Section Branding

Header Content

The Story of the Jews: The Leo Frank Case

Primary Content

The new documentary "The Story of the Jews" explores the 3,000 year history of the Jewish people and their impact on civilization. In this post, guest blogger Jeremy Katz revisits a gruesome chapter of Jewish history in Georgia: the Leo Frank Case.

(All images are courtesy of the Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at The Breman Museum unless otherwise noted)

The most infamous case of anti-Semitism in America occurred in Atlanta. On August 17, 1915, Leo Frank was lynched in Marietta, Georgia. Two years earlier, Frank had been accused, indicted and convicted for the murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old girl found murdered in the basement of the National Pencil Company factory where Frank was the superintendent. After Georgia Governor John Slaton commuted the sentence from death by hanging to life in prison, a group of influential citizens in Atlanta executed a bold plan to abduct Frank from his jail cell and lynch him in Marietta close to Mary Phagan’s ancestral home.

A Jewish Yankee Comes to Atlanta

Leo Max Frank was raised in Brooklyn, New York and attended the Pratt Institute and later Cornell University where he studied mechanical engineering. He enjoyed leisure activities of the upper class such as tennis, chess and bridge and he was a frequent operagoer. He was also well traveled, particularly in Germany where he studied pencil manufacturing. When Frank arrived in Atlanta to work at the National Pencil Company, these activities, his industrialist background and his Yankee mannerisms made others, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, uncomfortable.

Frank met Lucille Selig shortly after arriving in Atlanta and married her despite their apparent differences, such as her disinterest in speaking Yiddish. He was known to be quite handsome and social, even in Atlanta, where he was a member of the Jewish fraternal organization, B’nai B’rith. He was well known, not because he was Jewish, but because he was one of the many Yankee industrialists who had moved to the South for profit. This made him quite unpopular in some southern circles.

The Murder of Mary Phagan

Saturday, April 26th, 1913, was Confederate Memorial Day. That morning, 13-year-old Mary Phagan took a streetcar from her home in Bellwood to the National Pencil Company factory to collect her pay before heading to the parade. She arrived at the factory around noon and proceeded to Leo Frank’s office on the second floor.

The following morning, her body was discovered by the night watchman in the basement of the factory. Police soon arrived on the scene and began their investigation. As the superintendent of the factory, Leo Frank was summoned by the police. After viewing the body, Frank admitted to seeing her the day before when she came to receive her pay. Frank was the last person to admit to seeing the young girl alive and consequently, with little additional evidence, was arrested for the crime.

The Trial and Appeals

On July 28th, 1913, the trial of Leo Frank began in a courtroom crowded with spectators. The prosecution’s main witness against Frank was Jim Conley, a black janitor at the factory also accused of the crime after he was seen washing what looked like blood out of a shirt. Further, Conley’s handwriting matched that of the murder notes found near the crime scene.

Conley testified on the witness stand that Frank killed Mary Phagan and recruited Conley to help him move the body to the basement. Conley also claimed that Frank dictated the murder notes to him in order to pin the crime on him. When Frank took the stand, he denounced Conley’s testimony as “a tissue of lies from first to last.” The jury accepted Conley’s word over Frank’s and he was sentenced to death by hanging.

Following the guilty verdict, Leo Frank’s attorneys submitted a motion for a new trial because they believed that public opinion had altered the outcome of the trial. There was no question that large crowds gathered outside the courthouse every day of the trial, but whether their jeers of “hang the Jew” could be heard from inside the courtroom was debated. The motion was first denied by the presiding judge who stated, “I am not certain of this man’s guilt…But I don’t have to be convinced. The jury was convinced.”

Soon after, the Georgia Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court denied the appeal for a new trial.

Commutation

Leo Frank’s last hope after being sentenced to death was Governor John Slaton. After carefully reviewing the thousands of pages of court documents, personally investigating the crime scene, and acknowledging new evidence such as Conley’s own lawyer asserting his client’s guilt, the governor decided to commute Frank’s sentence from death by hanging to life in prison.

In the middle of the night, he transferred Frank to the State Prison Farm in Milledgeville an hour outside of town for his safety. Once word broke about the governor’s decision, riotous crowds gathered outside of the capitol building and governor’s mansion and burned Governor Slaton in effigy as the “King of the Jews.” In Milledgeville, Frank was relieved to be spared from the gallows, but still determined to receive full vindication in the near future.

Lynching

Soon after Leo Frank was taken to the State Prison Farm in Milledgeville, a small group of leading citizens from Mary’s hometown of Marietta in Cobb County met to formulate a plan to deliver the justice they felt had been denied Mary Phagan and the State of Georgia.

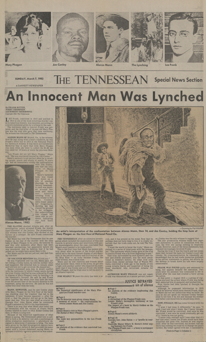

Members of the lynching party were all politically well connected, financially secure, and socially prominent. On August 17, 1915, these men put into motion a highly organized plan.

They stormed the state prison with guns at their sides, met no resistance from the prison staff, and drove Frank four hours to a large oak tree at Frey’s Gin, two miles from Marietta, where they lynched him early that morning. Within ninety minutes, a crowd of 1,000 onlookers had gathered to view the scene.

Aftermath

While articles covering the lynching of African Americans were relegated to the back pages, if reported at all, the lynching of Leo Frank made national news. Atlanta newspapers and those throughout Georgia condemned the lynching. The national press lamented Frank’s fate and denounced Georgia and the entire south as a region of illiteracy, bigotry, blatant self-righteousness, cruelty, and violence.

The lynching inspired the reorganization of the Ku Klux Klan, a hooded fraternity of horsemen that had disbanded in 1869, and whose midnight rides, cross-burnings, and ferocious attacks against African Americans had spread terror across the South.

The lynching of Leo Frank also served as a catalyst for the formation of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) of B’nai B’rith, which committed itself to fighting injustices and prejudices against the Jewish people.

Pardon

In 1982, the Frank case was back in the news with a startling revelation. Alonzo Mann, Frank’s former office boy, claimed he saw Jim Conley carrying the body of Mary Phagan into the lobby of the National Pencil Company. Mann, who was only fourteen at the time, said Conley threatened to kill him if he revealed what he saw. Terrified, Mann kept the secret for sixty-nine years. This new evidence encouraged members of Atlanta’s Jewish community to petition for a posthumous pardon for Frank. Attorneys at the Anti-Defamation League initiated the process which finally ended in a diluted victory in 1986. The Board of Pardons and Paroles did not address the question of guilt or innocence, but rather a pardon was issued based on the State’s failure to protect Frank from the hands of his assailants.