Section Branding

Header Content

Don't look so blue, Neptune: Now astronomers know this planet's true color

Primary Content

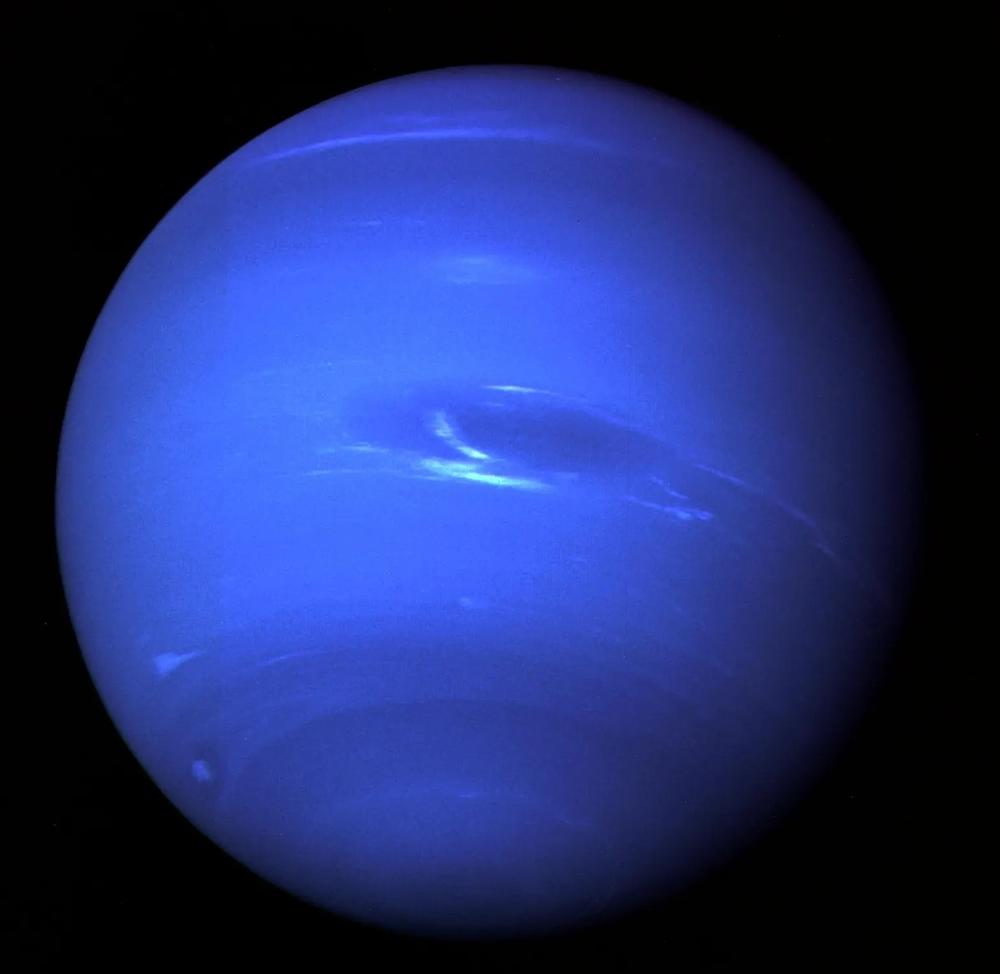

In 1989, Voyager 2 became the first and only spacecraft to ever fly by Neptune, and images from that mission famously show a planet that's a deep azure color.

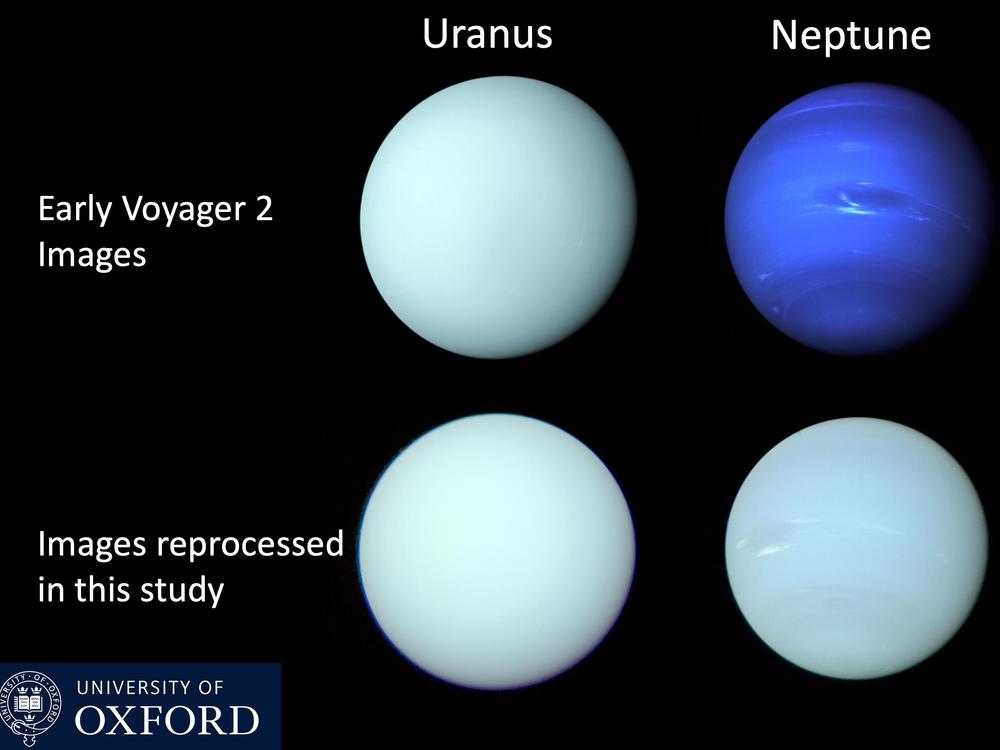

But in reality, Neptune is far more of a light greenish blue. It's actually pretty similar in color to its fellow ice giant Uranus, also visited by Voyager 2.

"We find that the planets are different colors, but the difference in color was nothing like what you see when you Google for images of Uranus and Neptune," says Patrick Irwin, a planetary physicist at the University of Oxford.

Irwin led a team that did a new analysis that's just been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The researchers rebalanced composite color images taken by the Voyager 2 camera, using data from instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope as well as the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope.

The resulting images more accurately reflect the true colors of these planets, says Irwin, as they'd be seen by the naked eye.

As a result, some of the key features of Neptune, such as cloud bands and a dark spot, become "indistinct and difficult to see," he says, noting that the Voyager team deliberately processed its images in a way that would highlight the unusual features of this planet.

"This is a very common thing to do. You're effectively trying to tell a story and to point out to your audience what the interesting features of those images might be," says Leigh Fletcher, an astronomer with the University of Leicester. "But even amateur astronomers looking through their own backyard telescopes up at Uranus and Neptune knew that the contrast in colors between those two worlds was rather more subtle than maybe the original NASA's images first let on."

Although Voyager scientists were open about how they processed their images, says Irwin, the subtleties of those decisions have gotten lost over the decades as the images of Neptune and Uranus have been endlessly reproduced.

"People now just think, 'Well, that's how they look,'" Irwin says, adding that when people see his team's new vision of Neptune, they're "quite surprised."

In addition to rebalancing Neptune's colors, the research team also investigated the unusual color changes seen on Uranus during its 84-year orbit of the sun.

Using observations taken from 1950 to 2016 by the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, they found that Uranus appears a little greener at its solstices, when one of the planet's poles is pointed toward the sun.

But when the sun is over the equator, Uranus looks a bit bluer.

The researchers attribute this color change to the fact that the poles have less methane than the equator, plus they have an increased amount of icy haze.

"We now have a model capable of explaining why those subtle colors are changing," says Fletcher, who notes that it took decades of data and calculations that can replicate how light interacts with various gases and aerosols.

In a description of the new research released by the Royal Astronomical Society, Heidi Hammel, of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), is quoted as saying that astronomers have been bedeviled for decades by the misperceptions of Neptune's color, as well as the color changes of Uranus.

"This comprehensive study," Hammel said, "should finally put both issues to rest."

Some astronomers have long lobbied for a new mission out to one of the ice giant planets, and an influential priority-setting panel for astronomy recently put a robotic mission to orbit Uranus at the top of its wish list.

"We're talking about launch dates in the 2030s and not arriving until 10 years later," says Irwin. "So it's to be beyond my professional career, but hopefully not my life."

Fletcher says no one really knows what the insides of these ice giants are like, and there's certain regions of these planets and their moons that no human or robotic eyes have ever seen.

"Going out to these destinations will be revealing environments, revealing landscapes, revealing atmospheres that nobody's ever seen before," he says, adding that it's one of the few places left in the solar system with the potential to make such discoveries.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.