Caption

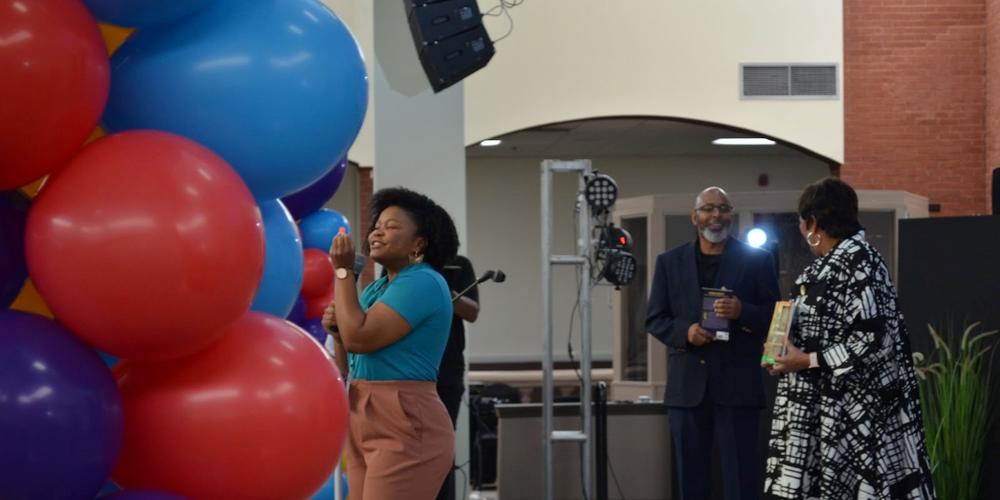

Fayron Epps speaks in April 2024 to conference attendees at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Credit: Pamela Kirkland/GPB News

LISTEN: Black Americans are about twice as likely as White Americans to suffer from Alzheimer's Disease or other dementias. One program aims to reduce the stigma of dementia and better equip the faith community to serve those most in need. GPB's Pamela Kirkland has more.

Fayron Epps speaks in April 2024 to conference attendees at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

The Black church has long been more than just a place of worship. For some, it’s a beacon of hope, community and resilience. A place where generations have gathered for guidance and healing.

More recently, as the rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease have risen, particularly among Black Americans, a new challenge has emerged.

Older Black Americans are about twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s or other dementias as older white Americans, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. While only 35% of Black Americans say they’re concerned about neurocognitive diseases, 65% say they know someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia.

Yet, awareness and resources to address these diseases within the Black community have often lagged behind. That’s where Alter Dementia steps in.

Alter Dementia equips Black churches with the tools and education to better support congregants living with dementia and their caregivers. Created by Dr. Fayron Epps, a nursing professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, the initiative has gained traction in Georgia and nationwide.

Destiny Christian Center International in Fayetteville, Ga., southwest of Atlanta, was one of the first churches to sign on with Alter.

Senior Bishop Glenn Allen Sr. has embraced the mission wholeheartedly.

“I was on the front end of Dr. Epps starting this whole, journey and it all started in my office with her trying to find out what she wanted to do in church,” Allen said. “I didn't know much about dementia and I didn't know much about how it affects families, especially caregivers. Then, as I grew in understanding … I became more and more interested — really tapping into our families like never before.”

Epps said bringing this support to the Black church, an institution deeply rooted in tradition, wasn’t an easy task. Growing that network of churches took time and trust.

“I'm not gonna say it has not been a challenge," Epps said. "It's just part of the process. How can you be receptive of something that you don't know about?”

Alter created a slew of recommendations for the church to implement: shorter services, using familiar prayers and hymns, and visual aids to follow along during service. But while Epps said it can be tough asking your pastor not to preach for so long, getting the churches on board didn’t take long.

Panelists at the Black Dementia Minds discussion talk about living with neurocognitive disorders. Terry Montgomery sits in the center of the panel.

“It was listening to me and, I think, persistence," she said. "And then really seeing that I was on assignment and it wasn't about me: It was about serving the community, serving the people, then they became receptive.”

The persistence paid off. This year, Alter hosted its first annual summit in Decatur, Ga., just east of Atlanta. The summit brought together the 80-plus churches from around the country, with the majority of churches from Georgia, that are already part of Alter's network.

It also was a space for people like Terry Montgomery, who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s at 58 years old.

“It’s an opportunity, while I have time and still know 'who's on first,' to share what this journey has been like and how Alter has created an atmosphere for people to come to church again,” she said.

Montgomery spoke on a panel called “Black Dementia Minds,” which hosted a variety of speakers sharing insights about living with neurocognitive disorders.

She said it was especially important to have the church become a place where the community can learn more about dementias.

“You come to church to fellowship, to exchange information, to network with one another, to see a testimony of a person that once could not walk, another person that could not talk,” Montgomery said.

The initiative also extends its reach to those who often bear the heaviest burden: the caregivers. Roz Tandy, the executive director of a nonprofit called It’s You AND Me, understands this role all too well. Having cared for two aunts with dementia and later running a personal care home, Tandy knows firsthand the toll caregiving can take.

“Burnout just really snuck right up on me,” Tandy recalls. “The stress of it, the frustration, sometimes, the anger, all of that. One of the things that I enjoyed doing with the caregivers that I work with, we keep it very real.”

Tandy emphasizes that churches must do more than offer prayers; they must provide real support.

Congregants join hands during church service at Destiny Christian Center International in Fayetteville, Ga.

Scenes of Sunday service at Destiny Christian Center International, a nondenominational church in Fayetteville, Ga.

Conference attendees listen to presenters at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Conference attendees listen to presenters at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Fayron Epps speaks to conference attendees at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Bishop Glenn Allen Sr. delivers his sermon during services at Destiny Christian Center International, a nondenominational church in Fayetteville, Ga.

A woman raises her hands during church at Destiny Christian Center International in Fayetteville, Ga.

Dr. Fayron Epps watches services at Destiny Christian Center International, a nondenominational church in Fayetteville, Ga.

Fayron Epps speaks in April 2024 to conference attendees at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Panelists at the Black Dementia Minds discussion talk about living with neurocognitive disorders. Terry Montgomery sits in the center of the panel.

A presenter speaks at the inaugural Alter Dementia Summit in Decatur, Ga.

Bishop Glenn Allen Sr. presents to a conference attendees about how churches can better cater to congregants with neurocognitive disorders and their caretakers.

“We have to be careful telling people, ‘Just pray about it,’" Tandy said. "You have to put feet and wings on those prayers. You see a caregiver coming into church. They may be smiling, they may have their loved one dressed so nice. You have no idea what it took for them to get there.”

Epps agrees.

“We want to bring hope," she said. "We already know that when you hear Alzheimer's disease or dementia, a lot of doctors, when they give that diagnosis, they say, 'Go get your affairs in order.'"

"It's a culture change, and that's what we're trying to create here. And I'm not going to boast, but I think we may be getting there.”