Section Branding

Header Content

Beyond Plexiglass: Scientists Say This Simple Solution Could Keep VP Debate Safer

Primary Content

In a bid to protect the candidates from the coronavirus, the stage for Wednesday night's vice presidential debate in Salt Lake City will feature plexiglass barriers between Vice President Pence and Democratic Sen. Kamala Harris of California. Concerns about viral spread are heightened in light of the outbreak in the White House.

But as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledged this week, the virus can spread through the air. Given that fact, scientists say plexiglass barriers alone may not be enough protection if one of the candidates is infected and exhaling virus. Though it's unclear what other precautions the debate commission may be implementing, some researchers are suggesting a simple solution: Put a localized air cleaning device right next to the candidates.

"The problem is that a plexiglass barrier does not block aerosols; it only blocks spray," says Donald Milton, an infectious disease aerobiologist at the University of Maryland School of Public Health. While plexiglass can block respiratory droplets coming from the candidates' mouths, that kind of spray is more of a concern when people are within about 6 feet of each other, he says.

But the vice presidential candidates will be more than 12 feet apart onstage at the University of Utah, and at that distance, "what's going to get you is aerosols," Milton says. Those are tiny airborne particles that are generated when we speak, sing, cough or breathe, and they can float around a partition, farther than 6 feet. If there's not enough ventilation in a room, they can build up. "That's what we are concerned about," he says.

Jelena Srebric, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Maryland, says, "The best way to really protect people is to remove viral particles at the source." Surgical masks work, because they would help block some of the aerosols generated when people talk. But as Milton notes, masks are not ideal in a debate setting, in part because some of the audience may be lip reading.

That's where box fans come in.

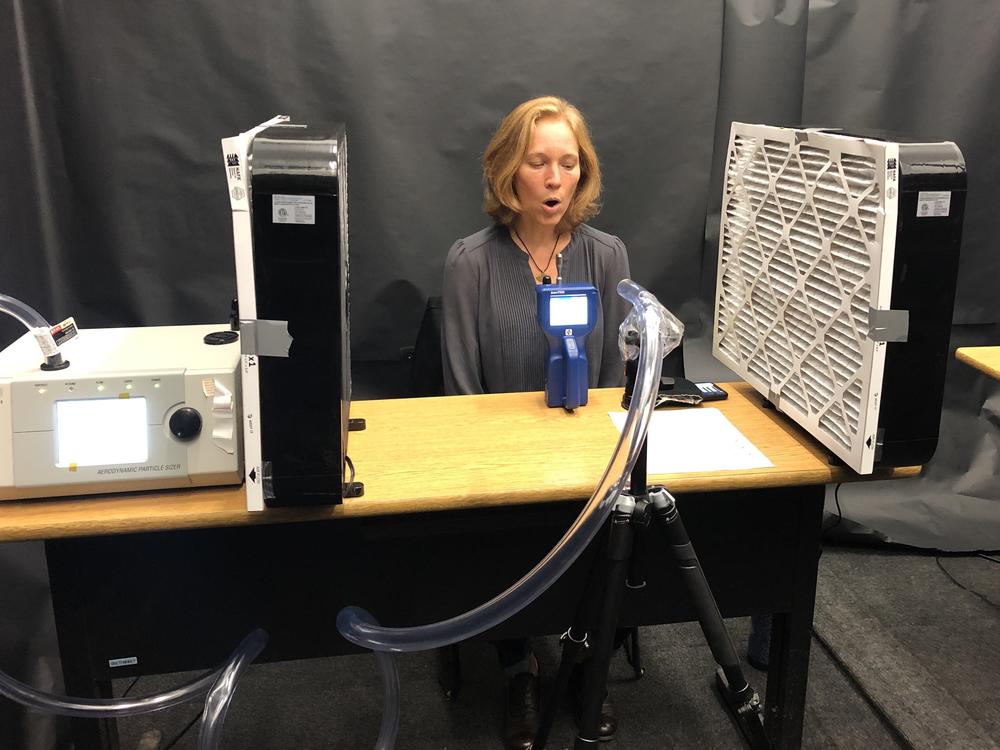

A simple, cheap, store-bought solution using HEPA air filters duct-taped onto box fans could dramatically reduce the amount of virus that accumulates in the air, Milton and Srebric say.

The idea, they note, originated with Richard Corsi, an indoor air quality expert at Portland State University. Basically, you take a box fan and duct-tape a HEPA air filter to the front of it. Then you place a fan on either side of the speaker. One box fan would be blowing toward the speaker, while the other fan would be blowing away from the speaker.

"The idea is that you can clean the air that is coming towards you, so you remove as much particles as possible with the HEPA filter and fan that is coming to you. And then as you're breathing out, another fan and HEPA filter takes your air in" to filter it, Srebric says.

Srebric and Milton tested this setup last week using choir singers, and they found it could reduce the concentration of particles in a room by 50%.

The researchers have contacted the presidential debate commission and both presidential campaigns to recommend they adopt their duct-taped box fan and filter contraption onstage.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.