Section Branding

Header Content

The Chattahoochee dams in Columbus were removed 10 years ago. Has the river been restored?

Primary Content

The black cormorant spreads its wings wide, taking in the wind to dry its feathers on a breezy fall day. Perched on an outcrop of a boulder on the Chattahoochee River in front of the TSYS office, the bird is joined by another. They share the boulder.

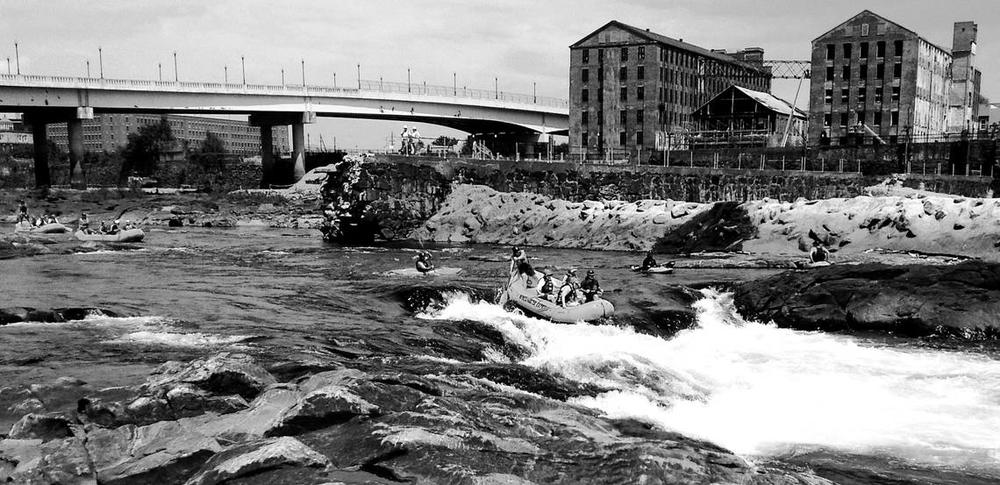

Boulders like these were covered by still, stagnant, and dirty water, unchanged for over a century, by two dams: the Eagle and Phenix and City Mills, until 2012 and 2013. These two dams would undergo “unprecedented dam removal operations” to revive and re-engineer the river creating a 2.5-mile urban whitewater course.

Many refer to this undertaking as the “river restoration project.”

A decade after this river transformation, is the river better off? Is the city better off? Is it restored? This two-part story will take a trip down the Chattahoochee to explore the economic gains and environmental challenges over the last decade that have incurred from the $26 million restoration project.

A brief history

Columbus and the Chattahoochee River are inextricably linked. It is the lifeline of the city.

“If it were not for these dams there would be no Columbus, Georgia,” Dean Wood archeologist of Southern Research Historic Preservation Consultants said.

The older and smaller City Mills dam, built in 1828, the year Columbus and this newspaper was founded, sat about a quarter of a mile (2000 feet) north of where the cormorants are basking in the sun. Between five and eight feet high and made of a stone foundation in a wooden frame, the dam powered a grist mill, grinding corn and feed for animals until the 1980s.

In 1868, after the Civil War destroyed parts of a massive textile mill, in the heart of downtown Columbus, it was rebuilt from its ashes and then named Eagle and Phenix. It wouldn’t be until two decades later in 1882 that a dam would stretch from Alabama to Georgia across the Chattahoochee to power the cotton textile mill adding a second small reservoir to the region.

The Eagle and Phenix dam was much larger than its predecessor at 30 feet high and 20-30 feet thick, Wood said. “It was the largest masonry dam in the south at the time. There was a need for more horsepower from the technology changes and demand increasing.”

It was made with giant boulders pitted together with concrete. “A monster, and an engineering marvel,” Wood said. It would continue to operate until the 1990s.

In 1972, the National Park Service listed the Columbus Industrial District, including the two masonry dams, as National Historical Landmarks.

Mill dams out, Waveshaper in

In 2003 W.C. Bradley, the legacy cotton manufacturing company that now works in real estate and selling home goods, purchased the Eagle and Phenix Dam. The safety and stability of the nearly two-century-old dam were not well understood, and W.C. Bradley was liable for any harm incurred.

Ideas to create an urban white water course on the river were floated around by the outdoor store owner, environmentalist, and naturalist Mr. Neal Wickham. Wickman and John Turner, son of the former CEO Bill Turner of W.C. Bradley, heard about engineering rivers to create urban white water courses from other success stories throughout the country.

Wickman and Turner thought: let’s not just remove these nonfunctioning impoundments but actually create waters that are more appealing to kayakers and rafters bringing in tourists and money to the city. This is highlighted in the Chattahoochee Unplugged documentary.

Uptown Columbus was on board and funded the project. Planning and feasibility efforts to remove the dams and transform the river for kayak and white water recreation would take place for two years.

Uptown Columbus, Turner, and others assembled an all-star project team: engineers, hydrologists, divers, historic preservationists, the Army Core of Engineers, environmental scientists, biologists, and professional kayaker and wave-making engineer Rick McLaughlin, to name a few.

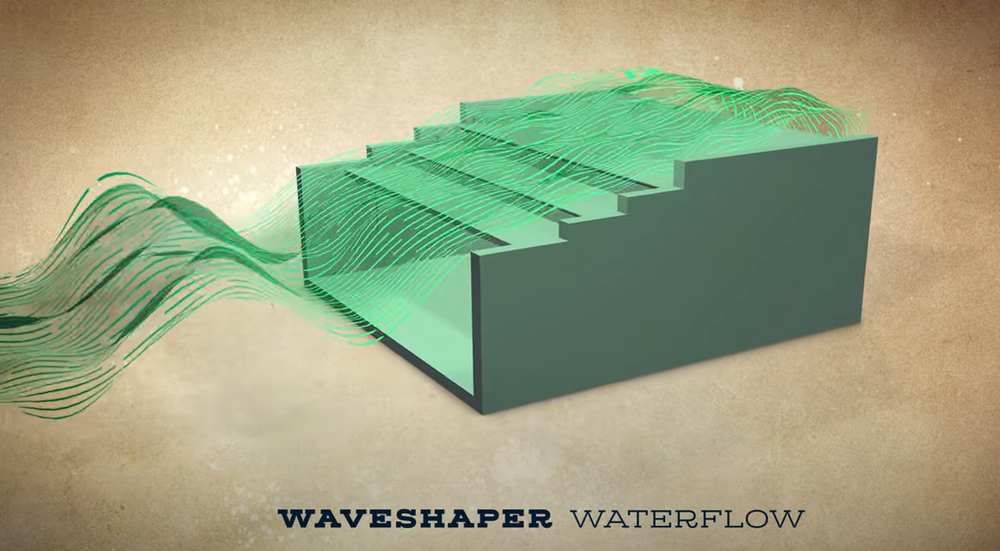

After many tests in labs, computer simulations, and underwater soil probing to understand the river’s potential, it was understood by McLaughlin that once these dams were removed, the river wouldn’t offer waves that were appealing to kayakers and rafters. Humans would have to build and shape the river to make waves.

A steel mechanical, 60-foot-wide structure with movable veins shaped like airplane wings dubbed “waveshaper” would do the trick. This fluctuation was key given the North Highlands dam 2.5 miles north will inevitably create low or high waters depending on demand.

When the time came to detonate the dams and install the wave shaper, Columbus’s leadership was all in.

“What we do here today is as critical to the history of Columbus as when the first stone was laid on the first mill of these shores,” Teresa Tomlinson, former Columbus Mayor said in September 2011. The first serious construction began and concrete steps were poured.

The section of the Chattahoochee River near Columbus went from two large, lifeless, reservoirs to a beeping construction site from 2011-2013. Bulldozers carrying steel would ride over where feet of water once stood idle for centuries.

During the end of 2011 and the beginning of 2012, a lot of moving parts had to happen simultaneously. Within the same few months of the City Mills dam detonation, several players worked together to preserve artifacts, divers scanned sonar maps in the water of the dam to record imagery. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers required mitigation and record-keeping before they were destroyed. Historic archeologists documented old artifacts that piled up behind the City Mills dam.

“The morning after the Eagle and Phenix was breached, we sent our teams to the river bottom to work carefully with engineers and Georgia Power,” Wood said.

The waveshaper was installed in November 2012.

During construction, Uptown Columbus vetted different whitewater companies. White Water Express, which operated out of Nantahala in North Carolina and Ocoee in Tennessee, was chosen as the outfitter.

“We worked with Richard Bishop (then Uptown Columbus president) on a daily basis in 2013,” Daniell Gilbert, son of the White Water Express owner, Dan Gilbert.

A blast occurred the morning of March 11, 2013, breaching an impoundment, and creating a different type of movement in the area for the first time in nearly two hundred years. White Water Express started doing test runs on May 25, 2013.

The river was now ready for thousands of long-awaited rafters and whitewater enthusiasts to experience the rapids. According to Gilbert, White Water Express brings in 45,000 people on the water annually, with a big spike of 50,000 in 2021 after some COVID restrictions were lifted.

Millions of dollars and millions of people

This project changed the character of downtown within just a few years. The following year, Blue Heron Adventure created a 1,200-foot-dual-zip-line connecting Alabama and Georgia, adding another river activity in Uptown Columbus.

Visitors to Columbus have reliably increased (minus a dip during the pandemic) since the restoration project finished in 2013. The biggest boom shows up in the increase in the amount of hotel rooms in Uptown.

“The majority of people come upwards of 3-4 hours to raft, and usually stay the night,” Daniell Gilbert said.

“These hotels started construction as early as 2017. Last year our economic activity of over $230 million in property investments including building renovations in Uptown broke our previous record,” he said.

The revenue brought in from this project has been enormous, especially considering the whole project including (a hydrologist, dam removals, inspectors, engineers, and real estate acquisition of the dams) came at a price of $26 million.

Since the restoration project, the Columbus section of the Chattahoochee River has hosted the 2017 and 2018 U.S. National Championships, the 2022 World Cup, and then the world championship in 2023. The world championship is “like the Olympics of kayaking”, according to Gilbert.

This is a far cry from the Columbus of ten or twenty years ago.

“Columbus is night and day compared to when I first got here [in 2013],” Daniell Gilbert said.

Locals and visitors interact with the river through kayaking, rafting, fishing, and using the riverwalk to bike, walk, or run. There is a pulse, that ripples from the surface of the waves to the streets of Broadway. It is quantifiable and measurable.

Health with limited data

Measuring the health of the river below the surface of the water is much less straightforward than counting visitors, hotels, or revenue. It requires sampling for fish populations, planting shoal lilies, counting invertebrates and birds, and testing water quality.

There are efforts by Chattahoochee River Conservancy to plant Shoal Lilies, a native plant that creates habitat for fish. The Chattahoochee Riverkeeper and the River Conservancy both measure water quality.

However, due to limited resources for the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), there is no consistent data on fish populations in this area.

“Fish are a very good indicator of ecosystem quality,” Brett Hess, Fishery expert of Georgia DNR said. The DNR lacks the manpower and financial resources to consistently test for fish population, specifically in the Columbus region of the Chattahoochee. They rely on universities and anglers, Hess said.

Senior research fellow and Fishery scientist, Steve Sammons at Auburn University is the expert when it comes to fish in the Columbus area. His passion and focus lies with Shoal Bass, an endemic black bass species.

It is a rare, sensitive, and native to the Chattahoochee. Since he started this focus in 2007, their numbers have dwindled. But this is only from the few samples that Sammons has done.

“The future of the species is at risk in the Chattahoochee,” Sammons said.

Hess went as far as to say “Shoal bass are the bald eagle of [the restoration project]”.

In 2014 and 2015 Georgia Power sampled the area for fish and didn’t find much, according to Sammons.

“Oddly enough when the dams came out, the shoal bass disappeared,” Sammons told the L-E. “I was surprised by the results in 2014 and 2015, but you have to remember we didn’t just remove dams we built a white water course. You have to wonder, by putting the course in, did we create our own barrier?”

In 2017, Uptown Columbus and the Army Corp of Engineers did a post-dam removal sampling. “Things still didn’t look different,” Sammons said. This was the only “required” sample.

Next week on November 29, Sammons will go out and electrofish (zap the water to quickly stun the fish and get a count) to get the first sample collected since 2017.

Part II will explore the latest information on water quality, the effect dams have on fish (and shoal bass), Steve Sammons’s latest numbers, and what a changing climate means for the river.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with the Ledger-Enquirer.