Section Branding

Header Content

8 things to know about the drug known as 'gas station heroin'

Primary Content

Decades before it became known as "gas station heroin," tianeptine was prescribed to treat depression in dozens of countries. Now, U.S. poison control centers are reporting a dramatic spike in cases involving tianeptine — a drug that isn't FDA approved, and one that authorities warn poses overdose and dependency risks.

Tianeptine inhabits a murky space in U.S. drug regulation. It's illegal to market or sell the drug, but it's also not on the list of federally controlled substances. And while it's in products sold at gas stations and other stores, it's also available to buy online.

A growing number of states have now banned tianeptine, most recently, Florida. But millions of people in Europe, Asia and South America have used the drug — despite the fact that for years, no one was sure exactly how it worked.

"This is kind of a mistaken identity type of drug," Todd Hillhouse, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay who studies antidepressants' mechanisms and history, told NPR. "And it's kind of wild."

The drug's true identity emerged after researchers figured out it's a type of opioid — one that does, in fact, work in a way that's similar to heroin. Another similarity? People who abuse tianeptine report that it has left them wrestling with addiction.

Here's more to know about tianeptine and its unusual history:

It's available in the U.S., despite lack of FDA approval

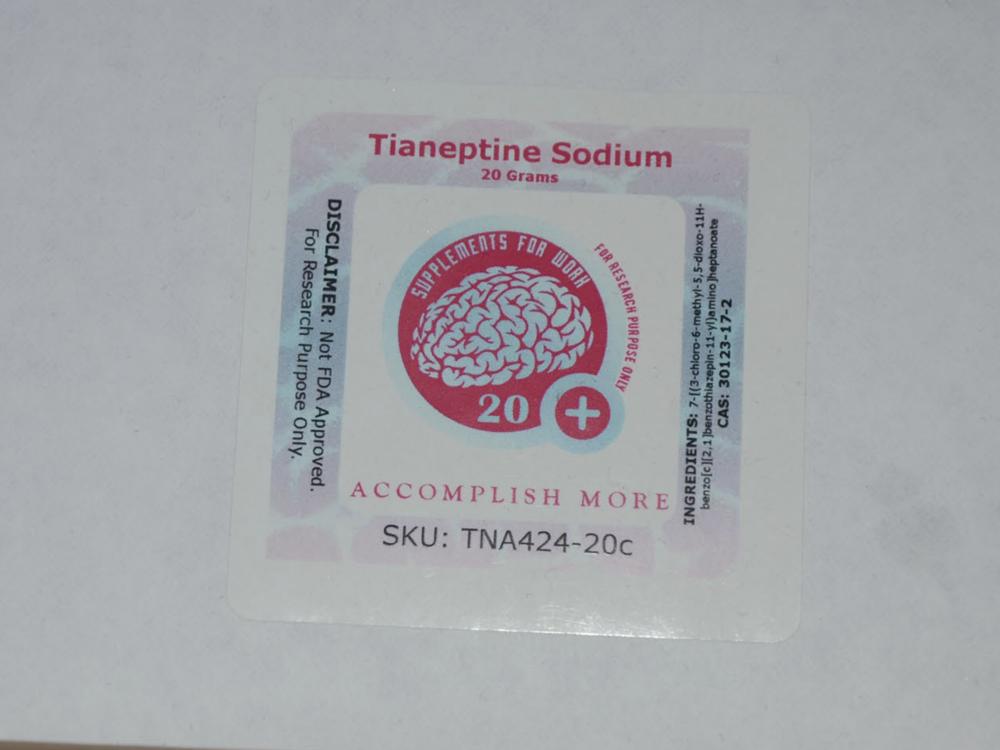

Launched in Europe in the 1980s, tianeptine has never been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for medical use. It's sold in the U.S. as a nootropic, a substance promising to enhance users' mood and cognitive function.

Experts warn that it's dangerous to consume any unapproved drug, particularly one that poses the risk of dependency and withdrawal, and that in the case of tianeptine, can cause respiratory depression and severe sedation. Often packaged in colorful, shot-sized bottles, these rogue tianeptine products contain the drug in varying concentrations and have also been found to include dangerous synthetic cannabinoids.

"Imagine if you're [at a] truck stop, you take two bottles of that and you're driving down the road — now you're high on opioids," Hillhouse says. "It's not a safe situation to be in. And it could be accidental. So I think it's good to get this out there and keep people vigilant. Just because you see it in a gas station doesn't mean it's safe."

People who use more pure forms of tianeptine often face another danger: addiction. A Reddit forum for people trying to quit the drug many of them call "tia" has grown to some 5,500 members. They describe taking full grams of the drug each day — in some cases, more than 100 times the manufacturer's recommended daily dose.

It was developed in France

In the late 1980s, Tianeptine gained its first market approval as an antidepressant: in France, where it was sold under the trade name Stablon.

The drug eventually spread to at least 66 countries, sometimes under the trade names Coaxil and Tatinol. Its recommended dose was small — one 12.5 mg tablet — and because the body clears it quickly, doses were to be taken three times a day. It also was advertised as having minimal side effects.

Tianeptine came out as Prozac was becoming a sensation, bringing a new era of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor drugs, or SSRIs. Tianeptine was lumped in with older drugs called tricyclics.

"Its chemical structure has three rings, so people thought that it was a tricyclic antidepressant," Jonathan Javitch, a professor at Columbia University and a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute who is an authority on tianeptine, told NPR.

The drug worked, but no one knew how

Researchers soon realized tianeptine didn't seem to work like any other antidepressant. Even in 2012 — 25 years after its initial authorization — France's Transparency Committee, an advisory panel that assesses medicines for the government, described tianeptine as "an antidepressant, the exact mechanism of action of which is not known."

Both tricyclics and SSRIs work by targeting receptors for neurotransmitters such as serotonin, aiming to block neurotransmitters from being reabsorbed so they can boost levels of our bodies' key behavioral and mood regulators. But in tests, tianeptine didn't attach to those receptors.

"It didn't work at a whole variety of receptors," Javitch said. "And it was basically a mystery of how this compound worked."

Hillhouse of the University of Wisconsin compares it to having a key that fits a lock — but not knowing which lock the key opens.

It showed promise of broad benefits to the brain

Tianeptine caught Javitch's eye about 10 years ago, after a colleague at Columbia, Dali Sames, suggested they take a look at the drug. Studies had suggested it can improve memory and ease anxiety and bring other benefits.

Javitch's interest grew when he saw research by the late scientist Ben McEwan, outlining the drug's seeming "neurorestorative" ability to correct damage in the brain. Tianeptine was described as modulating one of the major neurotransmitters in the brain and promoting neuroplasticity, the brain's vital ability to adapt.

"This antidepressant is rich in future possibilities," both for its own application and to improve our understanding of depression, McEwan and his fellow researchers wrote.

A 'shocking' breakthrough showed it worked like an opioid

In their work, Javitch, Dali and their colleagues found that tianeptine targets the mu opioid receptor, which is named for morphine and controls pleasure, pain relief and need. The finding was shocking, Javitch said, given the ongoing opioid crisis. Even more surprising: Tianeptine didn’t just bind to the opioid receptor.

"It actually activates the receptor like other opioids do, like morphine or like oxycodone or like fentanyl," Javitch said.

They were also shocked because it's not the way other antidepressants work — and at the time of their research in 2014, there were few signs of tianeptine abuse, Javitch said.

The researchers’ findings brought a swirl of competing emotions. They were excited to discover a unique antidepressant mechanism — but they were also well aware of surging opioid addiction in the U.S. Their hopes for the drug's future were immediately tempered.

Since then, Javitch and his colleagues have been working to synthesize analogs for tianeptine, hoping to isolate its potentially beneficial properties from its potentially harmful ones.

"I'm not cavalier about it," he said. "I don't think it should be sold in gas stations or over the counter. But I think that it does have scientific and medical therapeutic potential."

But it's also upsetting, Javitch said, that reports of abuse rose after his team published their findings in 2014.

Abuse, and calls to poison centers, have risen

Even before the opioid link was confirmed, people were beginning to abuse tianeptine.

In 2007, Stablon added a warning that patients with a history of addiction should be closely monitored. And in 2011, French officials found a small subset of patients were "deviant users of tianeptine," meaning they were far younger than the median age of 57; were taking an extremely high estimated daily dose of 540 mg of the drug; and were "shopping" for tianeptine, using multiple doctors and pharmacies each month.

France imposed new restrictions, putting tianeptine under narcotics regulations and limiting prescription length.

In the U.S., emergency calls about tianeptine spiked after the opioid findings emerged. From 2000 to 2013, the National Poison Data System received an average of less than one call a year about tianeptine exposure, according to the CDC. But dozens of calls began to come in after 2014, and cases have continued to rise, with 391 calls about tianeptine to U.S. poison centers in 2023, according to America's Poison Centers, a nonprofit that partners with the CDC and state agencies.

"This increase in voluntary reports to poison centers serves as a strong signal that use of this substance is on the rise in the U.S.," the organization said in a message to NPR.

From 2000 to 2017, the National Poison Data System reported that 82% of tianeptine calls involved men and that nearly 57% of calls involved people aged 21-40.

The flood of stories about its habit-forming properties are another sign of tianeptine's spread. In the Reddit forum about quitting the drug, people who describe themselves as former heavy users of opioids say tianeptine is as addictive, if not more, than other drugs they’ve used.

Tianeptine withdrawal has been documented since at least 2017, when Yale clinicians described "a significant withdrawal syndrome" in a 36-year-old patient who was trying to quit the drug. The man bought the drug online and had been self-medicating his depression.

Several deaths have been linked to tianeptine

Last year, a cluster of calls to New Jersey's poison control center was traced to Neptune's Fix — a tianeptine elixir that also contains other compounds, such as cannabinoids — prompting the FDA to issue repeated warnings and send a letter to retailers urging them to stop selling any product with tianeptine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that 13 of 17 tianeptine patients in New Jersey were admitted to intensive care — with severe symptoms that could be due to potent cannabinoids and/or the effects of multiple drugs.

"To date, we have identified one overdose death that involved tianeptine in New Jersey," Michele Calvo, the New Jersey Health Department's director of opioid response, told NPR earlier this year. "However, tianeptine was not implicated as a cause of death for this case (the case involved multiple other substances that were implicated in the cause of the death)."

The first known tianeptine fatalities in the U.S. occurred when two men died after ordering tianeptine powder online, according to a 2018 study.

The family of an Ohio man who died after taking Neptune's Fix recently filed a wrongful death lawsuit. In Texas, the parents of a man who died after taking tianeptine in 2015 sued online retailer Powder City; the company said it was halting its business soon afterward.

U.S. authorities try to crack down

Lack of a federal ban on tianeptine has meant states have been acting on their own. In 2018, Michigan became the first state to ban sales of the drug, classifying it as a Schedule II controlled substance, the same category as drugs like cocaine and fentanyl. The FDA says at least 12 states have enacted similar bans, which includes products such as Neptune's Fix and prohibits retailers from shipping to those states.

When contacted by NPR, an FDA spokesperson noted that all sales of tianeptine are illegal in the U.S., because the drug hasn't been approved for any medical use. They said the agency is "working with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to help stop imports of tianeptine."

In February, two separate federal cases involving tianeptine sales online resulted in the forfeit of a combined $4.2 million. In one of those cases, Ryan Stabile of Pasadena, Calif., was sentenced to two years in prison. In the other, Nootropics Depot CEO Paul Eftang was ordered to serve probation.

Bipartisan legislation to federally classify tianeptine as a Schedule III drug was introduced in Congress earlier this year. The House bill would place the drug in the same category as ketamine, anabolic steroids and some codeine preparations. It has lingered in committee; its backers say they'll keep fighting for the bill.

But there are signs that even if efforts to keep the drug out of stores succeeds, tianeptine has already become part of the nation's struggle with opioids.

The Drug Enforcement Administration said this year that law enforcement agents have found tianeptine powder in bulk. Drug dealers have used it to make counterfeit hydrocodone and oxycodone pills, the agency said, or to fill baggies made to resemble heroin packages.