Section Branding

Header Content

They Found It! The Long-Lost Album By Zambia's President: 'We Shall Fight HIV/AIDS'

Primary Content

The late Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda knew that speeches were not the only way to deliver messages. He was known for making statements through songs – like the 11 tracks on his 2005 album We Shall Fight HIV/AIDS.

In the first cut, "Nkondo (This Is War)," he half-sang, half-chanted in his folksy, unvarnished baritone, alternating between the local language Bemba and English: "Children of Africa ... Remember, prevention is better than cure. Remember, abstinence is a service to God. If you can't abstain, remember to use a condom."

The gentle, danceable songs delivered a message that is still relevant (although the idea of abstinence as a sole preventive measure has been sharply criticized).

But the album seemingly vanished without a trace – until a nonprofit organization and group of young musicians decided to search for it to bring back the president's urgings on combating HIV/AIDS.

A man with a bike, a guitar and a message

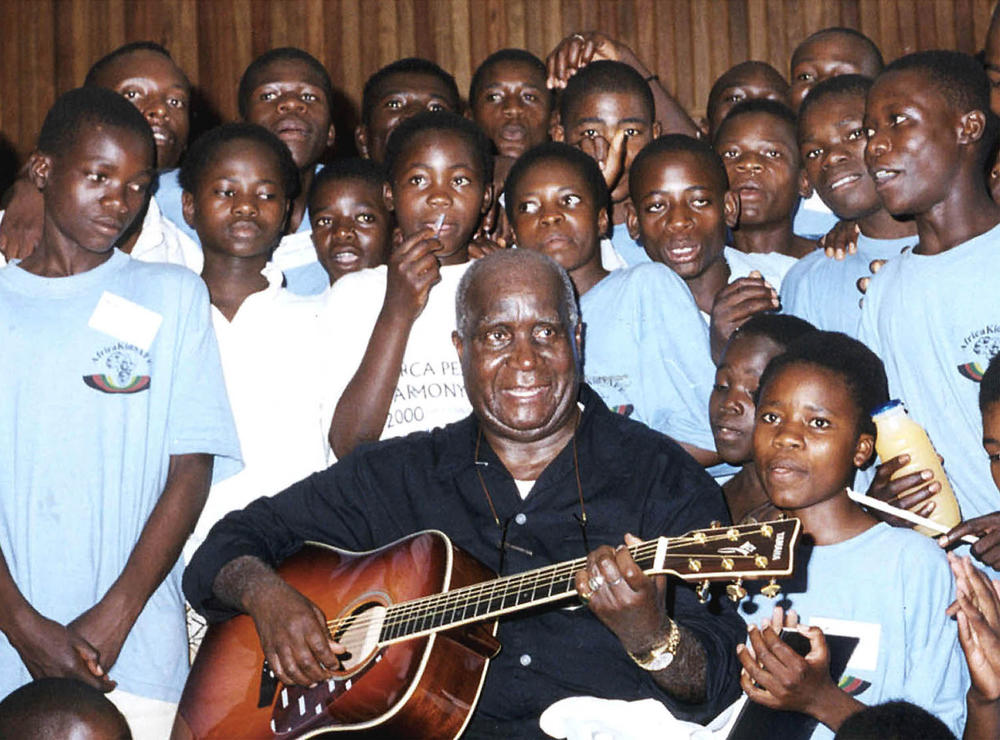

Kaunda was always a different kind of revolutionary. In the early 1960s as he led Zambia's freedom movement from the British, the guerrilla leader could be seen riding around the countryside on a bicycle and armed with a guitar. Throughout his term, numerous photos show him bringing that instrument on international visits. The strong geniality in his voice can be heard today on various YouTube posts.

"As an artist, Kenneth Kaunda was a very honest person," Zambian singer Victoria Wezi Mhone said. "He wasn't singing for commercial appeal, it sounded like a prayer. That's what I love about him."

Music remained part of why Kaunda was revered among many in Zambia, which he led from its independence in 1964 until he was voted out of office in 1991. He continued singing until shortly before his death on June 17 at the age of 97.

Katy Weinberg, co-founder of the organization UkaniManje ("Wake Up Now" in Nyanja), read about the album 15 years later and thought that Kaunda's music could be of great help to her NGO's mission of using music to raise greater awareness of the disease, especially because of Kaunda's reputation for unbridled emotional displays.

"We found this one Reuters article [from 2007] that was talking about how Kenneth Kaunda recorded this album and had been known as the weeping, singing president," Weinberg said. "That was the only information I could find on it anywhere on the Internet. I was asking around the country and when I asked the musicians, everyone sort of remembered the songs but no one had the album or knew if [copies] existed."

The album was personal for Kaunda. His son Masuzgo died of AIDS in 1986 and shortly afterward the president became one of the first African leaders to publicly acknowledge the epidemic — despite its rapid spread throughout the continent. His openness earned him admiration for years after he held public office. Emmanuel Makasa, a physician who advises UkaniManje, says that Kaunda's honesty was his strength.

"HIV was associated with shame, a shameful disease that was stigmatized, patients didn't want to talk about it," Makasa said. "Someone in Kenneth Kaunda's own house died from it. That encourages others to come out. Talking openly about sexuality, [the] act of having sex is taboo, we don't talk about it openly but the disease was transmitted because of what was happening. You have to describe the whole sexual act and it took courage. Kenneth Kaunda helped with that."

About three years before Kaunda recorded We Shall Fight, The New York Times depicted him as an elder sage. Not wanting to re-enter the political arena, he said that he was, "running a foundation now, fighting HIV/AIDS to the best of my ability. In my free time, I play some piano. I sing some hymns."

This persona, and his music, was what another UkaniManje co-founder, singer Ephraim Mutalange [a.k.a. Ephraim Son of Africa], recalled when he met Kaunda prior to his wife's death in 2012. "I was privileged to be part of the singers that graced him on his wedding anniversary before his wife Betty died," Mutalange said. "He would hold a white handkerchief and use it to bless people and say, 'You'll be an old man and be influential.' We used to love to go there to get his blessing. He would get his guitar and play for his wife and I learned how to sing a love song from him."

The lost album is found

UkaniManje wanted to present that spirit when they heard about the album last spring. Through online searches and conversations, Weinberg and her staff tracked down a rare copy of the CD from a collector who lived a 10-hour drive from Zambia's capital, Lusaka. They had hoped to interview Kaunda and his family but his death from pneumonia curtailed that part of the project.

Now the organization hopes to remaster the original album and is also asking current artists to record the songs, whose rhythms that would sound familiar to fans of southern African pop. Kaunda recorded it as a collaboration with producer Rikki Ililonga, who had became known for his pioneering role in 1970s Zambian rock (a.k.a. Zamrock) and also composed most of the disc's material.

Asked about Kaunda's reference to abstinence, Weinberg noted that he also refers to the use of condoms: "We are promoting the ability for people to make choices about their sexual activity without saying the cut and dry 'abstinence' is the way."

Ethnomusicologist Jason Winikoff describes the songs as lyrically direct — and also representative of the linguistic and stylistic mixtures of a country where more than 70 languages are spoken. This inclusive approach was Kaunda's dream. As Wezi said, "We have 72 tribes, 10 provinces, different people with different dialects, different beliefs, cultures, traditions, but he made this one Zambia model for our nation. He was the guy who said, 'No tribalism.' He was the unifier."

As for the sound of the album, "some songs are heavily influenced by reggae, others are a little more rock, or Zamrock," said Winikoff. "Some are more pop, gospel. There is not really a lot of traditional stuff going on, but it's an influence inherently. The album is a microcosm of some of the sounds you hear in the Zambian music scene. It's got a lot of influences and if it could spread, it can be really effective. And it's catchy."

The album's message also remains relevant. Globally, 1.5 million people were infected with HIV in 2020. While Zambia has made progress in bringing down the number of annual infections, there were 51,000 new cases in 2019. About 12% of Zambia's adults are infected with HIV, the the eighth highest rate in the world.

Zambia is also a youthful nation with a median age of 17. So part of UkaniManje's mission is to invite young popular Zambian singers to send a message about HIV prevention in musical styles that bring in their backgrounds in contemporary gospel and R&B.

Many of these artists also have reputations for using their music to raise awareness of social issues. Wezi, who has sung about gender-based violence prior to her collaborations with UkaniManje, is working on a new song for this organization, the Nyanja-language "Moyo Nimukwatu," calling for Zambians to reject superstition and take advantage of modern medicine.

"I agree with the idea of borrowing from the past," Wezi said. "What I am looking at doing with Kenneth Kaunda's music is pay tribute to his artistry, stay true to that, to honor him using my sounds. I don't know if I can call it a cross pollination, it's what I love about his work and mashing it up with what I do."

Mutulange and singer Abel Chungu are also contributing new songs and selecting Kaunda compositions to interpret for the album remake. Chungu mentioned losing some family members to AIDS and how moved he was when singing at a wedding for a couple who got married — the groom was HIV negative and the bride was HIV positive.

"We all picked specific topics and directions we wanted to share as artists," Chungu said of his participation in the project. "I wanted to share that it is most important and powerful when you choose love over everything. The message Kenneth Kaunda was sharing was, 'Let's not stigmatize people who have [HIV], anybody can have it, so we must show love to everybody.' We're all united on this issue, we're all speaking one voice — that this needs to come to an end and we can do something about it."

Aaron Cohen is the author of Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power (University of Chicago Press) and Amazing Grace (Bloomsbury). He teaches humanities and English composition at City Colleges of Chicago and regularly writes about the arts for such publications as the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Reader and DownBeat.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.