Section Branding

Header Content

How language barriers among older adults increase risks in health care system

Primary Content

LISTEN: Language barriers are putting older adults at risk in the health care system. Without an advocate, Georgians who cannot speak or understand English well are more likely to suffer abuse and neglect. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge has more.

Luz Ospina spent 38 days in a long-term acute care facility last year. She was only supposed to be there long enough to wean off a ventilator after an Atlanta hospital discharged her.

The 73-year-old was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease, after a trip to the emergency room a few days after Christmas 2023.

"That led to respiratory failure," said Ospina’s daughter, Linda Perez. "That's why she was on a ventilator."

Her mother wasn’t improving in the long-term care facility, and she couldn’t explain why because of a language barrier.

"Me sentí bastante abandonar," Ospina said. "I felt abandoned," Perez translated.

Despite laws requiring trained interpreters, doctors there spoke only in English.

"There was one person maybe that made a small effort to try to communicate with her, but the norm was no communication in Spanish," Perez says.

Ospina was left with little more than body language, and her mental health declined.

Every few days, a psychiatrist stopped by and asked Ospina the same questions.

Was she depressed?

"Y siempre me decía, 'ustedes deprimida?' ... yes, I am," Ospina said.

That much she could confirm in English, but deeper communication in Spanish wasn’t possible.

Perez insisted the facility provide interpretation services, "and they brought a phone with a cable that was so short that you couldn't even get the phone close to the patient."

Then, Ospina’s chart didn’t match what Perez was seeing.

"When I read the reports it's like, 'Patient is fine. She's fine. She's fine.' and he didn't even use the translation line," she said.

Then, her mother was prescribed anti-anxiety medication.

"You should ask a neurologist what happens to a patient with myasthenia gravis that receives Xanax twice a day," Perez said. "She could have died."

Perez said there should be an alarm every time a drug is prescribed that patients shouldn't take.

"There should be safeguards," she said. "It's a safety concern."

- RELATED: 1 in 4 nursing homes use 'chemical straitjackets' to manage residents, US News & World Report says

Almost 1.5 million Georgia residents speak a language other than English at home, according to Census data, and under Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act, health care facilities must provide interpretation services.

Plus, studies show that older adults with language barriers are at increased risk of hospital readmission.

Sung Yeon Choimorrow is with the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF).

She said translation services aren't as common as they should be, and while it’s tough enough to find Spanish translation services, her parents speak Korean.

"My dad ended up having needing emergency brain surgery, and that whole experience was so traumatic for [my parents] that they decided to move back," she said. "They did not want to deal with the medical system here."

More than 100 different languages are spoken within the United States by descendants from the Asian continent.

Choimorrow said language barriers mean more stress on family caregivers.

"Even if my dad can understand most of what the doctor says, he still wants me there because he wants to be sure," she said.

The Georgia Department of Community Health regulates long-term acute care facilities in the state.

Anyone can file a complaint with DCH online.

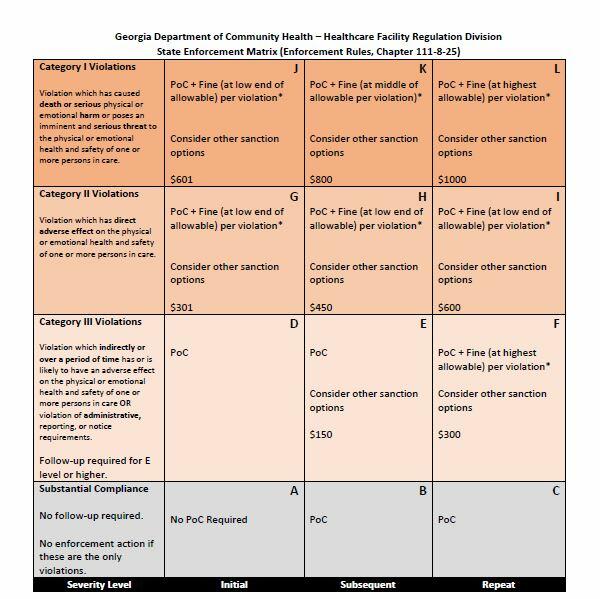

If a lack of interpretation services leads to death or serious injury the health care facility could be subject to a fine of up to $1,000.

Perez filed complaints with the facility about “multiple instances of neglect, mistreatment, unprofessional behavior from consulting physicians and violation of a patient’s right to receive interpretation services,” to which they responded in an email that staff had been re-educated about the policies and procedures regarding the use of translation services.

The response also acknowledged Perez's complaint about the Xanax prescription, saying they “identified a delay in acknowledging the alert in the medication administration record. The Director of Pharmacy has provided the feedback to those directly involved in your mother’s care.”

Perez fought to get another neurologist to send her mother back to the hospital after weeks went by and Ospina wasn’t getting better.

"She couldn't wean off the vent because her condition was not being treated properly," Perez said. "That was the job of the neurologist."

Perez says the staff neurologist would come in, look at and touch Ospina's feet, then write something down and leave without speaking to Ospina.

He kept saying it was a lung problem and that Perez needed to speak to the pulmonologist, who referred Perez back to neurology.

When she finally got a second opinion from a neurologist via telehealth, Perez explained that her mother’s myasthenia gravis was not improving as expected.

"Her eyes are droopy. She can barely lift her head," Perez said. "And she's not weaning off the vent because her muscles are not strong enough."

When the muscles needed for breathing are affected, a patient is said to be in myasthenic crisis, which MG Georgia national support group leader Alexis Rodriguez said is a life-threatening situation.

Around 15% to 20% of people with myasthenia gravis have at least one myasthenic crisis, which can be caused by an infection, stress, surgery, or a reaction to medication.

The first thing the neurologist said was that he couldn't do a proper evaluation on a patient with a ventilator virtually.

"He asked me if I knew that my mom was not a prisoner at this hospital and that opened my eyes because it really felt like she was a prisoner," Perez says.

"Me sentí muchisima mejor," Ospina said; she felt better immediately after arriving back in the hospital.

Perez believes her advocacy saved her mother’s life, "but there's so many people that don't have advocates."

It’s a year later and Ospina no longer needs to steady herself with a walker; she gets around just fine.

Perez is happy her mom is OK, but she won’t forget the families still struggling in silence.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations and The Commonwealth Fund.