Section Branding

Header Content

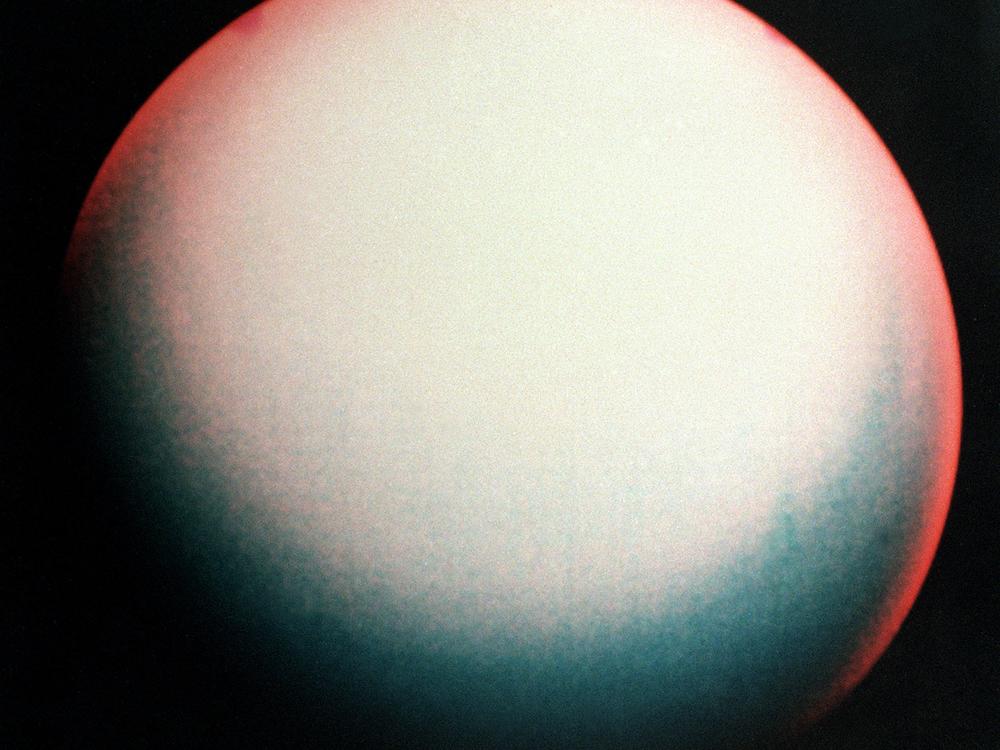

Opinion: Uranus was having a bad hair day. Hey, it was the '80s!

Primary Content

Uranus wasn't ready for its closeup 38 years ago.

I speak of the 7th planet from the Sun, and third largest in our solar system, which received a flyby — 50,000 miles above the planet — from the Voyager 2 spacecraft on January 24, 1986.

Scientists declared that detailed photos snapped during that five-hour pass by the planet and its icy moons revealed that Uranus was different from other worlds in the outer solar system. They said its magnetic field didn't hold any of that hot, glowing, gas known as plasma.

But a study this week in the journal Nature Astronomy says scientists have now determined that the flyby occurred at a time of an increase in solar wind activity that rarely occurs. This caused the planet's magnetosphere to shrink.

"If Voyager 2 had arrived just a few days earlier, it would have observed a completely different magnetosphere at Uranus," says Jamie Jasinski, a physicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who was lead author of the study. "The spacecraft saw Uranus in conditions that only occur about 4% of the time."

In other words, Uranus was having a bad hair day.

Incidentally: NPR's Research department says that when the planet was discovered in 1781, the astronomer William Herschel tried to have it named after King George 3rd. A planet called George might have been a little easier to talk about on the radio than one named after that particular Greek god.

As it passed by the 7th planet, the spacecraft also zipped by 10 previously undetected Uranian moons, and two Uranian rings. And Voyager 2 is still out there — waaay out there — in interstellar space.

Dr. William Dunn of University College London says this new determination that Uranus was beset with solar activity during Voyager's brief flyby, 38 years ago, gives him fresh hopes.

"The Uranian system could be much more exciting than previously thought," he told the BBC this week. "There could be moons there that could have the conditions that are necessary for life, they might have oceans below the surface that could be teeming with fish!"

The new thinking might remind us that not only do we constantly learn new things, but the things we thought we knew for certain can change as we learn more. Another Uranus mission may be launched for a closer look in the early 2030s. In the meantime: maybe we shouldn't judge a planet — or a person — in a single glance.