one, to an extent — watching bullfighting.”

Continents and years apart, Dirty Three still resonates

Within the band, the adventure was, and continues to be, the music itself. Turner, who worked in a slew of bands prior to Dirty Three, including the live-wire art-punk act Venom P. Stinger, which featured White behind the kit, recalls feeling an instant spark when the trio convened.

“It was the most exciting musical project I’d ever been involved with, for sure,” he says. “It was so open and creative, and I think we were just lucky that musically we all clicked. It’s not that common to just start playing music with people and it just works for you.”

On later releases, including the gritty, crackling Horse Stories and the forlorn, almost unbearably lovely, Steve Albini–recorded Ocean Songs, the group’s sonic tales unfolded like a wondrous fever dream — sometimes melancholy, sometimes ecstatic — while on 2000’s Whatever You Love, You Are and 2003’s She Has No Strings, Apollo, they sprawled out with an elegiac splendor.

Cinder, from 2005, found them streamlining their compositions and, for the first time, adding voice on a pair of enchanting tracks, one featuring a wordless turn from The Mekons’ Sally Timms and one with vocals and lyrics from avowed Dirty Three superfan Chan Marshall, a.k.a. Cat Power. In the Dirty Three documentary, Marshall professed an “addiction” to the band, citing the intense emotions they stirred in her. “I was just completely shocked that they would have a vocalist,” she said of being asked to collaborate with them, “and so honored.”

Aside from 2012’s Toward the Low Sun, the roughly two decades since have been relatively quiet for the group. But as Will Oldham points out, the DNA of the Dirty Three has persisted in the members’ various other pursuits.

“Each of their personalities and their musical personas or projects or trajectories or entities is fully present in each moment, so that each thing that each of them does separately is connected to and points back to, and forward to, what they do together as the Dirty Three,” Oldham says. “We were all introduced to Jim and Mick and Warren through the Dirty Three, and then everything they do after that, the Dirty Three resonates in all of it.”

Hearing them reunited on Love Changes Everything feels especially potent and poignant. Each track on the record is its own kind of gem: the rising-from-the-muck avant-rock of part I; part III, with its floating, impressionistic vibe; the soothing free-jazz-like swell of part VI.

“We haven't made a record for — whatever it is — 10, 12 years,” Ellis says. “We've all made lots of records between that, so it's not like the thirst to create had disappeared. I mean, we've all been really busy: Mick's been painting, Jim's been touring, playing, making records, and I have, and that's just all grist to the mill. I think we're really lucky in that respect. It's been great for the band.”

These days, the musicians keep up with one another, but in a seemingly hands-off way.

“I sent you my record, didn’t I, Warren?” White asks Ellis of his new solo effort, All Hits: Memories.

“Yeah, you did,” Ellis answers with a tone that suggests that the two hadn’t yet made a point of discussing what he’d thought of it.

“We don’t stalk each other,” Turner adds with a laugh.

That’s probably because they know intuitively that what they had in the beginning — the risk, as well as the reward — will always be there.

“We couldn’t have made this record 30 years ago,” Ellis says of Love Changes Everything. “It was just a trust in getting in the room and playing and seeing what would happen.”