Caption

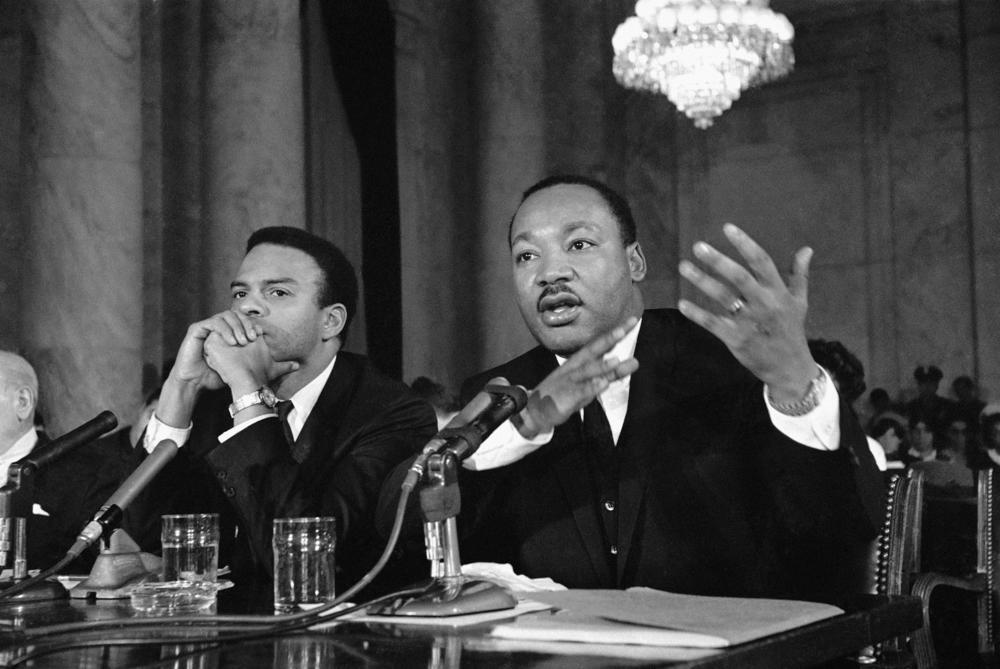

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., president of Southern Christian Leadership Conference, testifies Dec. 15, 1966, before a Senate Government Operations Subcommittee studying urban problems and poverty. The Rev. Andrew Young sits at left.

Credit: AP file photo