Section Branding

Header Content

Montage Of A Dream Deferred

Primary Content

Rodney Carmichael and Sidney Madden are the hosts of Louder Than A Riot, a new podcast from NPR Music that investigates the interconnected rise of hip-hop and mass incarceration in America.

The drive upstate from Brooklyn to Dannemora, N.Y., takes about five hours, and the first thing you notice when you get there is that one structure seems to be the center of gravity for the entire town. There are scattered houses, a few car dealerships — and then, the imposing gray walls of Clinton Correctional Facility, shooting 60 feet into the sky.

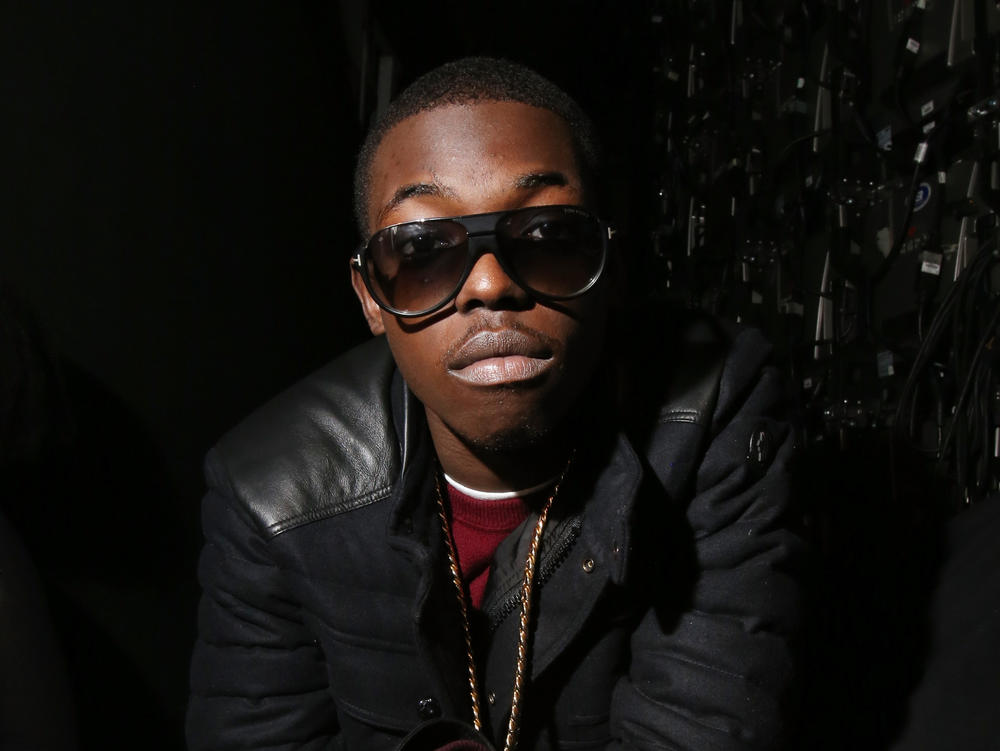

This is where Brooklyn rapper Bobby Shmurda is serving out the end of his seven-year prison sentence. Now 26, he's been incarcerated since late 2014, when he and more than a dozen members of his entourage were arrested in an NYPD raid during the recording of his debut album. In September, his parole was denied — so instead of coming home this December as fans had hoped, he'll get out in December 2021 and spend five years on supervised release.

The version of Bobby Shmurda most people know best is the one who owned the summer of 2014: the 19-year-old star of the music video "Hot N****" (or "Hot Boy," as it became known for radio), who sparked a viral dance craze, who seemed to throw his Knicks hat so high in the air that it never came down, and who turned his charisma and hood credibility into a deal with Epic Records. But that's only one side of his story. Before he got Internet famous, Bobby was "Chewy" to his boys in GS9, a crew of childhood friends raised in a part of Brooklyn that's home to Carribean immigrants and a long-brewing gang rivalry. Later, in the eyes of the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York, the only name that mattered was his government one, Ackquille Pollard.

As the months count down to Bobby leaving prison next year, hype is already building for his potential return to music — casting his abbreviated career in a new light, and bringing some old questions back into view. What drew a label as big as Epic to a teenager who had only a few songs to his name at the time? How did Bobby and his friends get on the NYPD's radar to begin with? And when the dust settled and 15 people were in prison, who else paid a price in the communities they left behind?

In the story that follows, you'll hear from people on all sides of this saga, from prosecutors to fellow rappers to Bobby himself, whom NPR interviewed on-site at Clinton Correctional in 2018. But in the end, how you view the story of Bobby Shmurda depends on how you view the overlapping worlds he has tried to move through — a major entertainment company, a rough neighborhood and the carceral state — each of whose notions of the value of authenticity sit in conflict with the others.

Debates around America's criminal justice system often hinge on a binary idea of guilt and innocence, but that framework fails to take into account how and why Black Americans are disproportionately profiled, prosecuted and imprisoned. In this country, the people policed the hardest look a lot like Bobby, and come from communities like his: places where gangs replace broken families, teenagers quit school to chase dopeboy dreams and almost everybody learns not to trust the cops. For a small percentage, rap can be a way out — but artists have to walk a tightrope to transition from the streets to superstardom.

For now, Bobby Shmurda's future is up in the air. "When you get locked up, all the rap s*** go out the window," he told us during our visit. "Right now I'm in jail. I'm just trying to get home, thinking about my freedom."

Part I:

The Industry

The myth of Bobby Shmurda has its roots in institutions across New York, but it spread, as many myths do, by word of mouth — specifically, with a phone call.

As the head of A&R for Epic Records, Sha Money XL was in the business of scouting and grooming new talent. He'd been at it a while, with previous stints at Def Jam and as the president of G-Unit Records under Interscope. One day in early 2014, he says, another A&R called him with an urgent request to watch a video that had been recently posted to YouTube.

"He was like, 'There's some Jamaican, Haitian kids in Brooklyn doing some s*** that you need to know about. I know you know what to do with this.' I was in the midst of just trying to find stars, and there was nothing I could see that was going on in New York. It was a bunch of average people trying to do it — nobody outstanding, nobody exceptional," Sha says.

He put his headphones on, clicked play, and was blown away.

The "Hot N****" video is just Bobby and his GS9 crew mobbing on a Brooklyn street corner, having fun. It's catchy, playful, clearly shot for next to nothing. Unless you listen close, you might miss what they're rapping about: selling crack, repping their set, even taking out their rivals:

F*** with us and then we tweaking, ho

Run up on that n****, get to squeezing, ho

Everybody catching bullet holes

As menacing as they're trying to be, Bobby's got this baby face that makes it hard to believe he's anything close to gangsta. The clip's real magic is the moment near the end when the rapper, holding his New York Knicks fitted by the brim, casually tosses it in the air, then briefly turns into a drunk uncle at the barbecue — hitting the hip-bopping, knee-jerking "Shmoney Dance" that would become a viral sensation all its own. The hat never falls back into the frame.

The video only had a few thousand views at the time, but Sha could already sense a buzz building. A decade earlier, he'd felt the same gritty energy radiating off a young 50 Cent, whom he'd helped develop into a household name. But by the 2010s, the epicenter of rap had shifted to the South, while the birthplace of the form was pretty much coasting in last place.

"When I seen Bobby, man, I was like, 'That's New York right there. This is what I'm looking for,'" Sha says. "To see the energy coming from my city, seeing Brooklyn, seeing the hood, hearing the song, hearing the s*** he was talking about — and then all of a sudden a hat goes off? The dance? This kid is a star, man."

Bobby had street cred, too. Sha didn't know exactly what GS9 was into, and he wasn't asking. "I know in hip-hop, the badder the better," he says. "I'm not no human resource department. I'm not a social worker. I don't ask people from the hood if they got criminal activity going on, or priors." Sha knew Bobby's rep might help sell records, but he says he also sincerely wanted to give him a better opportunity than the streets.

Anxious to sign the artist before another label snatched him up, Sha set up an audition with his boss L.A. Reid, Epic's CEO at the time. In cell phone footage from that day, you can see Bobby's wild, energetic performance play out before a couple dozen staffers crowded onto one side of a conference table at Epic's Manhattan headquarters. "That boy gave a performance like this is his last chance to do anything in life," Sha recalls.

The audition became almost as famous as the "Hot N****" video itself. It also raised some eyebrows: Here you had a black man dancing on a table, shooting finger guns, in a boardroom filled with mostly white faces — some smiling, others wearing frozen expressions, perhaps unsure how to react. But Bobby's record deal was signed before the night was over. "He was a millionaire, baby. Nineteen years old," Sha remembers. "What more can you ask for, man?"

For the next few months, Bobby was everywhere. He performed on The Tonight Show. Drake brought him onstage at the BET Awards. In September, a "Hot N****" remix dropped with features from Jadakiss, Fabolous, Chris Brown and Busta Rhymes. And when he wasn't on the road, he was in the studio. With a full-length album due soon, music was now his main hustle, and it looked like he was starting to put some distance between himself and the streets.

In at least one respect, though, he brought the block with him. GS9 was Bobby's entourage, and a few members even co-wrote his songs, but they were also his security: They moved when he moved, and they tended to be strapped. Sha says he respected that Bobby was trying to bring his crew in on the business, but that the price of that loyalty was unwanted attention from the police. Bobby spotted cops he knew from Brooklyn when he taped his Fallon performance in Manhattan, and started to see a police presence at out-of-state appearances as well.

Hoping a change of scenery would help him focus, Sha brought Bobby to L.A. to record. It didn't last. "It was so hard to get him in the studio — like, Yo, bro, leave the f****** house. Let's go. It just didn't work. But when we got back to New York, he works."

It wasn't the only time a mentor struggled to keep the artist on track. About a week before Bobby signed to Epic, his uncle Debo called a meeting in East Flatbush. He made the case to GS9 that if they really wanted to help Bobby, they needed to back off — that the heat they were drawing was going to kill his career before it started. That didn't take either. In our interview, Bobby himself admitted he didn't want to be babied.

"I had a listening problem when I was young," he says. "I listen to what I want to listen to — not to mommy, not to uncle. If you tell me the stove is hot, I wanna find out how hot it is."

There was even someone Bobby looked up to in the music industry, someone who knew his reputation, who tried to give him some guidance. The rapper Maino was Brooklyn-born and raised, and had some major run-ins with the law before he launched his career off appearances on street DVDs that Bobby had grown up watching.

"I used to pull up to a block in Flatbush, and it would always be these young kids on the block. They'd be like, Yo, what up Maino? And I would stop and talk to them," he says.

Years later during Bobby's 2014 ascent, Maino ran into him at the studios of Hot 97 and realized he'd been one of those East Flatbush kids. He says he tried to tell Bobby to avoid the drama he'd gotten tangled up in. "He was in the street longer than he was famous — so I understand. It is what it is," he says. "I tried to give them as much advice as I could about the journey, because music is supposed to be a way out for us."

Even if East Flatbush was a bad element in some ways, it was Bobby's element: His neighborhood had inspired his music, and his music is what attracted the industry to him in the first place. That volatile combination was all about to come to a head.

On the night of Dec. 16, 2014, Sha stopped by Quad Studios in midtown Manhattan, where Bobby was in a session. He was feeling good about the first part of his plan — to sell the rapper's outlaw image and connection to the streets. But his other priority, to lift Bobby out of the hood and set him on the right path, felt a little shakier.

Inside, Sha found GS9 in full celebration mode. The studio, with its pool table and sprawling city views, was only a few miles from the Brooklyn corners they'd been hustling on six months earlier, but it felt like a world away in terms of lifestyle. After shaking about 15 other hands on his way in the door, Sha made his way to Bobby, who was excited to see him and played him the highlights of what they'd tracked so far.

Late that evening, Bobby got ready to leave for the night, and Sha offered to walk him to his car. On the elevator ride down, a rare chance for them to be alone, he tried again to make his case that Bobby needed to lay low and keep his hands clean of any illegal activity.

As if to underline the point, when the doors opened, they found Busta Rhymes waiting to get on. Even Busta had heard about Bobby and GS9's reputation — an indication of how much the streets, and the industry, had been talking. They only interacted for a second, but Sha says the elder statesman gave the new kid the same advice he had, "to just chill out. You need to. This is too much right now." Then, Sha says, he walked Bobby to the front door and headed back to the studio.

Upstairs, the mood was light: blunts lit, bottles flowing. It was getting past midnight when, out of nowhere, the spell was broken.

"One of the little homies run in," Sha recalls. "Yo, they just arrested such and such downstairs! He tried to leave the building, they chased him. Yo, look, look, look! And then you see a whole bus, a police bus, pull up on a side street. Yo, look at this bus! You see nothing but police coming off this bus, like an army of them. I go, 'What the f*** is going on?' "

Within a few moments, cops were swarming the studio. Sha says everyone was panicking. "You had n****s hiding behind f****** consoles, hiding in the ceiling. Everybody was scared — people thinking about their parole."

The police spent all night searching the studio for the GS9 members they were after, finally collaring the last one around 7 a.m, and also found multiple weapons. Even though Sha wasn't on their list, he spent a lot of the night in handcuffs before being let go. At one point came a question he wasn't expecting.

"This [officer] says, 'So you're the guy that signed Bobby Shmurda?' I said, 'Yeah, why? What's up?' He has an MCM bag, and he puts it on the pool table. 'What if I make all these guns yours, so you can go to jail and not have to sign no more of these motherf*****s. Because you're signing them, and you're letting them buy these guns, and they're going back in their neighborhoods and they're shooting people. So you're the problem.' "

The officers told him that Bobby, too, was in custody. "He's like, 'We already got Bobby, and we already found weapons in his car. We got this many right here; we're going to find more. So get ready to say goodbye to your investment."

The NYPD called a press conference a few hours later. Next to a table full of guns confiscated from GS9, police commissioner Bill Bratton took the podium.

"These gang members have shown no respect for the lives of those in the Brooklyn neighborhoods where they wreak havoc," Bratton proclaimed. "But working together with the special narcotics prosecutor, we put an end to that. They shouldn't be celebrated. And the fact that their music is celebrated, and the so-called dance that they created — I would hope that those that emulate it understand what the source of it is: mindless thugs who have no conception of the value of life, no conception of morals."

Fifteen members of GS9 were arrested, including Bobby and his brother Javase, nicknamed Fame, and rappers Rowdy Rebel and Fetty Luciano. The alleged crimes varied, but everyone in the group was charged with conspiracy — which made every member ostensibly complicit in the worst crimes any of them were accused of, including murder. If GS9 was a family, the police had used that same loyalty to build the case against them.

Sha says it was critical to get Bobby out on bail. Back when he worked with 50 Cent, he was one of the bigwigs running G-Unit Records, and was used to bailing out guys on his roster. But he'd only overseen Bobby Shmurda's signing — he didn't have the keys to Epic's bank. And unfortunately, prosecutors had pegged Bobby as the big fish in their case: While most of those arrested had bail set around $500,000 or less, Bobby was looking at $2 million. "His bail is five times my salary," Sha says. "He's not my artist. I just signed him. I just work here. So what am I going to do?"

Sha was hopeful that Epic would step in and at least try to protect its investment, but that hope quickly waned. Now that Bobby's authenticity and crew loyalty had gotten him caught up in the law, it seemed the label didn't have his back. In a rare statement about Bobby on the podcast Rap Radar in 2015, Sha's boss L.A Reid basically said as much.

"When I heard him, I believed him. That's what sold me. It felt soulful. It didn't feel like someone was play-acting, it felt really believable. And I guess it was," Reid said. He admitted it had been a business decision not to bail Bobby out, that it just didn't make financial sense. "Bobby Shmurda is not the same as Snoop Dogg and 'Murder Was the Case,' who's coming off The Chronic and his first album," he said. It's a different era, you know? And we're a publicly held corporation. We just aren't in the same position we were in back in those days."

But for Sha Money, this wasn't just a business transaction: He felt responsible for Bobby, who was now behind bars on his watch. Later in 2015, Sha says, he was let go by Epic. The whole experience changed his views on major labels forever.

"So I ain't have a job ... but I don't want a job no more," he says. "What I'm gonna do? Sign another artist to a label and tell them 'We got you,' and we don't? I don't want to do that anymore. The label ain't even got my back, how the f*** I'ma tell artists I've got your back?"

NPR reached out to Epic Records for comment on Sha's exit from the company; they declined. Sha says he hasn't heard from L.A. Reid since. He doesn't blame him, but he's never worked directly for a major label since then, instead going back to his independent grind.

As for his relationship with Bobby, they kept in touch. But there was no way Sha could protect the young artist from what he was about to go through.

Part II:

The Neighborhood

Outside Spunky Fish-N-Things, a takeout spot co-owned by Bobby's mother, Leslie Pollard, the character of East Flatbush is on full display. There is soca music playing, the smell of smoke pits outside jerk joints, school kids in uniforms running off the 2 train. The neighborhood has been full of Caribbean immigrants for decades. But it's not the easiest place to grow up.

On average, the incarceration rate in East Flatbush is 33% higher than in the city as a whole, and nearly 40% of households are led by single mothers like Leslie, who grew up in the same part of Brooklyn where she raised her sons. Bobby was just a baby when his father was sentenced to life in prison, leaving Leslie to act as the glue of the family. She still calls him by the name she gave him.

"You know, the thing about single mothers is, when the father is absent, you tend to go extra to give them what they want. Ackquille really knows that it's wrong for me to do it, but he doesn't understand what 'no' means. I'm always catering to them," she says.

Even growing up, Leslie says, Bobby could be a handful. He acted out in school, when he bothered to go. But he never lacked ambition: "If I would give them five dollars a day, Javase would take his five dollars and go buy Chinese food. Ackquille would take his five dollars, go to Rite Aid and get a case of water, and sell it for $24. He was always a hustler like that."

Bobby's hustle took a turn early on, one reflected in a line from "Hot N****": "I been selling crack since like the fifth grade." He says he chose dealing drugs from what felt like a limited set of options. "Where I was from, it was like an empire. There's crackheads everywhere. It was fast money. I wasn't into robbing people." But fast money had its price. He remembers the first time he got hemmed up by the police, at age 12. "They came in the Chinese store and pulled my pants down all the way to my ankles," he says. "They found a piece of crack and they locked me up. Ever since that day, every time they see me, they just run down on me."

He also told us a story about cops planting a gun on him once. The police report claims it happened differently — that they responded to a noise complaint and saw him "showing a loaded automatic pistol" to someone else. NPR couldn't verify either version of that event, but the experiences Bobby says he's had with local police overall are far from unique. East Flatbush falls under the jurisdiction of the NYPD's 67th precinct, where the Brooklyn DA investigated at least six cases between 2008 and 2014 in which cops were suspected of planting guns at crime scenes and on suspects. The cases typically involved the same officers, a lack of forensic evidence, and some sketchy informants. (In 2016, The Village Voice reported that the investigations had quietly concluded, and the suspected officers remained on the force.)

Bobby got on local cops' radar as a preteen and stayed there. But while law enforcement saw him as a potential menace, those who knew him best saw he had something else: star potential. "Ackquille has it. He has it," Leslie says. "If you would go to a party, and someone else at the party that feels like they can dance, then Ackquille would literally dance until he passes out." The only thing missing was an outlet for his talent. That's where his crew came in.

At 17, just home from a stint in juvenile detention, Bobby found his friends getting into something new: music. Though he wasn't interested at first, he wound up getting dragged along to sessions. "Everybody kept telling me, 'Yo, Bobby, go to the studio! But I was getting money — I didn't want to go to the studio," he says. "They would abduct me. I would go with them for a little, end up making a couple songs."

The new collective needed a name, and settled on GS9 — a nod to their neighborhood set, the G Stone Crips, and the fact that they came from the 90s blocks of East Flatbush. On "Hot N****," Bobby introduces listeners to the group, touting the nicknames they created for themselves:

I'm with Trigger, I'm with Rasha, I'm with A-Rod

Broad daylight and we gon' let them things bark

Tell them n****s free Meeshie, ho

Someway, free Breezy, ho

And tell my n****s, Shmurda teaming, ho

Mitch caught a body 'bout a week ago

"They not my friends, they my brothers," Bobby says. "We jumped in front of guns for each other, all types of s***. That's just how we grew up: One of us goes, we all going."

On our second visit to Brooklyn, we met up with Fame, who was then fresh out of prison, as well as Fetty Luciano and a half dozen other guys from the crew. They explained that beefs with other crews were an everyday hazard in their world, continuations of conflicts that went back years. One of them is right there the the first few lines of "Hot N****":

Like I talk to Shyste when I shot n****s

Like you seen him twirl, then he drop, n****

Tyrief Gary, known around the way as Shyste Kokane, was the former leader of the G Stone Crips. Shyste was murdered in 2011 at age 18, shot during a Labor Day cookout in Brooklyn. The word on the street was that he was hit by a member of the crew BMW, or Brooklyn's Most Wanted.

"That put a big dent in the neighborhood," Fetty says. "Like, he's the person that brought everybody together." Fame chimes in, "We got a lot of love for each other, so when we lose one, it's bad. That's our captain right there. We ain't never let his name die out."

Bobby, Fetty and Fame were just kids when Shyste got killed, but that didn't stop them from becoming soldiers in what would turn into a years-long battle between the G Stone Crips in the 90s blocks and BMW in the 50s. When GS9's musical endeavors started to get real attention, songs like "Hot N****" played double duty — a party starter and a warning shot:

Grimy savage, that's who we are

Grimy shooters dressed in G-Star

GS9, I go so hard

But GS for my Gun Squad

But when the music video took off, Bobby Shmurda skyrocketed into a new context, way beyond hood famous. He told us about one moment that spring when he knew his life had changed. "One day we was on the block on 95th and Clarkson. I was going to make a sale, and I seen a car pull up on me — and it was a bunch of girls, around my age. They started screaming and pointing at me like, Do the dance, do the dance!" he says. "After a while, everywhere I went people was just going crazy — all these pictures, this and that. I said, 'I'll probably make some money off of this.' "

"Hot N****" took Bobby's budding music career stratospheric, and sold GS9 to the world as callous, invincible and cool. But to really understand the trouble the crew was caught up in, and caused, you have to look at what the camera doesn't show.

"I didn't really have a problem raising my kids in Brooklyn," says Rudelsia Mckenzie. "Where we were, we knew everybody. Everybody knew everybody."

Rudelsia is a 46-year-old healthcare administrator and, until a few years ago, a longtime resident of East Flatbush. But in the summer of 2012, two years before the Shmoney Dance took over New York, she started to see a problem: Her 18-year-old son, Bryan Antoine, was acting distant. "If something was really bothering him, it's like you would have to pry it out of him. He would never be home, and when he was, he was just to himself."

Not long before that unease settled in, things had been looking much brighter. Mariah Griffith met Bryan 2011, after the two connected on the event page of a party they'd both been invited to. By the time they met in person, she could tell he really liked her. "I remember he came up to me, he hugged me like he knew me forever. We stayed together in that party the whole time," Mariah says. "He was just sweet. I don't know how to explain it — he just made me feel so mushy. It was cute."

Mariah and Bryan dated for a year. In photos from that time, they hold each other close and walk hand in hand. She says she knew a lot of guys from her neighborhood who would walk around trying to act tough, but Bryan was cool with everybody — the life of the party, friends with the whole block. He would confess deep feelings to her, like the hurt he carried from his father remarrying and falling out of touch. Mariah and Rudelsia, who were interviewed together for this story, became close during that time too. "It's like my second mom — like, anything major go that goes on in my life, she knows about it," Mariah says of their relationship now.

When Bryan wasn't hanging with Mariah, he was playing basketball — at the park during the week, in tournaments on weekends, recording videos of himself at the community courts and posting them online, in hopes of one day making it to the NBA. "He always used to say, 'Mom, I'm going to be the next LeBron. I'm going to take care of you,' " Rudelsia remembers.

Bryan didn't wind up finishing high school. He began working on his GED, got a job at Jamba Juice and kept playing ball, but that's around the time Ruldesia says his optimism started to fade, especially once Mariah left Brooklyn to go to college in Washington, D.C.

I just thought maybe he was sad because things wasn't going the way he wanted it to go," Rudelsia remembers. "He probably felt deserted — like, my dad left me, now my girl leaving me?" She tried to brush it all off as growing pains. Then, on the night of Feb. 8, 2013, her worst fear came true.

That evening when she got home from work, a little after 8 p.m., Bryan wasn't there. She was just about to get in the shower when she heard a knock on the door. The knocking quickly turned to pounding, and she opened the door to find two of her neighbors looking agitated.

"They was like, 'You gotta come outside quick. Something happened to Bryan. I think he got shot.' "

Rudelsia put her clothes on and ran outside, sloshing through eight inches of snow. She came to a stop at a bodega at 830 Clarkson Avenue near East 51st Street, just steps from their apartment. Bryan was in an ambulance, a gunshot wound in his back.

"I approached the ambulance screaming and stuff, and I saw him laying there on the stretcher," she says. "The cop was trying to talk to me, you know, trying to keep my mind sane. He was saying, 'Don't worry. Your son is going to be okay. They're taking him to Kings County because they're good with gunshot victims.' "

When she arrived at Kings County Hospital, she found the doctor who'd worked on Bryan taking off his gloves. "So I said, 'Where's my son? How's my son?' He was like, 'I'm sorry to tell you, but he didn't make it.' So then I was screaming and carrying on."

She asked to see him. The doctors led her to a room. "That's when I saw him laying on the table," she says. "And I didn't even get to say goodbye."

Mariah was at college in D.C. when she got the call. "I just remember waking up the next morning in a panic, trying to get back to New York, and I couldn't even go anywhere 'cause of the snow," she says.

Rudelsia remembers clearly the last interaction had with her son. The morning before the shooting, she'd been getting ready for work and noticed Bryan getting dressed to go out too. "I said, where are you going?" she says. He was like, 'I gotta go outside, I gotta cash my check' and stuff like that. I said, do you ever just take a moment and just stay in the house? Why are you always on the go? He's like, 'Mom, I got things to do.'

"Those words that I said to him, I play over and over," Rudelsia says. "If he would have just listened to me and stayed in the house, I think maybe he would still be here."

Bryan's funeral was packed: The crowd filled the main floor of the funeral home and spilled into overflow seating outside. Rudelsia says it was amazing to realize how many people he knew, and knew him. But it's also how she learned more about the circumstances of Bryan's killing.

At the funeral, people told her that Bryan had been hanging out that night with someone she didn't know, who wasn't one of his close friends, and who might have been a member of Brooklyn's Most Wanted. And in the coming days, as folks from the neighborhood stopped by the house in the coming weeks to offer condolences, more and more hinted that they knew who was responsible for the shooting.

"It was like, "He goes by the name of Rasha.' I said, that's all you have? 'Yeah, we just know that that's the name that he go by,' and that he was bragging in the streets about how he caught a body and all this kind of nonsense," Rudelsia says. "I didn't even know what that meant."

Back in 2013, "Hot N****," the song in which Bobby shouts out his GS9 roll call — including Rasha — hadn't even been uploaded to YouTube yet. Bobby Shmurda wasn't a household name, and his lyrics weren't yet being sung by girls hanging out of cars or celebrities online. "Rasha" was all Rudelsia had to go on.

She says she contacted the detective working the case over and over for updates, and heard nothing. She was close to giving up when, a year and 10 months later, she got a call — and learned that Rasha, real name Rashid Derissant, was among the 15 people arrested in the Quad Studios raid. Police had been watching him and the rest of GS9 for months, working to build a bigger case.

On March 1, 2016, over a year after the raid, Rasha stood stood trial for a host of charges, including second degree murder. His co-defendant was Alex Crandon, a.k.a. A-Rod, who was accused of being Rasha's lookout during the bodega shooting.

The story prosecutors laid out unfolds in two parts. On Jan. 29, 2013, they said, Bobby Shmurda, Rasha and A-Rod were outside the Kings County Courthouse in Downtown Brooklyn, planning to pull up on a member of BMW named Leonel Smith. Leonel was coming from a trial, so they knew he wouldn't have a gun on him. Shots were fired right outside the courthouse, but no one was hurt and police couldn't prove who the shooter was. A little over a week later, on Feb. 8, Rasha and A-Rod walked into Star 1 Deli on Clarkson Avenue, apparently looking for Leonel again. Instead of hitting Leonel, Rasha shot Bryan in the back.

Prosecutors used video footage from the bodega's security camera to identify Rasha as the shooter. But they also presented a trove of evidence to show Bryan's murder wasn't an isolated incident: hours of recorded phone calls between members of GS9.

In the selection of calls NPR was permitted to review, guys from the crew call a GS9 member named Slice who was already serving time and update him on what's happening outside, including some shootings. Rasha and A-Rod are on a lot of the calls, and you can hear Bobby on some of them, too, which the prosecution later used to include him in the larger conspiracy case. We don't have all the calls, so it's unclear if Bobby was involved in Bryan's shooting — and in some conversations Bobby he seems to pull away from what they're talking about. He says he's too busy making money from his music to get involved, and he warns against revealing too much on the line.

If anything is clear, it's that they do not sound like organized criminals. In one call, A-Rod describes how Rasha accidentally shot a woman in the neck trying to get another BMW member, a year and a half after Bryan's shooting. In another, Slice learns that A-Rod was rushed to the hospital after Rasha accidentally shot him. They chide one another for forgetting to conceal potential evidence; they tell stories about unsuccessfully lying to the police. They are casual about the violence, but the tone is unsteady — like it could be a front for how shocked they really are.

Rudelsia came to the courtroom for the trial of Rasha And A-Rod every day, and she listened to all this evidence with mixed emotions. She kept her eyes on the two suspects the whole time. "It was hard to look at them," she says. "They're just laughing and giggling amongst each other. And that really bothered me, because they was acting like everything was just normal, like they didn't do anything wrong."

Something else bothered her. During the trial, prosecutors referred to the woman Rasha shot as an innocent victim, but Bryan didn't get that label. Instead, their argument rested on the idea that Rasha and A-Rod had a gang-related motive to kill him: that Bryan was, himself, a BMW member.

"Bryan was not in a gang," Rudelsia insists. "Bryan is not a fighter. Bryan doesn't like to start trouble. Bryan was just a sweet kid. He's not about that life. That's not him." She points out Bryan didn't have a gun on him, and that he didn't have a criminal record.

Whatever the truth of the matter, "innocent until proven guilty" didn't seem to apply to Bryan in the courtroom. Prosecutors pointed out that in the surveillance video, the guys with Bryan were visibly upset watching him die, that one broke a glass door in rage. They said since those guys were BMW, that was all the proof they needed that he was affiliated, too. Painting Bryan as a BMW member made it a lot easier for the prosecution to rationalize his murder as one of revenge — an easy narrative for a jury to understand.

We talked to people who were close to Bryan, on and off the record, who said as far as they knew he was not gang-affiliated. We also asked the prosecutor's office what evidence they had to prove Bryan was a member of BMW. They told us a detective was willing to testify in court about Bryan's affiliation, to prove that his murder was an act of gang retaliation. But because defense attorneys blocked that witness, the prosecution couldn't and wouldn't tell us anything more.

Rasha and A-Rod were each found guilty of second-degree murder and attempted murder in April 2016. Both were in their early 20s at the time. A-Rod received 49 years to life; he'll probably leave prison in his 70s and spend the rest of his life on parole. Rasha got 89 to life, meaning he's likely never coming home.

Rudelsia wrote a statement for their sentencing hearing, which read in part:

"My son's killers are still alive. And I most certainly don't wish death on them after going through this. I wouldn't wish it on any mother. But my son needs justice, and the killer should not be roaming the streets. My son will never be alive again, but Rashid Derissant and Alex Crandon will kill again, in my opinion. They have shot and killed my son in cold blood, and this action is something that they live by. My family needs justice. My son's younger brother needs justice. I need justice."

We asked if she felt justice was served in the end. "Justice, for me, is that they will have a lot of time to sit down and think about their actions," she says. "And I'll be hoping that while they're in jail, that they will see what they have done to my family, and that this would be a lesson to anyone out there that commit the same crime as they have, to not do this to another family."

Mariah says Bryan's life and death have had a lasting impact on her and her relationships, even though they were only together a year. "Nothing that these guys out here can do can break my heart, because I feel like I've already gone through like the worst with losing Bryan," she says. "Granted, we didn't have any kids or anything like that — but that was just pure love, me and him."

Reminders of what she lost are getting more frequent lately, as she's started to see social media posts anticipating Bobby's release. Mariah does like hip-hop, but her friends know to turn off "Hot N****" if it comes on.

"Even though he didn't pull the gun, he wasn't there — he's glorifying it. He's making other people think that this is okay, that you can kill someone and then turn around, put it in the song and blow up off of that. So it's not a party song for me. It's just a reminder of what they did," she says.

"If he would have at least even acknowledged it — like, 'Look, I'm sorry that this happened — maybe, you know, it could be OK. But at this point it's like, y'all are just heartless. That's how I felt, like they don't have a human bone in their body. How many went down? All these people in jail. Bryan's gone. And all you have to scream is GS9 and BMW or whatever you're repping. It's not worth it."

Rudelsia moved her family to New Jersey a few months after Bryan's death; she says didn't want to raise her youngest son in East Flatbush. Mariah became a teacher in Maryland. She doesn't go back to Brooklyn except to see family.

Part III:

The System

There's a song Bobby released in 2014, about a month before the raid at Quad Studios, called "Wipe the Case Away." If you listen to it now, it feels like a premonition:

I told my lawyer, "I got 40 on me,

Is you trying to go to court for me?"

These n****s trying to put a charge on me

Why they wanna lock the doors on me?

Why they wanna put some fraud on me?

Bobby appeared in court for the first time just hours after the raid. Prosecutors laid out a host of charges including weapons possession, reckless endangerment, conspiracy to sell narcotics and conspiracy to commit murder. They claimed GS9 and its namesake, the G Stone Crips, were one and the same.

By this point, two of Bobby's closest friends were headed for what could amount to life sentences for the murder of Bryan Antoine. From a legal standpoint, he now had two choices: face a jury trial and risk getting decades in prison, or plead guilty for a fraction of the time. But in his mind, the choice was more straightforward: to go for self, or go for crew.

When Bobby was first indicted, his first lawyer on the case was Howard Greenberg, who had previously helped him beat some weapons charges. In the 1980s, Greenberg had (unwittingly, he says) married into a mafia family, who in 1984 was implicated in the infamous "Pizza Connection." That major criminal case found that the Sicilian mob had been smuggling heroin and cocaine into the U.S. and selling it through pizzerias across the country, and led to two dozen people being tried under the RICO Act.

Short for Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, RICO was created in 1970 to take down the crime rings that had plagued cities like New York and Chicago for decades: groups like the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club or mob families like the Gambinos, organizations with hierarchy. Laws like RICO allow prosecutors to hold anyone in the enterprise responsible for the worst thing someone in their circle has done. (It's the same law that brought down DJ Drama and his mixtape business in 2007.) Thanks to a wiretap, a paper trail and witness evidence, 20 Pizza Connection conspirators were eventually convicted, including Greenberg's father-in-law and his wife's uncle.

All these years later, even if GS9 wasn't being prosecuted under the exact same law, Greenberg felt he knew how to defend Bobby successfully. His argument was to have Bobby distance himself from the crew, in order to make the conspiracy claims as flimsy as possible.

"You're not your brother's keeper," he says. "My theory about defending him [was], this kid was rich, and he was busy. He didn't have the time to get into this bulls*** with the people who are hanging around him." Greenberg never got to put his defense into action, however: According to him, he was fired out of nowhere by Epic Records.

Around this time, the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor picked up Bobby's case, moving it from the Brooklyn court system into Manhattan. It's an office with uniquely broad powers: Unlike a district attorney's office, it has citywide jurisdiction and takes cases from all five boroughs, especially drug trafficking rings. A decade or two ago, Bobby's case would never have fallen under its purview. But by 2014, arrests in New York — especially for felonies like murder and drug crimes — had all declined, leaving the office with bandwidth to spare.

"Our office's mission is to focus on the critical issues that are facing the city and their relationship to drugs," says Special Narcotics Prosecutor Bridget Brennan, who has led the office for 22 years. "This organization was involved in a spate of violent crime here in the city. Neighborhoods were terrorized. And it initiated with complaints about dealing drugs."

The "organization" Brennan is referring to here is GS9. Conspiracy laws give prosecutors, especially those as powerful as Brennan, lots of flexibility to build a case: Bringing in evidence like social media posts or phone calls to support the argument that defendants made an agreement to break the law is all fair game.

"What's important about a conspiracy charge, certainly to a jury or to a judge, is that it allows you to put people in context, so that it's not merely possessing a weapon without any kind of context of how or why," Brennan says. "It allows them more information and a better insight, so it's an important tool."

The hook of the prosecution's story was that police had caught Bobby with guns — what they described as artillery for GS9's ongoing gang war. Even though Bobby may not have been a part of the shootings of Bryan Antoine or the other bystander, according to Brennan he was still complicit in those shootings. But the argument went further than that: Bobby's name appeared at the top of the initial NYPD press release, and his bail was set much higher than those of his friends. "I think the way we characterized him was 'a driving force,' " Brennan says.

Brennan is firm that she didn't take Bobby's celebrity into account in building the case, but she points out that the crimes didn't stop when he got famous: Five GS9-related shootings happened after "Hot N****" went viral, one of them in Miami while he was there for a scheduled performance. Prosecutors pointed to the wiretapped phone calls, alleging that Bobby had talked about firing a weapon in public on some of them. They called him a "prolific" drug dealer. They argued that he was making money off music and flipping it to fund the beef. If the prosecution was treating GS9 like the mafia, Bobby was being painted as the kingpin.

We asked Brennan if prosecutors ever take into account the overarching circumstances that contribute to people like Bobby living this type of life — or if they see long prison sentences for young black men as the only solution to this problem.

"Well, of course we think about what can be bigger, broader solutions. You also have to keep in mind that this neighborhood, all the neighborhoods in our city, are full of people who struggle," Brennan says. "This kind of behavior is very rare behavior. A lot of people have it tough, and they manage to live their lives peacefully, lawfully — and they are victimized by gang violence. So the real challenge is, how do you balance all that out."

After dropping Howard Greenberg, Bobby hired attorney Kenneth Montgomery. As a kid, Montgomery had come up with a close-knit group of friends — and they kicked up a lot of dust.

"Running around acting crazy, robbing people on trains, fighting other groups of kids, robbing stores, boosting. Danger was always a second away," he says. "When you live in a concentrated neighborhood like that, you're always onstage. That affects how you're accepted by your peers. That affects how people treat you, how they look at you. That was peer pressure at its finest."

If Montgomery's youth sounds a lot like Bobby's, the difference is that he got the chance to outgrow it. He made it to college, then to law school. And his first move after passing the bar wasn't the type of defense work he's become known for; instead, he started his career as a New York City prosecutor. The plan, he says, was to be the "spook by the door" — gleaning information from the inside that could help make him a better defense attorney in the long run.

"It gave me a really close-up view to how insanely unfair the system is," he says. "[A] white supervisor, he sees the kid with an East New York, Brownsville address, and he makes racist assumptions about that kid and what his crime is, or what his bail should be. It's not a mistake that we have 2.5 million people in jail and the majority of them look like that. You want apples, you go to an apple orchard. You want defendants, you go to Black and Hispanic neighborhoods."

When Montgomery took Bobby's case, he saw it as an extension of all of those problems. He thought the charges were overblown — that there was no sense comparing GS9 to the mafia, that the link between Bobby and the murders was thin at best.

"A group of kids growing up in an oppressed neighborhood with no organization, no structure, no pattern, no suppliers, making no money? That's not an enterprise," he says. "The conspiracy to commit murder was weak, because they cannot point to anything that can say Ackquille Pollard was instrumental in someone being shot and killed. They were doing that based on association."

But he understood why the prosecution would present things this way. He says prosecuting a case of this kind means creating a narrative — and that narrative would be most effective on a jury made up of people outside his community.

"You take a bunch of people from Brooklyn, and all of a sudden now they're being prosecuted in Manhattan? It changes the nature of the prosecution," he says. "A Manhattan jury, which traditionally knows nothing about the issues that happen in Brooklyn — that's not a jury of your peers."

Babe Howell, a professor of criminal law at the City University of New York and a seasoned defense attorney, has been following the policing of street crews for years. She says that even though crews don't have hierarchies or rules in the way gangs do, police and prosecutors often refer to crews as gangs, and prosecute them as organized crime outfits.

"Actual proof of membership is not needed," Howell says. "The colors you wear, the bodega you go to, your cousin, your yearbook photo: All of that can be used as evidence that someone's a gang associate or gang member. Conspiracy laws make a conspiracy incredibly easy to prosecute, nearly impossible to defend, and they carry very, very harsh penalties."

In 2016, there was a federal RICO case known as the Bronx 120, which involved a much bigger sweep than the GS9 raid: 120 people rounded up from the Bronx neighborhood Eastchester in the middle of the night by an army of police in tactical gear. Co-organized by the NYPD, DEA and Homeland Security, it was called one of the biggest "gang takedowns" in U.S. history. The district attorney at the time said the men were charged with racketeering, narcotics, illegal firearm charges and a handful of murders.

Howell says it's worth paying attention to the exact numbers. "There are eight homicides associated with that sweep," Howell says. "That's 112 who didn't do the homicides, all getting painted with a RICO conspiracy that includes murder."

According to Howell's research, most of the Bronx 120 were guilty only of misdemeanors like marijuana sales, but ended up pleading to felony charges because of RICO. The vast majority of those convicted were under 30 years old. Whether or not a defendant in such a case is ultimately proven to be a gang member has little bearing on the end result. (As a side note, a recent study showed 86% of federal RICO prosecutions involved people of color.)

Those who defend conspiracy laws argue that they can be a deterrent — a tactic to persuade young folks not to join gangs. But Howell says putting people behind bars often has the opposite effect.

"Gang membership is a transitional phase," she says. "People tend to join in adolescence. They quit a year or two later: They get a job, they have a child, they find a girlfriend, they move out and move on. It's very unusual for a gang member to stay a gang member over years or decades. But if we arrest, prosecute, and imprison at this critical moment in life, then the gang identity becomes the most important part of their life. And they're usually trapped by the criminal justice system, by the felony records, into identifying even more strongly with the gangs."

Kenneth Montgomery, who actually defended a member of the Bronx 120 himself, knew all of this, and felt that Bobby needed to avoid a trial at all costs. "A kid that age, with that much at stake, with evidence that was I'd say was probably overwhelming for the type of case that it was ... a trial would be nonsense," he says. "I told him that I think we should see what's the lowest number we can get, and get him in and out of this thing."

Avoiding trial would mean pleading guilty and seeking a deal with the least possible jail time. And to be clear, this is the way it goes for 94% of criminal defendants: Prosecutors offer them a plea deal, and they take it.

But Bobby wasn't having it. The rapper recalls his conversation with Montgomery this way: "I'm like, 'What you mean, the lowest time?' You supposed to be going to the District Attorney, [or] the Attorney General. You supposed to be doing a whole bunch of other s***."

Things got tense between them, and Montgomery felt that if he couldn't convince the rapper to take a plea there wasn't much more he could do. So Bobby, determined to have his day in court, fired him.

In the summer of 2015, Bobby hired his third lawyer, Alex Spiro, a well-known Manhattan attorney whose past clients include Jay-Z, and who is currently on staff at Roc Nation's criminal justice arm, Team Roc. According to court documents reviewed by NPR, Spiro made a number of attempts to help Bobby's case by filing motions to dismiss some evidence and throw out some of the charges, to no avail. And since Bobby had never been able to raise that $2 million bail, he was stuck behind bars the whole time he awaited trial — nearly two years, all told.

"Having an incarcerated defendant disconnects them from society. It makes it harder for them to defend themselves, harder to work with their lawyer, harder to review discovery and evidence, harder to procure witnesses on their behalf," Spiro says. "They had him in jail, and they had already taken two years from him. They were in a better bargaining position than he was."

Finally, in September 2016, the prosecution declared it was ready to begin trial for Bobby and the three GS9 co-defendants named in his case: Rowdy Rebel, Montana Flea and Cueno. Jury selection was scheduled to start in three days, and if convicted, Bobby was facing more than 50 years. To avoid trial, prosecutors offered a plea deal. But there was a catch: This was a specific arrangement called a "global" plea, wherein if one co-defendant declines the offer, none of them get it.

In court transcripts from that day, the judge asks the defendants one by one if they accept the prosecution's terms. Rowdy Rebel and Montana Flea are each offered seven years and agree to plead guilty. When the judge gets to Bobby, he offers him seven as well. Bobby hesitates for a moment, and then decides to take the deal. Cueno — who, unlike the others, has been charged with committing several non-fatal shootings — is being offered the most time: 15 years. And Cueno decides not to take the deal.

The judge says he has to, or everybody is going to trial. The lawyers approach the bench to negotiate, and in the end, Bobby, Rowdy and Montana are allowed to take the plea. Cueno, severed from the deal, goes to trial — where he's eventually sentenced to a minimum of 117 years for 23 counts including attempted murder, around eight times the original offer.

Though Bobby was originally charged with eight counts, in the end he had to plead guilty to just two crimes — one count of weapons possession and a related conspiracy charge. The other six, including conspiracy to murder, were dropped. That outcome raises a question, which we posed to Bridget Brennan: Did the prosecution have the evidence in the first place to convict Bobby of conspiracy to murder if things had gone to trial, or was that charge just a negotiation tactic?

"What difference does it make in the end?" Brennan says. "I mean, he pled guilty to charges that he agreed he was guilty of. We agree he is guilty. I'm not going to talk about the murder conspiracy, because we didn't prove that charge beyond a reasonable doubt. We wouldn't have brought it had we not thought we could prove it beyond a reasonable doubt."

But to critics of plea deals, throwing everything but the kitchen sink at a defendant to get them to plead guilty, including charges with little justification, is the bigger injustice — especially when 94% of state prosecuted cases end in a deal. Even if prosecutors ultimately withdrew the most explosive charge in Bobby's case, it still helped them secure a guilty plea.

Bobby says he only took the deal to help Rowdy and Montana avoid trial — that he would have fought for less time or gone to trial himself otherwise. The story does have one last-minute hiccup, though, and it's a part of the narrative that's rarely talked about. A month later, Bobby showed up for sentencing, alone this time. At this point his plea was already locked in, so the appearance was just a formality. But in the middle of the hearing, Bobby suddenly tried to renege on the deal.

"I want my plea back," he told the judge. "I was forced to take this plea. I don't want it."

Spiro jumped in, trying to smooth over the situation. "My client is clearly frustrated," he said. He explained that Bobby was concerned about "the way conspiracy laws work to make him responsible for his friends' actions."

"Leave me alone," Bobby told him. "I withdraw my plea and I'm firing you."

In the eyes of the court, it was too late. The judge told Bobby, "I was satisfied when I accepted your plea that your plea was voluntary." He added that this outburst was not the formal way to submit such a request. Then he handed down his sentence — a maximum of seven years.

All of these details, again, come from court transcripts; we don't know how Bobby looked or sounded as he said these words. We did ask him about that day, and his response was fairly matter-of-fact: "I wasn't going to take the plea, because I didn't feel like the evidence was good enough for me to be taking a plea."

Spiro, despite having nearly been fired in that moment, says he can understand where Bobby was coming from. "All I can say is, on something that has this much on the line, with somebody young who the system has in many ways failed? I would expect that a person would have second thoughts about it on a day-by-day basis," he says. "I mean, you never know what would have happened down road number two."

Epilogue

Late last year, we caught up with Kenneth Montgomery one more time at Brooklyn College, on the last day of the semester for his class "Blacks and the Law." After he'd finished handing out final papers and saying goodbye to students, we asked his thoughts on the bigger picture: what Bobby's story ultimately says about the link between hip-hop and mass incarceration, and what's missing from the way we talk about Black and brown men and their entanglement within these systems.

With some fatigue in his voice, Montgomery asked if we were familiar with a courtroom photo that circulated online around the time he was working Bobby's case. "It's this stupid meme that goes around — of me, Bobby and a court officer boy of mine."

In the image, Bobby is in a prison-issued sweatsuit, and his hands are cuffed behind his back. Beside him, Montgomery wears a sharp gray suit and a nice watch, arms crossed like he's contemplating his next move. Behind them, a Black law enforcement officer in uniform stands at attention. The caption says, "Three men in three different positions. In America, your color doesn't define your future. Your choices do."

"It looked like it was probably drafted by some young Proud Boy," Montgomery says. "But everybody don't have autonomous choices. Everybody got choices, but everybody don't have free, autonomous choices. Your ability to have a free and autonomous choice is impacted by the community you come from.

"I think Bobby was doing in the street what he was bred to do. White America, corporate America, saw the commodity in it. It's like America commodified black pain, black death, so efficiently and seamlessly that we don't even question it anymore."

In the years since Bobby went away, the sound of his city has changed. Chicago and U.K. drill music have migrated to New York, mixing with the West Indian flavor of the streets he grew up on. These days, Brooklyn drill is taking over: Artists like the late Pop Smoke, and even GS9-afilliated acts like Fivio Foreign and Fetty Luciano, are making waves.

A lot of the seeds of this movement trace back to the viral whirlwind Bobby co-created in 2014. It's one of the reasons why many hip-hop fans can't wait for him to come home, to see and hear what he'll do with the evolution of this sound. And in contrast to the recent homecoming of fellow Brooklyn rap star Tekashi 6ix9ine, whose legal drama ended in him testifying against his old crew, Bobby will likely be a hometown hero to those who put a premium on loyalty — the same street code that defined his image as an artist and got him in such deep trouble with the law.

Sha Money XL says he still believes Bobby's future is bright, even after all that's happened. "I want him to grow, do his thing, make all the money he didn't make plus more. Become a Jay-Z, that guy that can become an example," he says. "Don't do the wrong thing, man. Do the right thing. Stay righteous."

Maino, too, says Bobby has a chance to come back strong — and keep things that way, if he's careful. "He's gonna come home hot, so take advantage of that. Get to the bag. Get in the studio. You want to wake up and see cars in your driveway," he says. "We don't have nothing else to prove no more. It's like, how real can we keep it? How real do we want to keep it? No, it's already done. Live, man. Live."

In a sense, living is the thing Bobby Shmurda never got the chance to do. When labels prioritize your authenticity, your friends prioritize loyalty and the criminal justice system prioritizes convictions, it's hard to remember that living should be your top priority.

When we visited Bobby in 2018, it was hard not to notice right away how grown he looked, much more filled out than in the music video that introduced him to the world years ago. His smile was still bright, but there was sometimes a distant look of sadness in his eyes — especially when we asked about his case, and how prosecutors had presented him as the ringleader of a criminal enterprise.

"It was painted as, I had the money. I'm the gang leader. And the people I grew up with, they murderers and stuff. That's how they painted the picture, and people just go along with it. You know what I'm saying? Because they have a badge or something, so now they looked at like they word is golden," he says. "I'm not a criminal. ... I don't look at myself as a convict or a felon. I look at myself as a hostage right now."

Bobby has thought a lot about everything that's happened. He's read his case file, and learned more about how gun and conspiracy laws work. He says that when he gets home he'll still need security around him, but doesn't plan to carry weapons himself anymore — which is the closest he gets to admitting any wrongdoing around his conviction. He's kept an ear to the streets too, staying up to date on trends in hip-hop through tips from his friends outside. He plans to go back to rapping when he gets out. But he doesn't want to be anywhere near New York.

Near the end of our conversation, we asked what the biggest lesson he's learned is. He thought for a second. "My black ass should have started rapping since I was 10 or something," he finally said, with a quiet laugh. "I would have never been in the streets, you know what I mean? My biggest regret is not following my dreams earlier."

This story consists of material published within three episodes of the NPR Music podcast Louder Than A Riot. It includes editing and reporting by Adelina Lancianese, Dustin DeSoto, Matt Ozug, Michael May, Chenjerai Kumanyika, Jacob Ganz and Daoud Tyler-Ameen.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content