Section Branding

Header Content

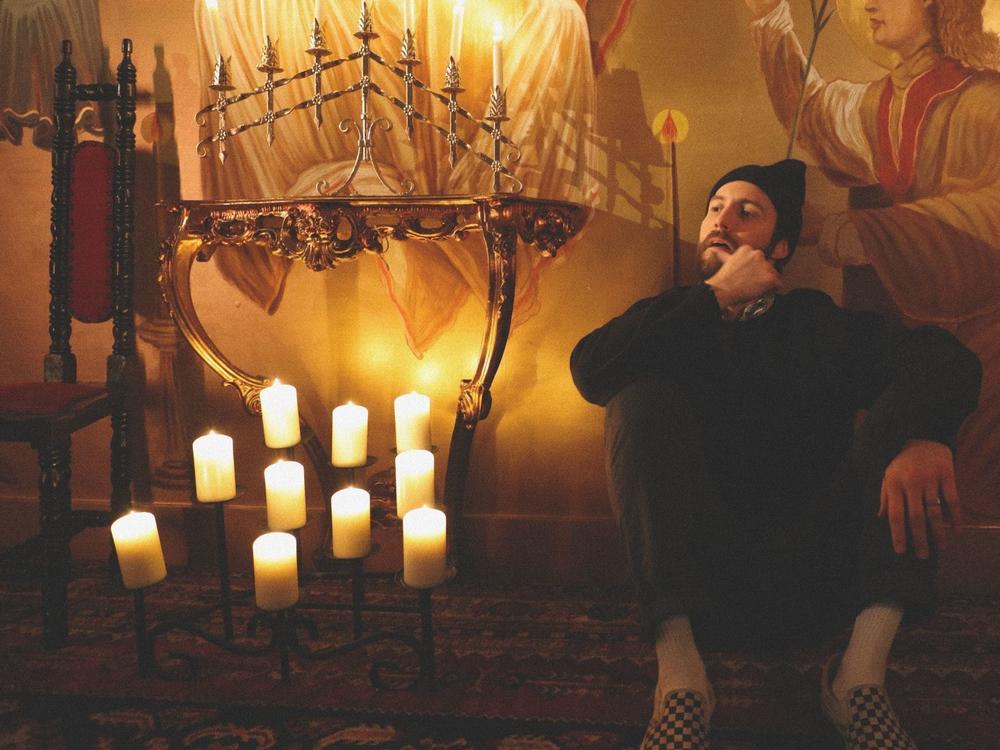

Listen To 'Teenage Dirtbag' With Me: Ruston Kelly On The Loser Anthem

Primary Content

A sensitive college dramedy in the age of the teen sex romp, Amy Heckerling's Loser hit theaters in July 2000 with a thud. It failed to earn back its $20 million budget, and by the time stars Jason Biggs and Mena Suvari reunited in American Pie 2 a year later it was as good as forgotten. The film's legacy might have ended there if not for one thing: Tucked into its run-of-the-mill alternarock soundtrack was a song by an unknown New York band, whose self-titled debut wouldn't even be out for another month. The track didn't sound like anything on the radio — rather, it sounded like everything on the radio.

For the first few bars of "Teenage Dirtbag," it's not clear what you're hearing is of any kin to rock music, as what sounds a busted cassette deck competes with what sounds like an MPC stuck in a washing machine. When a guitar finally arrives, it shuffles in smelling like hemp oil, treading an acoustic groove closer to Ani DiFranco or Dave Matthews than the missile attacks being conjured that year by Rage Against the Machine and Limp Bizkit. The percussion is lite hip-hop pastiche, its DJ scratches and ghost notes rendered swagger-free by the tonnng of an overcranked snare. And later, when that coffee-shop guitar finally tastes the might of an overdrive pedal, the result is basically a hair ballad but for the skronky stoner riffs between each line. None of this should work, but somehow the collision of sounds from across the FM dial finds a strange equilibrium, and you might even be bobbing your head by the time the vocals enter and confuse things all over again.

In interviews, Wheatus singer and songwriter Brendan B. Brown has explained that his high, puckered vocal presence was conceived years before the band existed, as a defense mechanism. "I would get beat up by older kids, and there'd be a lot of homophobic slurs," he told Rolling Stone of his adolescence in Northport, N.Y., where a much-publicized ritual murder in 1984 had made it extra-hard to be a metalhead loner. "I found that it'd compress the time that you're actually having the s*** kicked out of you if you antagonized them by donning a girl voice." It's a choice that suits the song's dramatic narrative, one you'll recognize if you've seen a single movie about high school. The narrator is head over heels for his classmate Noelle, a stunner in Keds who (we're told) deserves better than her meathead boyfriend. Alas, as an unpopular nerd well outside the in-crowd, our hero pines away in secret until one night changes everything. It sounds so simple, and yet in execution every moment is specific, weird, and memorable. Brown sets the story in a kind of cracked teen poetry, which takes as a given that "Man, I feel like mold" is a normal way to say you're sad. There are zoo-crew sound effects in the vein of early Eminem, a brass chime cued to the line "She rings my bell." And there is the over-the-top fantasy of the climax, where Brown switches into character as Noelle, surprising the hero with a pair of Iron Maiden tickets and confessing, "I'm just a teenage dirtbag, baby, like you."

Though it didn't crack the Hot 100, "Teenage Dirtbag" found a quiet staying power: It was an unlikely chart hit in the U.K. and Australia, its kitsch charm attracted movie and TV placements, its triumphant dynamics made it a karaoke secret weapon — and, in the past few years, a growing number of contemporary artists have adopted it as a new standard. SZA and One Direction have tackled it on arena stages, delivering note-perfect tributes with a little pop sheen. Phoebe Bridgers and Mary Lambert, two queer women with no need to upset the pronouns, have stripped it to an earnest ballad. But if there's one to rule them all as the most heartfelt and effective, it's a bourbon-soaked take out of Music City.

When I reached Ruston Kelly by phone at his home in Nashville, hours before his 32nd birthday, he was weighing whether he could add any more caffeine to his afternoon without regretting it. "I'm an ex-speed user," he volunteered, "so coffee is my guilty pleasure. Is four cups what I can do today?" On his sparkling 2018 debut, Dying Star, the singer-songwriter is no less frank, coiling his own journeys through chemical dependency and heartache around knockout couplets ("I get so f***** up I forget who you are / I dumb down my head so I can't feel my heart," goes the gliding hook on "Blackout"). His second album, Shape & Destroy, is due Aug. 28 — but late last year, the fans waiting for it got a surprise. Dirt Emo Vol. 1, a roughshod covers record, is both tribute and provocation to that nebulous punk subculture, applying rootsy arrangements to some songs firmly in emo's wheelhouse and others that tug at its boundaries: Taylor Swift rubs shoulders with My Chemical Romance, the Carter Family with Blink-182.

"Teenage Dirtbag" is the guest of honor, appearing twice on Dirt Emo — once as a quiet solo meditation, and again as a country-pop panorama as splendidly realized as any of Kelly's own best work, with revoiced chords, a slowed tempo, soaring pedal steel and the artist's gruff tenor selling the hell out of it all. In the era of meme culture, adding gravitas to pop hits is usually the domain of viral pranksters, but Kelly manages to evoke the song's core sentiment with a startling sincerity. Listen closely to the band version, recorded live onstage, and you'll hear the crowd singing along not in drunken ardor, but gently, like a church choir.

Ahead of the release of Shape & Destroy, as well as the 20th anniversary of Wheatus (which a still-active Brown and his bandmates will mark this year with their own song-for-song remake), I asked Ruston Kelly to tell the story of his own relationship with "Teenage Dirtbag," in the hopes of unpacking what has made the song so enduring, adaptable and uncannily relatable.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Daoud Tyler-Ameen: You were born in 1988, which makes you around 12 when "Teenage Dirtbag" came out. What was your life like when you first heard it?

Ruston Kelly: I was a competitive figure skater. I'd started when I was around 9: My sister was watching Stars on Ice, and I was like, "That's cool. I want to do that." We were living in Alabama then, not many ice rinks. But when we moved to Cincinnati, I just put on some skates, and it was pretty weirdly natural. My world consisted of disciplining myself athletically to win competitions, and then school was like a side project.

Since we moved around a lot, it was hard for me to make friends. And being a male figure skater, with some of these more jock-based clique structures I was exposed to, it was kind of difficult to fit in anywhere. When I was at school, I had the mentality of, "All right, just get through this." And so that song, I mean ... anthemic is an understatement. It just makes you feel empowered: "Oh, OK. There's lot of people that feel this way."

What is a teenage dirtbag? The song doesn't really explain it, but the phrase clearly struck a chord with you.

I mean, if someone calls you a name, and then you call yourself that, you automatically have power over what that name would try to take away from you. "Maybe I am just a confused, horny teenage piece of s*** sometimes, and that's OK."

Do you have a favorite line?

"Listen to Iron Maiden, baby, with me" — that's my favorite one. But I also like when they break it down and it's as if the girl is talking to him. I mean, what kid isn't fantasizing about their crush coming up to them and saying, "Hey, you know that band that you like that everyone makes fun of you for? Yeah, I like them too. Here's two tickets to their show tonight. Let's go."

Though you chose not to include that part in your version. How come?

This is one thing I like to do with covers: If you really make a cover your own in that moment that you're recording it, performing it, it's yours. You could do whatever you want with it. In my version, there's a bit of a heavier side, and I felt like [singing that part] was going to drag the sentiment through the mud a little bit. I didn't want to overdo it, you know? You've gotta watch out for that.

There are a ton of covers of "Teenage Dirtbag," and I will be honest and say that yours is one of the few that really works for me. I think it's because this song is very silly and also very sincere, and the trick to interpreting it is understanding that balance — because otherwise you're either too serious or you're making fun of it. Can you tell me what it feels like to perform it now, the way you do?

Well, there's two ways to do it. When we do it live with the full band, it's more in the spirit of the original. You're kind of in charge of the narrative about you being a dirtbag. When you do it stripped down, like the acoustic version, it's more from the angle of, "Aw, s***. I'm a lonely dirtbag." Both of those perspectives feed the essence of what that song is to me. It has this sentiment of, "Man, I'm so lonely," and, "This cheerleader's not gonna want to go out with me." And also, at the same time it's like, "You know what? I am this. So what?"

It's interesting to me that that sentiment hasn't curdled more over time. The song is kind of a movie in itself, in the spirit of the teen rom-coms that were super-popular then. They usually centered on a boy with a crush on a girl, who lives completely inside his head and can't stop asking, "Why doesn't she like me?"

Absolutely, always.

Some of those stories feel different now — a little creepy or cringey. The ones that do hold up, I think, are just very earnest and honest about what it's like to be young. I wonder what it is about "Teenage Dirtbag" that's allowed it to sort of stay pure.

It's the same reason why any song that has a timeless quality to it remains timeless: It's authentic. That's what makes for something lasting, whether that's a pop song, rock song, metal song, a comedy routine or an essay. If you mean it when you say it, it'll live on through that sentiment in other people.

To me, that's kind of what folk songs are. It's easy to think of folk songs as though you have to be playing, like, a clawhammer banjo or a weird tenor parlor guitar. But folk music is just everybody. It's the music you'd want to hum while you're gardening, or that you would fall in love with someone to while you're roller skating. It's just ubiquitous.

Let's talk about genre, since you mention it. You've explained that the idea of "dirt emo" comes from the two sides of your childhood: You grew up kind of a Warped Tour kid in a very Americana household. I don't know if you experienced this, but for a lot of my youth I remember people vigorously policing the boundaries of emo and punk, being very adamant about what did and did not belong. The tracklist of Dirt Emo Vol. 1 feels like a rejection of all that.

I think genre has a broader attitude about it now. Maybe you can't call George Jones country in the same sense as Kane Brown or something like that — but the thing is, Kane Brown is country. Pop country is country. Some people are like, "Well, that's not the way that Hank did it." Well, yeah, that was like 60 years ago. I don't really agree with any of that. I just think it's more, what's your attitude? If you're an artist and you have an attitude of, "All right, I'm going to call myself emo," it's pretty self-explanatory. And if you're into it, you are.

As a teenager I remember having a lot of borrowed nostalgia for '80s culture and '80s pop music, even though I didn't really remember it. You're at the age now where your youngest fans probably have some funny ideas about the era that you grew up in. What do the teens at your shows think of "Teenage Dirtbag"?

They love this song. It may seem like an antiquated song to them — but you know, "Don't Stop Believin,' " every college kid will sing that song for the rest of history. It circles back to what you might consider contemporary folk music, like passed-around songs.

I grew up raised heavy on Jackson Browne. Then my brother introduced me to Nirvana, and my sister introduced me to Dashboard [Confessional], which led into The Used and Saves the Day. Blink really opened it up for me — I think Blink-182 has some of the best melodies ever written, just a treasure trove of almost Mother Goose-style melodies that stay with you for a long time. And then slowly, through Johnny Cash I went to the Carter family, which led to Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly, and just [realizing] how kind of punk folk music was, especially during the labor movements and stuff at the turn of the 20th century. The Carter Family put it the best: They were singing about their lives, and they had this scrutiny on expressing the hard art of living — however that looks. Whether you're a teenager in the suburbs, or you're a farmer, or you're a drug addict in Seattle, it doesn't really matter. All of those things kind of connect.

Besides your own and the original, do you have a favorite version of this song?

I heard Phoebe Bridgers do a version of it a long time ago, I think on her SoundCloud; we had the same manager at the time. That was one of the first songs that I heard her do, and I was like, "Well, damn. That's the vibe." Doing covers where there's an emotional element, and almost a darkness, infused into songs that have a really heavy tongue-in-cheek side — that's something I'd been doing for a while. So I really connected with her version.

In your own music, you've written a lot about self-destructive habits. I don't want to generalize, but I feel like a lot of the emo-adjacent music from the era in which you and I both grew up really celebrated being a mess. There's something validating in that, of course, and it can be important for a young person to hear.

There's definitely a comfort to that sort of sadness, yeah.

But it can also feel a little bleak — like a place you'll get stuck if you're not careful. What I like about a project like Dirt Emo, about the songs you chose and the way you play them, is it's a reminder that feeling your feelings at the loudest possible volume doesn't have to mean hurting yourself.

Yeah, no, those are destructive forces. And the thing about that kind of music, that comes from a real formidable sense of pain or suffering, is that giving in to that should be a constructive force. "OK, I'm admitting how destructive these things are, and I'm sad," but it stops there, and you maintain your attitude about yourself. Because when you're suffering, you don't really know what your place is in the world — unless you feel like you can stand on top of whatever is making you suffer. And then, you use things like art to be your own hero. You use things like talking about your struggle and talking about your pain to relate to others that go through that. And if you can save yourself, that automatically is a sign to other people they can save themselves.

Wheatus is still active, though Brendan Brown is the only one left from the original lineup. Have you met or spoken with him at all?

We've connected through social media, exchanged tweets here and there. We were going to do something together that didn't pan out. But I'd love to meet him at some point.

I did actually contact Wheatus to let them know we'd be talking to you, and Brendan wrote back himself with some words about your version of the song. Here's his note:

"From my 1995 demos to March of 2000 when we finalized the recording in my mom's house, I went through many revisions. I was searching for the sound of the band, but also looking for my real voice — which turned out to be quite high. I was a little concerned at the time that what felt natural to me was perhaps inaccessible to many.

"Ruston's take on it addressed that after all these years: The voice of the song is its narrative, not limited to my initial delivery. He also sings it with a newer feeling that kinda glides beyond the darker side of my own childhood, which of course, is the setting of 'Teenage Dirtbag.' Hope from a more compassionate generation isn't something I expected the song to eventually reveal, but I'll take it, definitely."

Woo-hoo, let's go! That's good. I'll take it.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.