Section Branding

Header Content

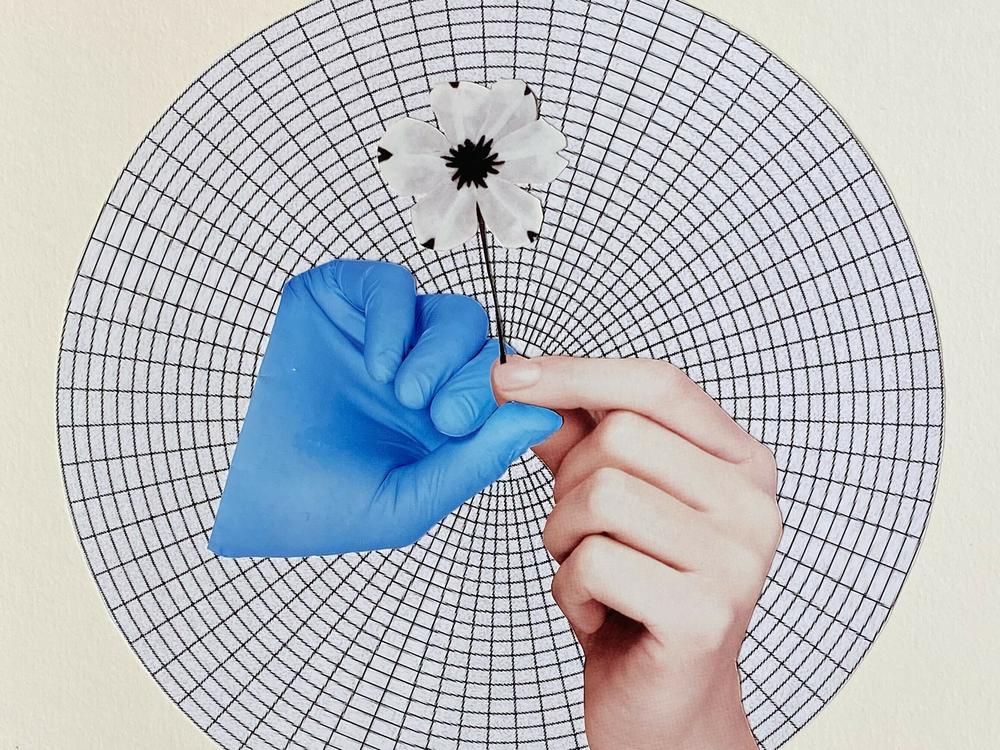

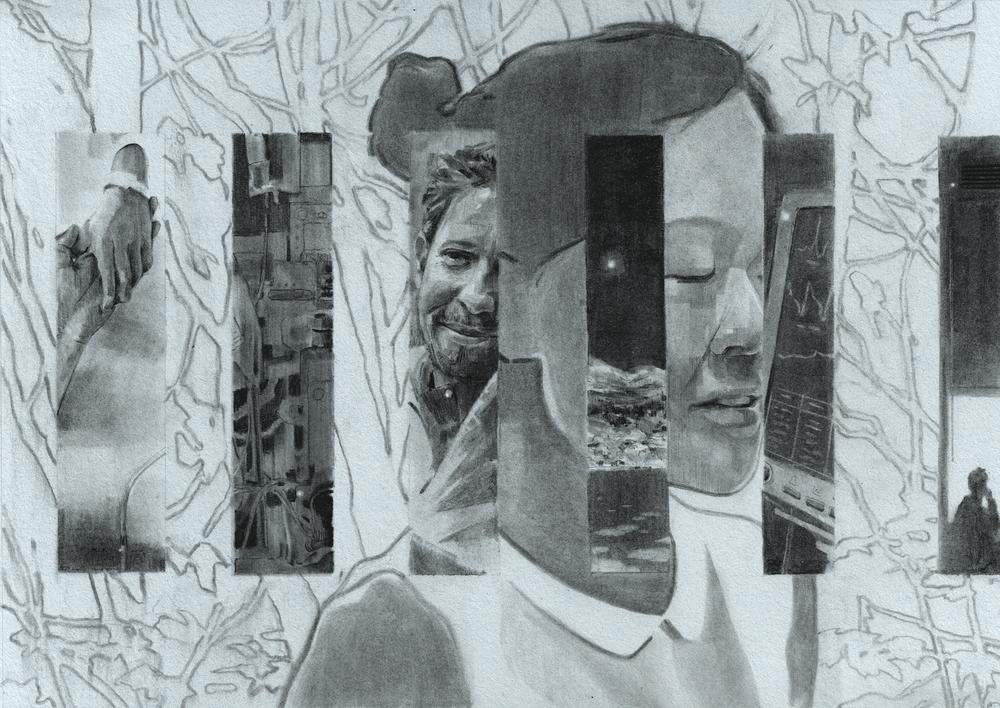

Could creativity transform medicine? These artists think so

Primary Content

In 2016, Emily Peters became, as she puts it, a "statistic in the maternal health mortality crisis." While giving birth to her daughter, she had an amniotic fluid embolism, a rare and life-threatening complication that landed her in the intensive care unit.

Peters eventually recovered. But she says she was disturbed by the dysfunction she witnessed during her hospitalization, "all these little cuts that are so demoralizing." For instance, her healthy newborn daughter was discharged from the hospital while Peters remained in ICU care — she and her husband had to pay for a private nurse so they wouldn't be separated from their days-old infant.

Peters, who works as a health care brand strategist, decided to work to fix some of what's broken in the American health care system. Her approach is provocative: she believes art can be a tool to transform medicine.

Medicine has a "creativity problem," she says, and too many people working in health care are resigned to the status quo, the dehumanizing bureaucracy. That's why it's time to call in the artists, she argues, the people with the skills to envision a radically better future.

In her new book, Artists Remaking Medicine, Peters collaborated with artists, writers and musicians, including some doctors and public health professionals, to share surprising ideas about how creativity might make health care more humane.

"It is about creating this very desperately needed culture change," Peters says. "It's hard to hope right now ... you have to practice hoping, you have to practice imagining a better system."

For example, the book profiles electronic musician and sound designer Yoko Sen, who has created new, gentler sounds for medical monitoring devices in the ICU, where patients are often subjected to endless, harsh beeping.

It also features an avant-garde art collective called MSCHF (pronounced "mischief"). The group produced oil paintings made from medical bills, thousands and thousands of sheets of paper charging patients for things like blood draws and laxatives. They sold the paintings and raised over $73,000 to pay off three people's medical bills.

It's similar to a recent performance art project not profiled in the book: A group of self-described "gutter-punk pagans, mostly queer dirt bags" in Philadelphia burned a giant effigy of a medical billing statement and raised money to cancel $1.6 million in medical debt.

Peters says that's the kind of work she wants to highlight: edgy and a little bit weird. It's easy to become jaded about health care costs, she says, but art can make the activism come alive, "so that we keep that topic high on our outrage list."

There's very little in the way of policy prescription in this book, but that's part of the point. The artists' goal is to inject humanity and creativity into a field mired in apparently intractable systemic problems and plagued by financial toxicity. They turn to puppetry, painting, color theory, and music, seeking to start a much-needed dialogue that could spur deeper change.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Mara Gordon: What made you want to create this book?

Emily Peters: I think I'm always very curious why so many people – really the majority of everybody in any way involved in the health care system – feel so powerless. Physicians and surgeons and health care administrators and people who, to me, seem very, very powerful, [they] feel very powerless. And so the book came about as thinking about power and change. And then I realized that artists have this unique intersection where they are very powerful, they bring a lot of the things that were missing in health care, trying to build a better future.

MG: What is it about art that feels like a tool to challenge that feeling of powerlessness?

EP: The very first person I interviewed for the book was a photographer, Kathleen [Sheffer], who was a heart-lung transplant survivor. She used her camera in the hospital to try to be seen as more powerful, to be seen as a full person by these very fancy transplant surgeons who are whisking in and out of her room, viewing her as just a body. I saw that she had gained that power through being an artist.

I had another conversation with a physician out of New York, Dr. [Stella] Safo ... She said in our conversation: "I just feel like we don't even know what's possible." She really highlighted that there's this crisis of imagination. Everybody feels so demoralized that we can't even imagine what we want to ask for to make it better.

That's a creativity problem. And the people who are creative are artists. They are really good at sitting in complexity and paradox, and not wanting everything to be perfect, but being able to see things for what they are ... And really imagine. And so that was the hypothesis: Oh, there's something really interesting at this intersection between art and medicine.

MG: You had a traumatic experience giving birth. I'm so sorry to hear about it. Tell me a bit more about what went wrong when you were hospitalized, about the systems that didn't work correctly.

EP: There were so many places in that process where you started to see what's going wrong in health care.

It was a brand new, beautifully-built facility, but that had issues: People didn't know their way around the hospital. It's an academic hospital, so there were a lot of students and it can be sometimes chaotic. I actually asked for a different nurse, and the hospital said no. So that was not a good part of the experience, having my concerns be dismissed.

[There were many] little indignities ... Who decided these things? There's so much in health care that we just sort of feel stuck with, like "that's just the way it is."

Then it's so damaging for the people who are working there: the residents who are working 24 hours; the doctors who feel burned out; and the nurses who feel taken advantage of. We can't have a functional health care system if everybody involved is miserable.

MG: My favorite part of the book was the section where there's a color palette, named for different medical phenomena: pill bottle orange, Viagra blue. You talk in the book about how we could think more creatively about color in health care settings. But I think a lot of people in health care worry that too much color somehow distracts from the seriousness of medicine.

EP: So many of these things, somebody chose, and they didn't do a huge amount of research on it. They just chose it, and we take it as gospel now.

The white coat ceremony ... [I had thought it had started in] probably medieval Florence: they were putting white coats on medical students and welcoming them into the guild, it just feels like this ancient tradition. And it's something that was invented in Chicago in 1989. A professor was complaining that the students weren't dressing professionally enough.

That is not something that we necessarily have to carry with us. But it was also a good example of how somebody can create a change, and can create a new tradition, a new piece of our culture.

Same thing with the advent of the medical green, [the ubiquitous color of medical supplies]]. There's a spinach green that came from a surgeon here in San Francisco, just working to try to reduce eyestrain, but that became very standard in medicine. And then there's also a minty green, that a color theorist in Chicago just decided that that was the color for health care, that minty green was going to save us all and was going to look so beautiful.

As part of the chapter on color, we surveyed a couple hundred people [and published the results online]: "What colors would you want to see in the hospital?" I was expecting those soothing pastel tones. And it was totally different: it was neon purples and oranges and reds. Don't assume what people want. We have the technology and the capability now to build in systems that give people some control and some agency over things like color. LED lights are very affordable, and you can dial up exactly what color you want.

MG: I've really been acculturated to the idea that sterility is synonymous with professionalism. But there were challenges to that idea in the book – particularly the chapter on MASS Design Group, and the hospital in Butaro, Rwanda, that they helped design. So maybe there's hope that boring doctors like me can accept a little more beauty in our work environments.

EP: Hospitals have long had space for some art inside of them: some sculpture gardens, or a mural, or some art here and there. So there is a crack in the wall that is interesting to explore.

I think where it gets extra powerful is for the artists to be working with the physicians, with the patients. Thinking, truly, what does a healing environment look like? Talking about MASS Design, and what they were able to build. It wasn't just making a beautiful hospital, which they did, but using local artisans, and creating jobs for local people, and using local stone. Making it so that the hospital actually healed the community that it was serving.

MG: Has anyone told you that they think that health care is too important for art?

EP: I've heard the criticism that this is just about wallpaper on a pig: "You're talking about adding more sculpture gardens and increasing the cost of health care." I did not want it to be a book about creating more luxurious hospitals.

We have a crisis of financial toxicity, we have a crisis of outcomes. It's specifically a book about fighting those things, and finding a way to fight those things that feels possible and human ... There's real revolutionary potential for the use of art.

MG: You also had a really interesting chapter on how puppetry can help medical students learn to connect with their patients through creativity and spontaneity.

EP: Puppetry is a really interesting tool, not only to show how you empathize with a patient, but also to [think about] what's happening with your own body. What are you feeling right now? Where's your attention? Especially with young physicians in training. You're exhausted. You've been on your feet for a long, long time. How is that coming across in how you're presenting yourself? To the patient?

[Marina Tsaplina's work with] puppetry is a really eye-opening way to think about those things. That puppet is helping you think: I don't want to come in with my arms crossed ... or come in the room and be sitting on the stool and just immediately turning my back to the patient.

MG: Do you think medicine takes itself too seriously? Do we need more humor in health care?

EP: You're holding somebody's heart in your hand – this is a very intense job. You're trying to convince somebody to enter hospice – that is not easy. This is not an easy job. But that seriousness can feel almost like play acting and really inauthentic to people. That's where we see a lot of people starting to burn out and say: "Why am I here? Why am I pretending?" You're putting on this white coat: here I am, doing these motions, and it just feels very insincere.

And that's such a waste to me, because it is such a beautiful, incredible profession. We, as patients, also want you guys to be humans. We're on your side.

Carmel Wroth edited this story.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.