Section Branding

Header Content

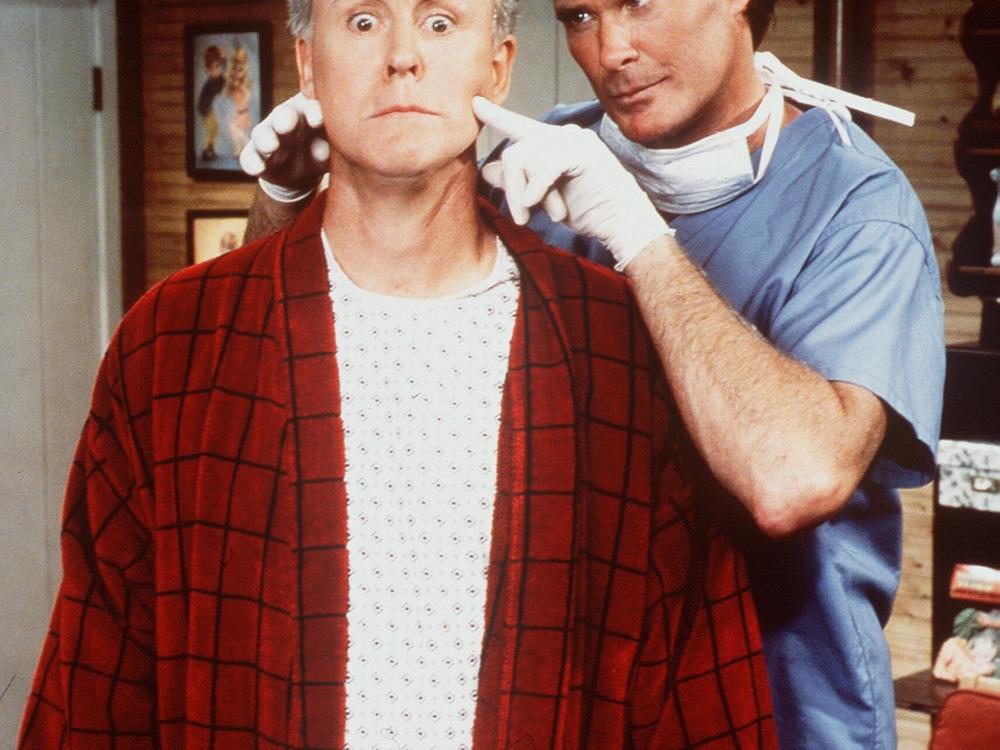

John Lithgow on having a "good ending" — on and off screen

Primary Content

A note from Wild Card host Rachel Martin: Who is your John Lithgow? We had a staff meeting recently where we all went around and named the character who made us love John Lithgow and the choices were as varied as his career.

Mine is Reverend Shaw Moore, the pastor from the movie Footloose, who banned dancing in his small Texas town and, in doing so, gave Kevin Bacon one of the best "I'm-so-mad-I-need-to-do-gymnastics!" scenes of all time.

Our producer said her John Lithgow is from the 1983 Twilight Zone movie. Our editor said his Lithgow has to be Dick Solomon, the patriarch of the alien family in the massively popular TV show 3rd Rock from the Sun.

John Lithgow seems to have done all the things: theatre, movies, TV. Good guys, bad guys… lots of bad guys. Or just maybe complicated characters, including Winston Churchill in The Crown and a very small king in Shrek. This is an actor who is willing to take a risk, play against type, and elevate the profound and the ridiculous.

And it must be said the man loves to work. Just in the last few years, he's been in the Hulu series, The Old Man, a play about the writer Roald Dahl, the movie Conclave that came out earlier this year, as well as the new animated film Spellbound.

This Wild Card interview has been edited for length and clarity. Host Rachel Martin asks guests randomly-selected questions from a deck of cards. Tap play above to listen to the full podcast, or read an excerpt below.

Question 1: What was a moment in your life when you could have chosen a different path?

John Lithgow: Oh, my entire childhood I had chosen a different path. I grew up in a theater family but did not want to be an actor. I didn't even consider it because right up until I was about 17 years old, I fully intended to be a painter. I was quite committed to it [for] as long as I can remember. You know, if I were ever asked any version of what you want to be when you grow up — it was always an artist. And I had great encouragement from my parents.

Rachel Martin: So, they were not steering you in the direction of the theater?

Lithgow: Not at all. They weren't discouraging me. Although I do remember when I told my dad that I was auditioning for a Fulbright to study acting in earnest in London, his face fell, like, "Oh, my God, no." And I said, "Dad, you've produced all these Shakespeare festivals, you've even hired me to act. What did you expect me to want to do?" And he said, "Well, I always thought that it would be a good idea for you to go to business school." And I said "What?"

Martin: Oh, interesting. So it's not like he held up your artistic dreams. He wasn't like, "Oh, I really thought you were going to be a painter…"

Lithgow: Yeah. And I said, "What are you thinking? I would never go to business school." He said, "Well, as a theater manager, I've always felt that my great failing was in the area of business."

Martin: I mean, we all as parents do that to some degree, I imagine, even though I try not to, my kids are sort of young, but, you know, project your own, "I've learned the hard way. You know, the theater is tough!" So, you know, he struggled in the trenches and maybe he wanted something different for you.

Lithgow: He struggled terribly. It was a very tough life for him. And I think he just felt the need to spare me.

Martin: Right. And I bet your dad was proud of you in the end.

Lithgow: Oh, ultimately, yes, of course. It's worked out just fine.

Question 2: What period of your life do you often daydream about?

Lithgow: I think it's my early years in New York theater – the 1970s. I would say in any given year, in the 1970s in New York, I probably was acting on stage or on Broadway on about 300 of the 365 nights. I mean, I just went from one theater job to another.

Martin: It sounds exhausting…

Lithgow: Oh it was just – I was young! I got everywhere on a bicycle. I acted. God, I did a show in 1975 at Lincoln Center, Trelawny of the "Wells." Among the cast were Mary Beth Hurt, Sasha von Scherler, and Mandy Patinkin in his first role – and, in her first job out of Yale Drama School, Meryl Streep. We were all thick as thieves and we would have big potluck suppers together.

Martin: That's worthy of daydreaming, yeah. Things felt limitless for you then?

Lithgow: Yeah. Even though it was really tough and the town was dirty and dangerous and depressing in every way — except if you were a young actor, it was just electric.

Martin: Does that in any way mean that theater is still where you feel most at home?

Lithgow: In a sense. I mean I like everything I do as long as I'm employed. But the theater is where you feel like you're using absolutely everything you've got and you're in charge of the story.

Question 3: Do you think there's more to reality than we can see or touch?

Lithgow: I have a pretty simple version of reality. You're immediately making me look around me like what's real and what isn't. And everything I see is real.

I think of death as death. I don't think there's life after death or a soul after death. I had an extraordinary death experience, two years ago. I directed that wonderful New Yorker, Doug McGrath, in his one-man show that he had written for himself. He had a wonderful little off-Broadway success with it and it was in his third week of a run. He was going to do it as long as he wanted in a tiny theater downtown. And he didn't show up at the theater one night because in his office, by himself, at about four in the afternoon, he'd lain down, had a heart attack, and died — at age 64.

And it was such a traumatic thing to experience. He died painlessly and almost courteously. He didn't make anybody else suffer over his death except over the fact that it had happened like that [snaps].

Martin: And did that change anything for you and how you think of it? The end-ness of it all?

Lithgow: I was startled at how soon I was able to absorb it as just having happened and the new reality. This lovely man who was quite a dear friend, having worked together so closely, he was simply gone. And I knew that he was gone. And the brain simply adjusts.

Martin: Did it make you any more or less comfortable with your own demise?

Lithgow: More. I just know it's coming. And I think the best thing is to have a gracious ending. You know, I calculate my exit from any film or television or stage play, and I always want to have a good ending. Well, I want to have a good ending to my life too. That no one grieves over.

Martin: Well, people will grieve.

Lithgow: I can't believe I'm talking about these things. I've had three cancers in my life. First in 1988, 2004, and then only a couple of years ago — in every case dealt with immediately and put an end to, you know. Melanomas that could be detected early and removed. A prostatectomy that eliminated prostate cancer from my life. But I'm almost glad that I had the shocking experience of being told, "You have a malignancy." To have realistically contemplated, "Oh my God – this might really, I might die of this." I think it was a useful experience to have in terms of just putting your whole life into perspective.