Section Branding

Header Content

NASA is just now opening a vacuum-sealed sample it took from the moon 50 years ago

Primary Content

Fifty years ago, astronauts on one of NASA's Apollo missions hammered a pair of tubes 14 inches long into the surface of the moon. Once the tubes were filled with rocks and soil, the astronauts — Eugene Cernan and Harrison "Jack" Schmitt — vacuum-sealed one of the tubes, while the other was put in a normal, unsealed container. Both were brought back to Earth.

Now, scientists at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston are preparing to carefully open that first tube, which has remained tightly sealed all these years since that 1972 Apollo 17 mission — the last time humans set foot on the moon.

Why so long? To take advantage of the technology of the future — our present.

"The agency knew science and technology would evolve and allow scientists to study the material in new ways to address new questions in the future," says NASA's Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division.

The unsealed tube from that mission was opened in 2019. The layers of lunar soil had been preserved, and the sample offered insight into subjects like landslides in airless places.

Because the sample being opened now has been sealed, it may contain something in addition to rocks and soil: gas. The tube could contain substances known as volatiles, which evaporate at normal temperatures, such as water ice and carbon dioxide. The materials at the bottom of the tube were extremely cold at the time they were collected.

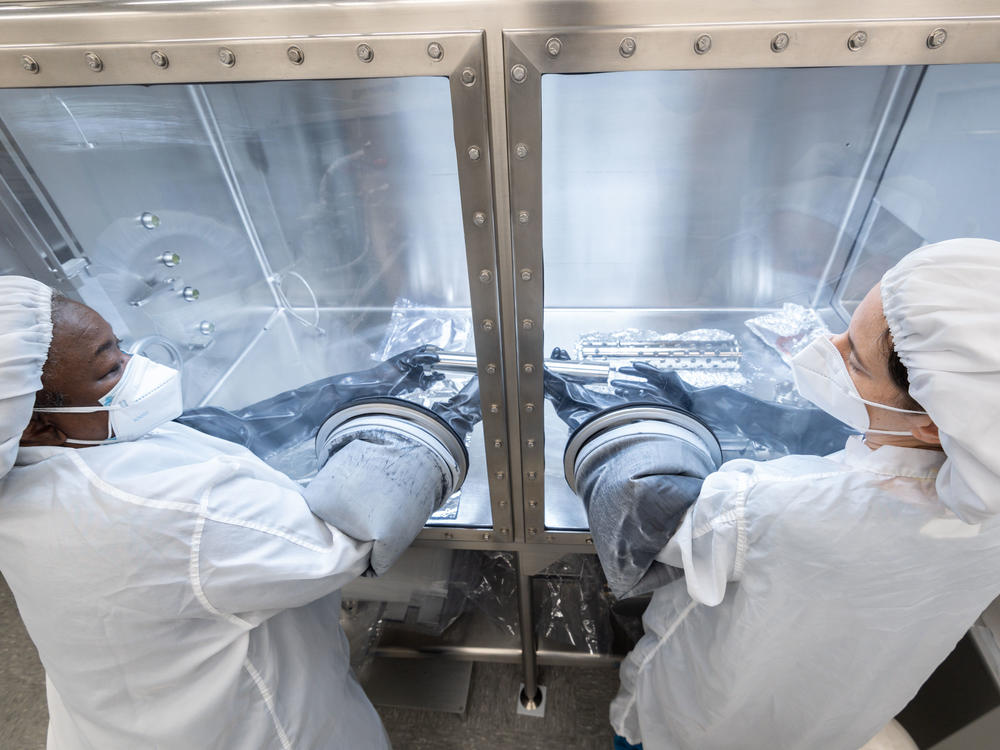

The amount of these gases in the sample is expected to be very low, so scientists are using a special device called a manifold, designed by a team at Washington University in St. Louis, to extract and collect the gas.

Another tool was developed at the European Space Agency (ESA) to pierce the sample and capture the gases as they escape. Scientists there have called that tool the "Apollo can opener."

The careful process of opening and capturing has begun, and so far, so good: the seal on the inner sample tube seems to be intact. Now, the piercing process is underway, with that special "can opener" ready to trap whatever gases might come out.

If there are gases in the sample, scientists will be able to use modern mass spectrometry technology to identify them. (Mass spectrometry is a tool for analyzing and measuring molecules.) The gas could also be divided into tiny samples for other researchers to study.

"Each gas component that is analyzed can help to tell a different part of the story about the origin and evolution of volatiles on the Moon and within the early Solar System," explained Francesca McDonald, who is leading the project at ESA.

Ryan Zeigler, the Apollo sample curator at NASA, said that 10 years after it was proposed, the project is stirring excitement. And with these two new tools, he says, there's now "the unique equipment to make it possible."

The analysis of these samples is connected to NASA's Artemis missions, which will send humans to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years. Part of the plan for Artemis is to bring a woman and a person of color to the moon's surface for the very first time.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.