Section Branding

Header Content

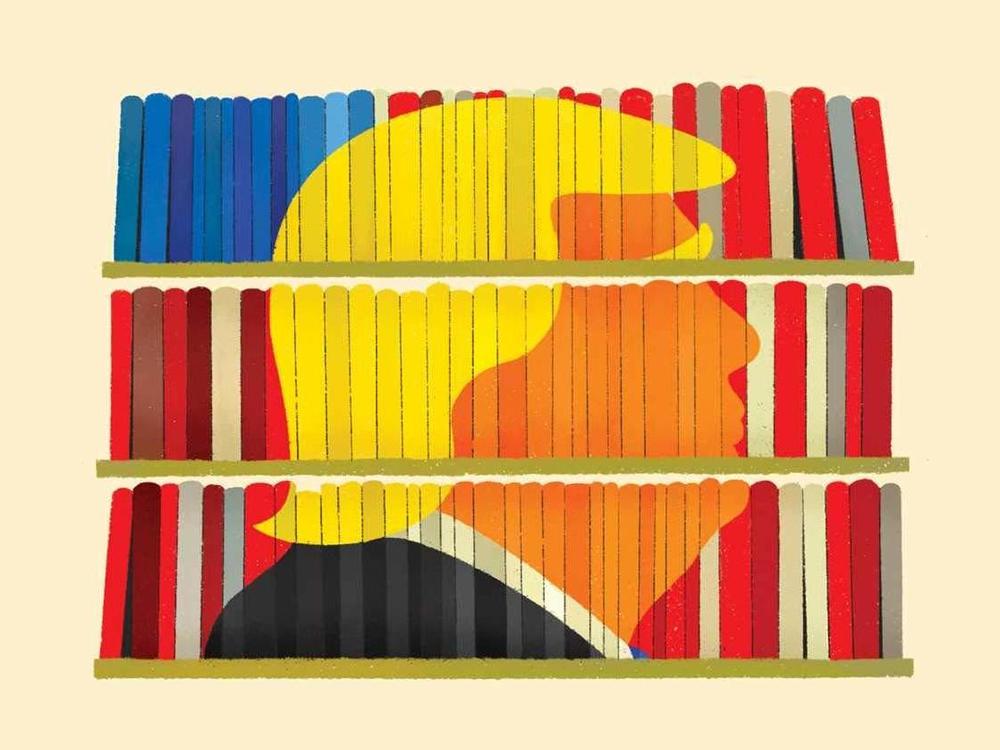

Washington Post Critic Says 'Trump Has Unwittingly Enabled' Discussions Of Race

Primary Content

As the election nears, many are thinking about how much has changed during President Trump's administration.

Carlos Lozada, a Washington Post writer who took it upon himself to read scores of books from the past four years, has some ideas on the topic. He has now written his own book called What Were We Thinking? A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era.

"I think it fits a tradition in American life. And this is a country that defines itself in writing from common sense, right? From Thomas Paine on forward. This is a country that litigates all its big battles on paper, not solely on paper, but certainly through books and writing. And this is just our turn," Lozada told NPR.

The books Lozada read, of course, include books that are all about Donald Trump. Some explore chaos in the White House. Michael Wolff wrote the first big one, Fire and Fury (and later a second called Siege), followed by others including Bob Woodward's two books Fear and Rage. Many fans of the president have written their own books, including one by the president's son Donald Trump Jr. called Triggered.

Lozada's reading list also includes a number by Americans who are far from the president trying to tell their own stories and explore their distinct American identities.

"There's a weird sense in which Trump, though, I think, has simplified all these divisions for us and overtaken them," Lozada says. "Right now, you are an anti-Trump resistance or you're a pro-Trump base, and it's almost like there's nothing else. Once Trump is gone, whether that's in three months or in four more years, once he's not this all-consuming obsessive presence, which incidentally is how he likes it, then I suspect we're going to see how those divides are really far more complicated and how, maybe, we don't line up as easily as we think we do."

Interview Highlights

On clashing identities

I think that when you look at the memoirs of the resistance, for example, you see how immediately writers started speaking solely to their own communities. It's almost like the Trump era forced everyone back into their corners. And, you know, we can worry about Trump's America, if you're in the resistance, but you really don't care much for Trump's Americans. You just are solely speaking to your distinctive community. When I see a lot of the memoirs of identity, though, I think that we see something different going on. There, it's easy to think of the identity politics movements as being all about group rights and group representation. But when you really dig into these books, what you find is just this piercing cry and call for individual dignity. And I think maybe that quest is just made easier in a group context.

On writers making a call for dignity

I would point out a couple: Patrisse Khan-Cullors is one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement — and her memoir, When They Call You A Terrorist, even though it shows the origins of this movement for the affirmation of group rights and in group representation, it really is a very individual story of her life, of her family and that quest for personal dignity that is denied her and someone like her brother who is cycling through, you know, prison and the hospital to institutions that just keep him alive enough to keep going.

Another book like that, I would say, is Ibram X. Kendi's How To Be An Anti-Racist, which got a lot of attention in the wake of the George Floyd protests. What spoke to me most about that particular book is that Kendi does not make a blanket case about the behavior or attitudes of white Americans or of Black Americans. You know, he wants to be treated on his own personal terms and he wants to treat others that way as well.

On what the past four years taught us about the prevalence of white identity politics

I think that they have just made crystal clear, as if we needed it, that White identity politics is a real thing and that it didn't just materialize, you know, through Donald Trump's sort of dog whistle politics. Of course, Trump has sort of transcended dog whistle politics. And there's a common expression in the Trump era when the president or some other figure goes beyond the dog whistle surrounding race and just says something overtly prejudiced, something that shows the underlying motivation for some political or policy act, whether it's about voting suppression or tax policy: People say, 'oh, he's saying the quiet part out loud.' And I think there's also a sense in which all of America is now saying the quiet part out loud. Groups and individuals who previously felt uncertain about speaking out are doing so. The #MeToo movement is saying the quiet part out loud. Black Lives Matter is saying the quiet part out loud. And that's a good, positive thing. I think it's ironic that a president with such a negative force for race relations in America [and] has shown such willingness to denigrate women, has presided over a period in which both groups have felt more empowered to forthrightly speak out and give their own testimony.

On people are talking about race more

It's essential that people are talking about it more. That doesn't mean that the way we're thinking about it right now means that we're getting it right. But I think it's important for this discussion to be out in the open. And I think that in some ways, Trump has unwittingly enabled that by being so retrograde in some of his own views and statements, he's made it almost impossible to not speak out in response. Now, you read some of these some of these books, you know, on the left or resistance books or identity books — and Trump is this constant foil and they point to Trump as having a sort of broken moral compass. And you can make that argument. That argument is necessarily mean that your moral compass necessarily points north at all times. I think that we can't let sort of the backlash against Trump himself and whatever his particular attitudes are dictate the way forward. But it's at least the starting point of a conversation.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content