Loading...

Section Branding

Header Content

Learning a new skill can be hard. Here's how to set yourself up for success

Primary Content

This is one of my favorite questions to ask people: What was the last thing you taught yourself how to do?

I (Rommel) like it because the answers are usually less about the actual skill and more about the motivation behind learning it. It's a question I leaned on a lot when I was booking contestants on the NPR game show Ask Me Another.

But I don't really get to ask it anymore. Maybe it's because I'm in my 30s and I'm not meeting as many new people these days. The pandemic might also be a factor. Plus, Ask Me Another recently ended, and it got me thinking about my time on the show and "the question" that so often cracked people open in a really interesting way.

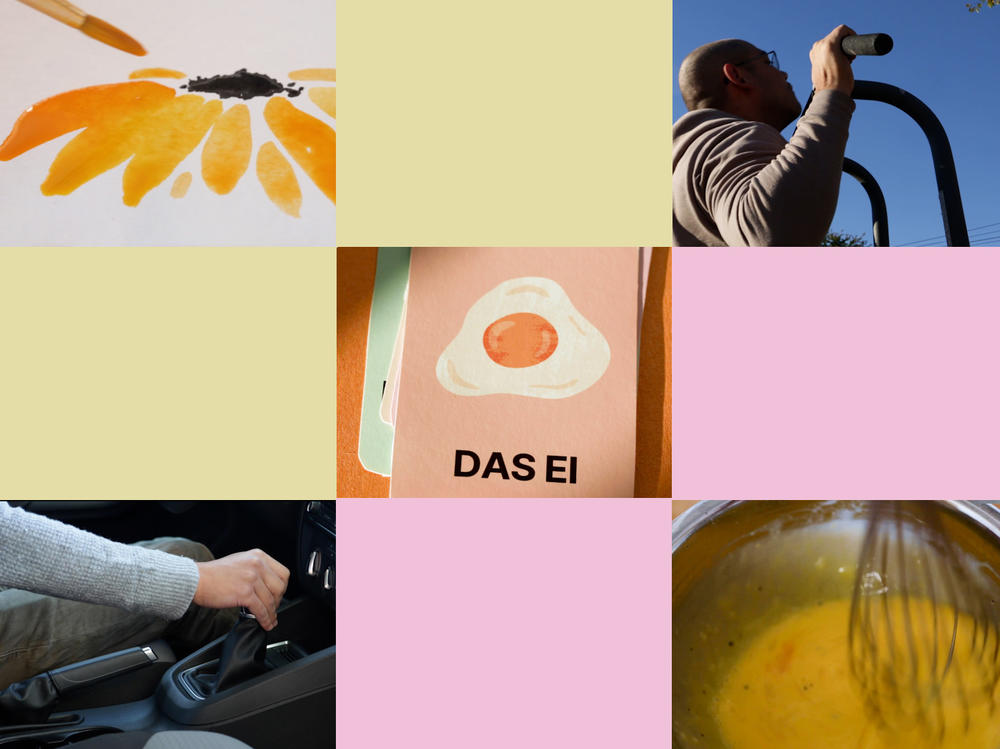

So I reached out to some former contestants to see if they remembered their answers. Sam Cappoli learned how to drive a car with a manual transmission, AKA "a stick." Amy Paull was training herself to do a pull-up. Cappoli's motivation was to finally learn how to do something his mom tried to teach him as a teenager. Paull's motivation was to gain strength so she could become a better escape room teammate. But there is more to both of their stories. Sam realized that he couldn't learn how to drive from just watching a few youtube videos and a shoulder condition made Amy re-evaluate her goal of pullup dominance.

It can be incredibly gratifying to harness mastery of a skill. But, why is learning new things so hard?

Maybe it's because we need to rethink how we go about learning. Here are some tips! Figure out what it is that you want to learn. Then...

Set yourself up for success

In addition to asking former Ask Me Another contestants "the question" I also turned to my 3-year-old daughter and asked her what was the last thing she learned how to do? She was quick to tell me she can turn on the lights all by herself. After a couple of years of attempts, she is now tall enough to reach a switch and has mastered the fine motor skills it takes to grip a switch and flip it on and off. It's a skill relevant to her but also to everyone — we just don't necessarily think of it as a skill anymore.

Rachel Wu is an associate professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside. She studies how we learn over the course of our lives. Wu says it's easier for kids and babies to learn new things because their whole lives are centered on learning. Babies are incredibly open-minded. They want to learn everything because everything is relevant to them.

Wu says we can learn from that by asking, "is the thing I'm trying to learn relevant to my life?" Next, find yourself an instructor — someone who is really good at breaking up the things you want to learn in approachable ways.

Then, give yourself a realistic timeline to learn something new. Using babies as an example — we don't expect newborns to be able to communicate the second they are born. It often takes a baby at least a year to start accumulating a pen of recognizable words in their vocabulary. Give yourself the same amount of time to learn something as you'd give a child to learn it too.

Keep tinkering with the challenge at hand

If you're struggling to stay motivated, or feel like you're hitting a wall in your progress, stop and adjust your process. Play around with your method by introducing a new path to learning.

Take Wu, for example. She's learning how to speak German. She takes classes on the campus where she works, but she also started watching one of her favorite TV shows, The Nanny, dubbed in German and slowed down to 50%.

"The Nanny was nice because it teaches you more everyday language, and phrases that you would encounter on a daily basis," Wu says.

She uses this handy trick with Pixar films and with listening to German audiobooks for kids.

Tinkering is part of it but so is accepting that you'll need to be open to possibly starting over.

Take Nell Painter. Painter is a retired professor at Princeton. She wrote a book called, Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over. When she was in her 60s she earned a bachelor's degree and an MFA in painting. She says an exercise she learned during an early art class really helped her adjust her relationship with her work and mistakes.

She would draw and draw, look at the model, and draw some more trying to get it right, Painter says. Then the teacher would come and tell her to "rub it out and draw it again, 10 inches to the right." Once again, Painter would draw and work to get it right, and then the teacher would say rub it out and draw it 10% smaller.

"The lesson is you can rub out your work," Painter says. "It doesn't all have to be a [masterpiece.] It doesn't all have to be right, and it doesn't all have to be saved. ... You can rub that sucker out."

Don't be afraid to make mistakes

We don't like making mistakes. But when you're learning something, mistakes are an important part of the process.

Manu Kapur is a professor of learning sciences and higher education at ETH in Zurich Switzerland, where he writes and teaches about the benefits of renormalizing failure and the idea of productive failure. He says the struggle to let yourself make mistakes is really hard.

"It's a constant effort to tell yourself that 'This is something I do not know. I cannot possibly expect myself to get it immediately,'" Kapur says. "when I'm struggling, I just need to tell myself that this is exactly the right zone to be in and then to do it again and again and again. And until such time, you just become comfortable with being uncomfortable because you're learning something."

So, if you're worried it's too late to start that new language class or the fear of failure has stopped you from picking up that instrument, this is your sign to put your caution aside and just get started. Failure will likely be a part of the process, and that's okay. It's the trying — and the learning — that counts most.

The audio portion of this episode was produced by Andee Tagle, with engineering support from Stuart Rushfield.

We'd love to hear from you. If you have a good life hack, leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823, or email us at LifeKit@npr.org. Your tip could appear in an upcoming episode.

If you love Life Kit and want more, subscribe to our newsletter.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.