Section Branding

Header Content

Teens can't get off their phones. Here's what some schools are doing about it

Primary Content

Last October, Claire Pauley and her husband Mitchell Rutherford learned they were expecting their first child. However, Rutherford kept forgetting about his wife's pregnancy. There was something else on his mind.

"I mean, when I went to school, I would forget that we were pregnant and I would come home and I wouldn't remember until my wife would say something about it," Rutherford said. "I'd come home and just collapse on the floor. I was suicidal at times."

He was a high school biology teacher in Tucson, Ariz. and his students' near-constant smartphone use was taking a toll on his well-being. So when summer rolled around after his eleventh year in the classroom — he quit.

"I came to realize that the phone addiction that the students were struggling with was causing severe mental health problems for me, preventing me from being a good husband," Rutherford said.

Some states are trying to legislate against pervasive phone use in schools. Florida, South Carolina and Louisiana have statewide restrictions — and states like California, Indiana, Minnesota, Ohio and Virginia have policies requiring districts or schools to create policies banning phones, according to findings from EducationWeek.

During the 2023-2024 academic year, Rutherford says his students were significantly more disengaged. He felt like he wasn't making a difference.

"Most of the people in the class, they've got their headphones in, they've got their phones on. They're not actually listening," Rutherford said.

He says that as a teacher with ADHD, he fed off the energy of his class.

"I'm really aware of whether someone's listening to me or paying attention to me." Rutherford said. "And this year," he told NPR at the end of the 2023-2024 school year, "I was just like, 'I can't…They're not interested in what I have to say.' And that, frankly, is the reason that I had to leave."

In addition to the phone use, students were not interacting with each other, sometimes writing in journal entries that they were anxious, depressed and lonely — which made them burrow further into their devices, Rutherford said.

Finding focus again

Teachers NPR spoke to about phone use in class say students' inattention and social isolation was made worse during the pandemic.

"It just got to be really exhausting to deal with phones on a case-by-case situation," high school English teacher Emily Brisse said. "Nobody goes into education in order to become the phone police. We want to be able to focus on our content."

Her school in Golden Valley, Minn., was among those that implemented a phone ban in recent years.

Right after it went into effect, she noticed students were more engaged and some admitted in feedback forms they appreciated it.

"[It] forced them to kind of learn how to socialize again, how to be entertained by each other, how to turn toward the learning, even in moments of silence, even in moments of boredom," Brisse said.

It's not a bell-to-bell policy — but Brisse is OK with that. Although they are on their phones during passing periods, she said "there's plenty of chatter in the hallways" as well.

Some schools are taking it a step further — by prohibiting students from accessing devices throughout the entire day, not just during class time.

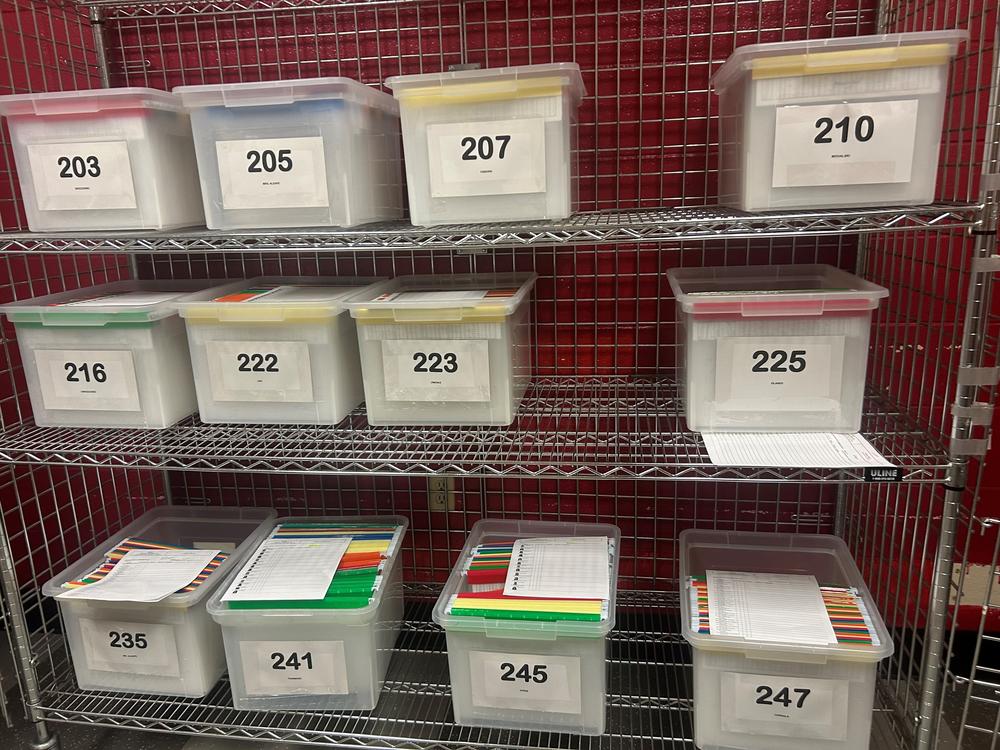

Once a week, English teacher Abbey Osborn heads to work 10 minutes early for phone-collection duty at her Milwaukee, Wis. high school. Since 2018, her school has collected students' phones every morning as they come into the building. The phones are returned during the last hour of the day.

"The students are focused. There's still definitely lots of chatting, lots of relationship building," Osborn said. "I've also found that students are more willing to work together in groups when they don't have their cell phones."

At the end of the day when the cell phone bin is delivered to class, Osborn says students crowd around it "like vultures."

Once the phones are passed back to students, she says they immediately look at them. In her view, that shows that "they don't have the self-control to be able to handle the demands of school and access to a cell phone."

They benefit from not having to think about their phones the entire day.

On the basis of age alone, teens already struggle more than adults with controlling their impulses: the brain's prefrontal cortex, which is involved in impulse control, is one of the latest brain regions to fully mature — and continues to develop into adulthood, according to a 2021 publication in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology.

Human brains are also wired for social connection — something that's often top priority for adolescents — and a lot of it now happens online.

"As an adolescent, you are super primed to social belonging, social validation, status. Also the brain is not fully developed," said Zach Rausch, lead researcher for social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, whose 2024 book, The Anxious Generation, details the harms of near-constant smartphone usage on young people's wellbeing.

"So when you combine those things together and you have social media platforms that are all about social validation — it's hard to stop to regulate yourself," he says, adding that it's why teens spend so much time on their phones.

Learning these skills is made even more difficult when facing a near-constant barrage of notifications. A 2023 report from Common Sense Media found that teens received a median of 237 notifications per day.

Getting phones out of schools

Julie Scelfo founded the advocacy group Mothers Against Media Addiction after reporting on rising suicide rates among children, who are increasingly spending more of their lives online.

Scelfo feels that smartphones have taken the place of in-person experiences that are necessary to build healthy social and emotional health, as well as academic success.

"I thought I could give my kids these products and teach them how to use them safely," Scelfo said. "But there is no 'safe' when they're designed to be addictive," she said — noting that "the more time they spend on these platforms, the more money these social media companies make."

When her three sons first got smartphones, she used parental controls to prevent them from seeing "harmful content," but regrets not waiting longer to give them smartphones in the first place.

"We don't take our kids to casinos and say, 'OK, you can gamble a little, but you should leave.' We don't give our kids alcohol to drink or drugs. We recognize that these products are designed in such a way that they're really hard to use safely, and it's more appropriate for adults to do that, not children," Scelfo said.

Many schools are also turning to lockable pouches to keep students off devices.

A decade ago, Graham Dugoni founded Yondr, which makes and sells locking phone pouches to schools that students carry with them. At the end of day, they tap the pouches on a magnet that unlocks them.

"A lot of the districts and schools that come to us have tried different methods and they end up coming to us because those haven't worked for one reason or another," Dugoni said.

When phones are stored in cubbies in classrooms, students still check them in passing periods, he said.

Today, Dugoni says more than 2 million students use pouches in America. He says in schools that use Yondr pouches — more library books are checked out, there's more socialization and clubs are being revitalized, according to Yondr.

Phone bans aren't a one-size-fits-all

Despite the seeming benefits of phone bans, schools don't always have the resources to enforce them. Some students care for siblings after school and need to coordinate with parents. Students whose first language is not English can benefit from using a translation app during class.

If society continues to depend on smartphones, students will eventually need to learn how to have a phone without constantly checking social media.

Megan Grady teaches eighth grade in Sterling, Ill. and she doesn't think phones should be banned in the classroom so that her students can learn discipline.

If she sees a phone, she'll take it and give it back at the end of class. For repeat offenders, she'll take the phone to the office for a parent or guardian to pick up at the end of the day.

"They need to learn a little bit more self-control," Grady said. "I think learning from a young age that there's a time and place to use our technology, I think would benefit them in the long run."

Correction:

An earlier version of this story misspelled Abbey Osborn's last name as Osborne. It has been updated with the correct spelling.